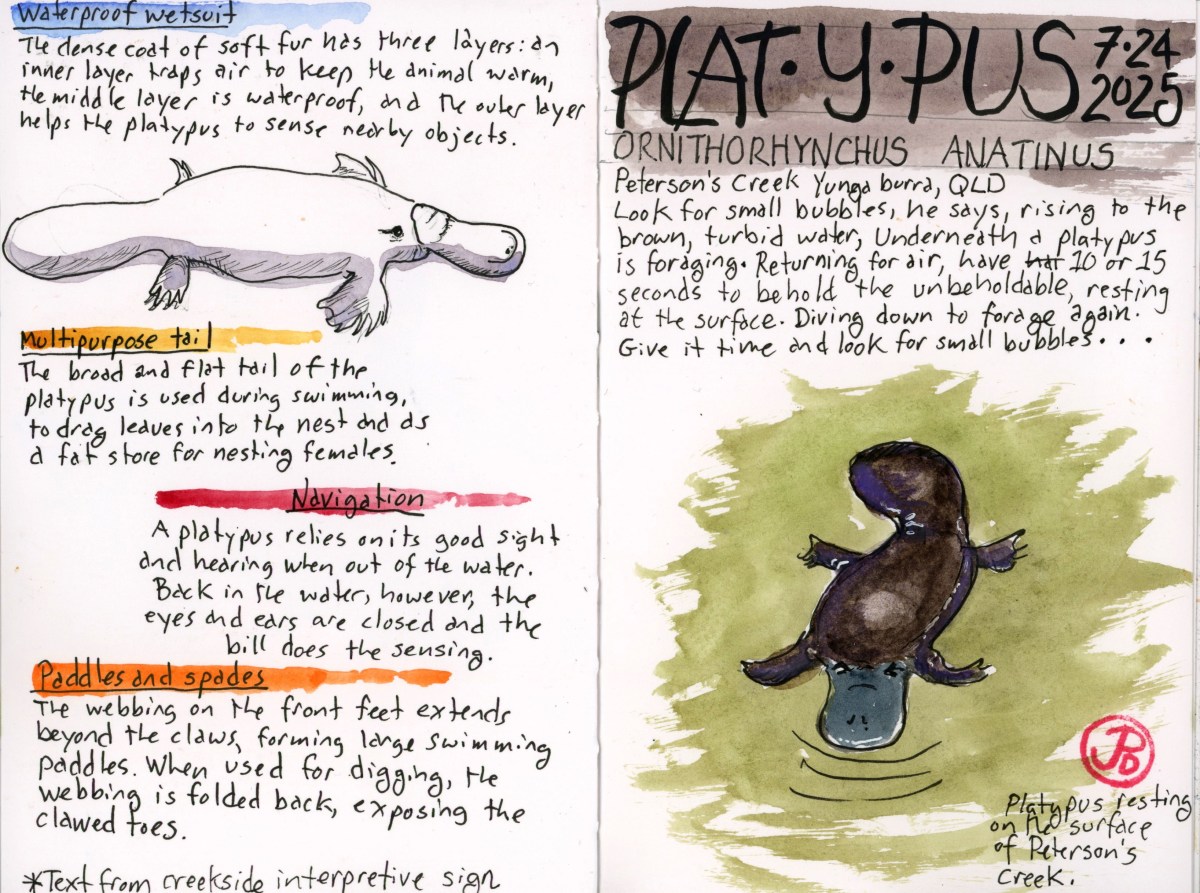

If the cassowary was number one on my bird wishlist, a monotreme topped my mammal wishlist. A unique creature only found in one place in the world: the eastern coastal region of Australia.

