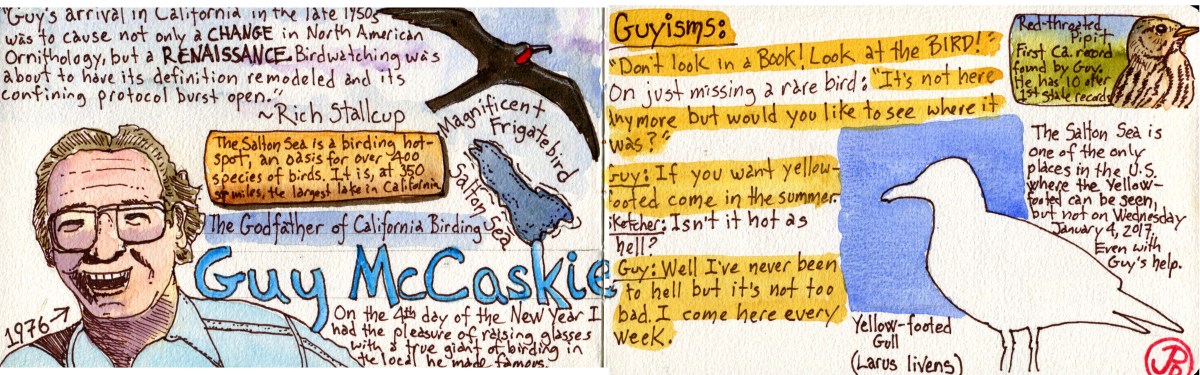

Just west of the Salton Sea, the road begins to rise, just out of Salton City. Slowly you climb up to above sea level and you keep climbing through the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. My target bird for this little desert detour was the elusive Le Conte’s thrasher. This bird have eluded me all over Joshua Tree National Park and I hoping to add this bird to my life list at the known thrasher hotspot at Old Springs Road Open Space Preserve.

I walked the sand in ever widening circles, hoping to catch the bird that looked like a mouse darting from bush to bush, but the the only evidence of the thrasher were it’s footprints in the desert sands.

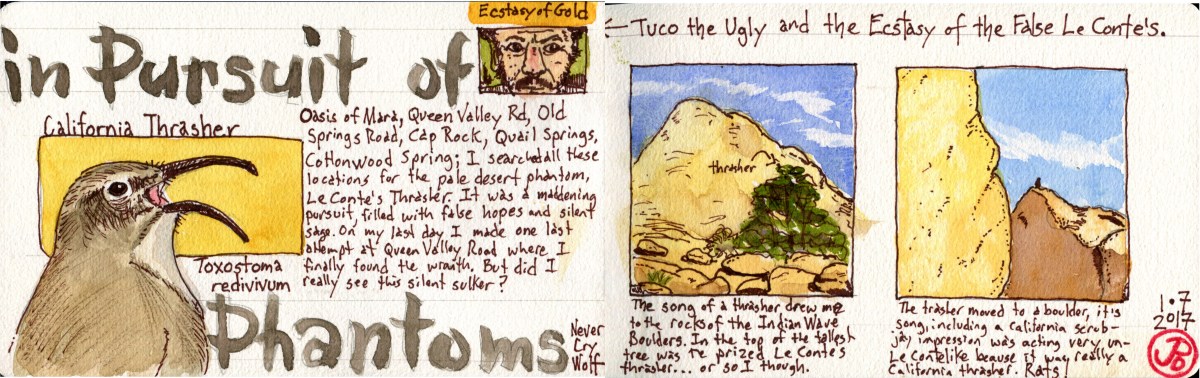

With one last day in Joshua Tree I decided to try one last place for Le Conte’s, a location I had tried before, Queen Valley Road. I walked the road, stopping every once in awhile to listen for the thrasher’s song. I was about 300 yards down the road, when I heard the warble of of a far of thrasher off to the left. I maddening ran through the desert brush, like Tuco the Ugly, in the famous “Ecstasy Of Gold” scene in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. The song seemed to come from the rock outcrop. I scanned the area for any sign of the thrasher.

I finally spotted the thrasher in the upper branches of a tree, signing it’s heart out and mimicking a scrub-jay, which perched in the tree next to the singing thrasher. I was able to get great looks at the very light, sandy thrasher. Le Conte’s thrasher! I watched the thrasher as it moved around, singing from the highest perches around it’s territory.

The singing thrasher on top of a boulder.

I then walked off to the Wall Street Mine. On the way out to the mine, doubt started to set in. There was something about the bird that didn’t fit. Would a Le Conte’s sing in the top of the tallest tree around? Is the Le Conte’s know for it’s mimicry in it’s songs? Everything I had read about the bird was that it was elusive and sang a quiet, hushed song. This was not the thrasher I had just seen. In my desire to see a Le Conte’s, I had convinced myself that this thrasher fit the part.

The abandoned Wall Street Mine, Joshua Tree National Park.

On my return from the mine, I refound the thrasher and this time I confirmed that it was not a Le Conte’s but a California thrasher. And I so I left Joshua Tree without finding the elusive silent-sulker of a thrasher.

Foot steps in the sand are the closest I came to “seeing” the mysterious, Le Conte’s thrasher.

The sketcher at the famous Salton Sea birding trail: Rock Hill Trail at the Sonny Bono National Wildlife Refuge.

The sketcher at the famous Salton Sea birding trail: Rock Hill Trail at the Sonny Bono National Wildlife Refuge.