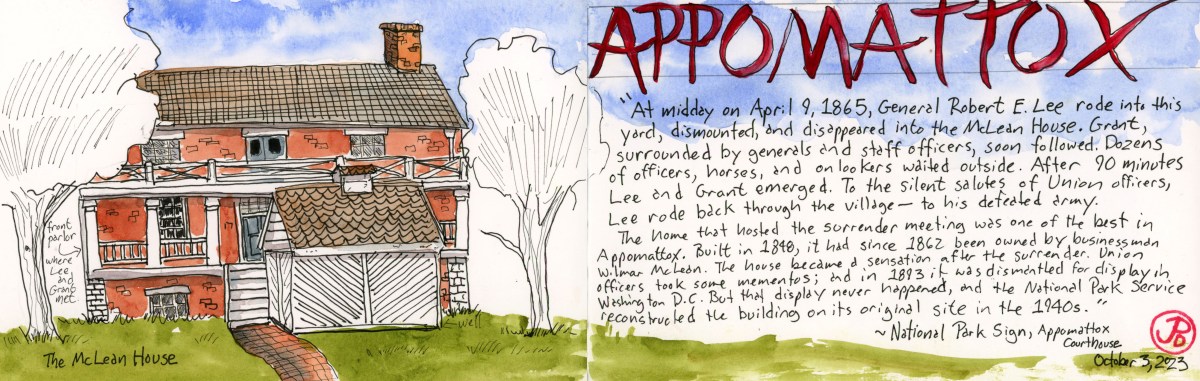

One of the most touching passages of the Civil War happen on April 12, 1865 as Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse.

The setting was northeast of the courthouse and just past the Peers House on the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road. This was the offical surrender ceremony a few days after Lee had surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at the McLean House.

The event is best related in a passage from James McPherson’s Pulitzer Prize winning history of the Civil War, Battle Cry of Freedom:

The Union officer in charge of the surrender ceremony was Joshua L. Chamberlin, the fighting professor from Bowdoin who won the medal of honor for Little Round Top, had been twice wounded since then, and was now a major general. Leading the southerners as they marched towards two of Chamberlain’s brigades standing at attention was John B. Gordon, one of Lee’s hardest fighters who now commanded Stonewall Jackson’s old corps. First in the line of march behind him was the Stonewall Brigade, five regiments containing 210 ragged survivors of four years of war. As Gordon approached at the head of these men with “his chin drooped to his breast, downhearted and dejected in appearance,” Chamberlain gave a brief order, a bugle call rang out. Instantly the Union soldiers shifted from order arms to carry arms, the salute of honor. Hearing the sound General Gordon looked up in surprise, and with sudden realization turned smartly to Chamberlain, dipped his sword in salute, and ordered his own men to carry arms. These enemies in many a bloody battle ended the war not with shame on one side and exultation on the other but with a soldier’s “mutual salutation and farewell.”

This interaction between the victorious north and the defeated south was the first step in helping to bring a divided and bloodied nation back on the path to becoming the United States again. Did it work? I leave it to you, dear reader, to decide.

On the morning of April 9, 1865, the Army of Northern Virginia was involved in it’s final wartime conflict. The last shots where fired from the front yard of the Peers House. The cannon shot caused some of the last casualties of the war in Virginia.

The countryside around Appomattox Courthouse is beautiful. The photo above is taken near the spot of Lee and Grant’s second meeting. The meeting occurred on the morning of April 10 with both men on horseback. While the surrender in McLean’s front parlor pertained to the Army of Northern Virginia, Grant tried to persuade Lee to convince the remaining Confederate forces to surrender. Lee refused telling Grant that the decision was up to the President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis.

To the right of this photo and out of frame is the location of Chamberlain’s Salute of Honor. I sketched the view looking down the Richmond-Lynchburg State Road (featured sketch).