Dawn at the Canopy Tower started with coffee on the observation deck.

Early morning is the best time to see birds at the Canopy Tower. And the mammals can also be active. Both were actively foraging and close to the tower.

Coffee and TVs, on the observation deck of Canopy Tower.

The Canopy Tower rises above the treetops of Semaphore Hill, meaning that most birds where at eye level or below. No strained necks here, unless you were spotting a raptor directly above. But at this time of the morning there were few raptors on the wing.

As the sky lighten, the forest around the tower came alive. The sift between the nocturnal and the diurnal was underway.

In the front of the tower was a cecropia tree that reached to the heights of the tower. The tree was in flower and it attracted both howler monkeys and Geoffrey’s tamarins.

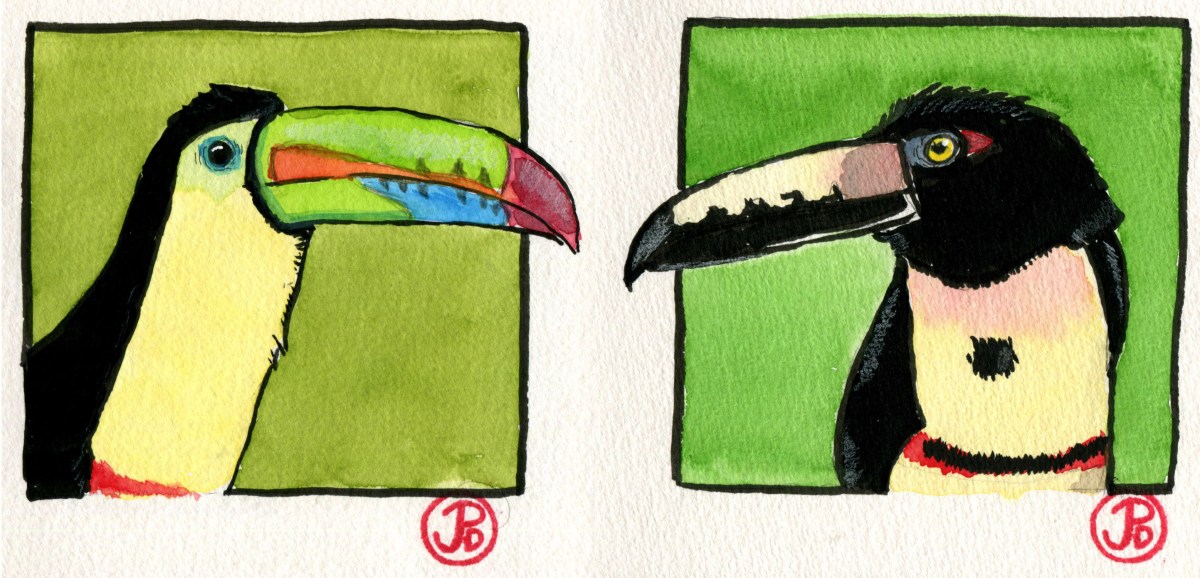

The real stars of the show where the two species of toucan that visited the cecropia in the mornings: the keel-billed toucan and the collared aracari. I had great eye level views of both species, which remains poster birds of the lowland rain forest perhaps none more so than the keel-billed (Ramphastos sulfuratus), the National bird of Belize. This large multicolored billed bird is the quintessential toucan of the tropics. A google images search for the word “toucan” yields many images of the keel-billed toucan over other species.

Poster bird of the Neotropical lowland rain forests.

There are over 40 species of toucans in five genera found only in the Neotropics. The African and Asia continents has many colorful and unique avifauna but the Americans have the family Ramphastidae, the toucans, all to itself.

The keel-billed’s menacing looking cousin, the collared aracari.

Yet another reason to head to the Neotropics to see the birds, so often in Guinness ads and cereal boxes, in the feather!

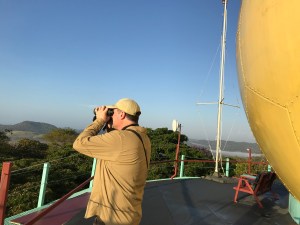

The sketcher in his happy place, dawn on the observation deck of the Canopy Tower, Panama.