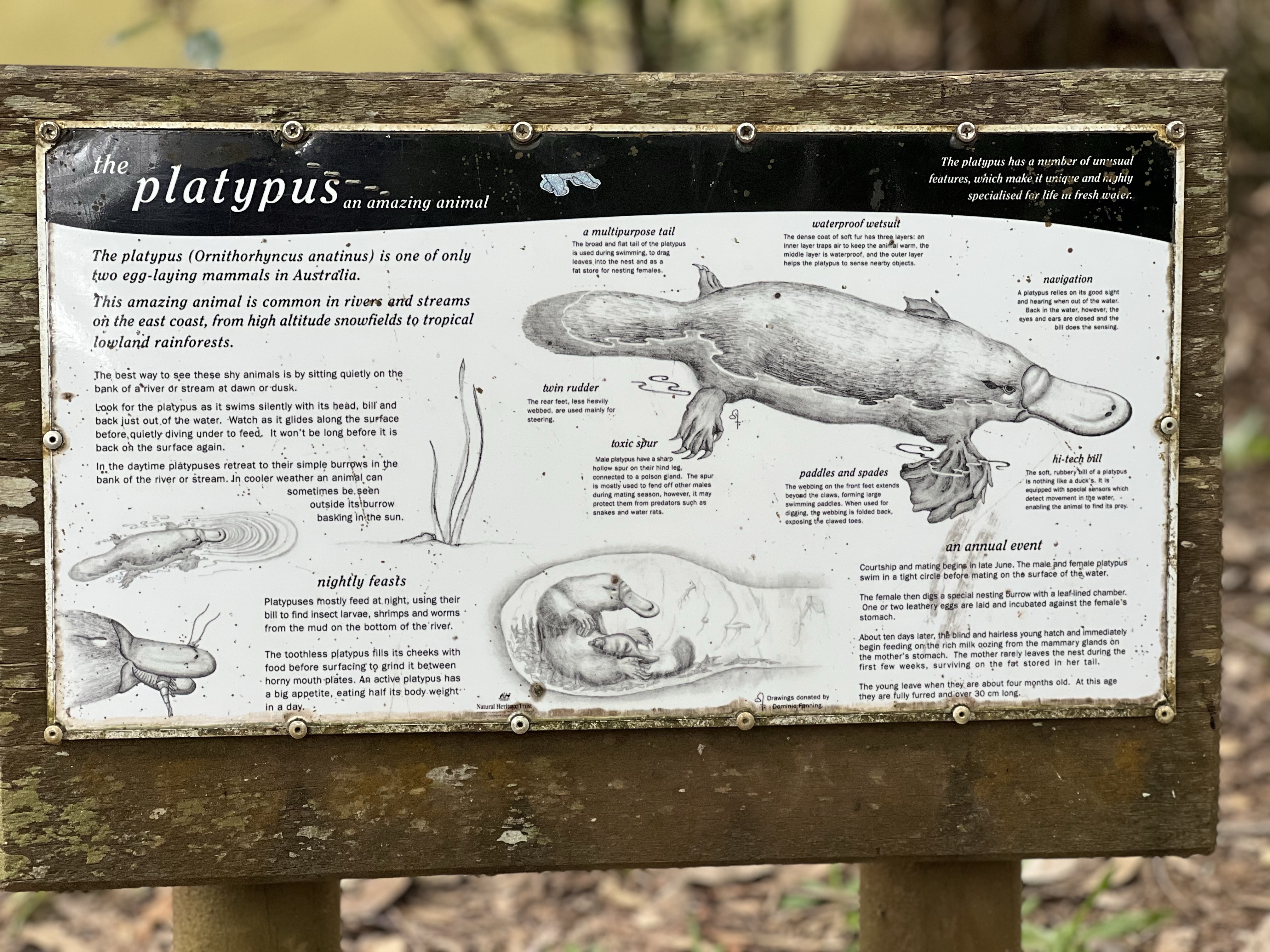

This is Ornithorhynchus anatinus, the platypus.

Before I left for Australia, my guide hinted that we might have a chance for platypus in the way that most nature guides don’t overpromise what they can’t control while giving you real hope of the possibility of seeing a sought after species in the wild.

Our search was conducted at Peterson Creek in Yungaburra, North Queensland.

Out guide told us to look for small bubbles at the surface as we walked along the creek. This was a sign that a platypus was foraging under the brown turbid water. The platypus would come to the surface for a breath of air. It would be at the surface for 10 to 15 seconds and this was the best time to see Australia’s mammalian oddity before it dove down to continue foraging.

Now platypus lore says that the best time to see this aquatic mammal is at dawn and dusk. So why were we at the bank of the creek in early afternoon? According to our guide, we had a good chance of seeing platypus on this stretch of creek at any time of day. Platypus spend a lot of the hours of the day foraging for food. And that is the best time to see them.

It did take long before we saw small bubbles rising to the surface and followed shortly by the platypus itself. The amazing mammal stayed at the surface for about 20 seconds before diving down to forage.

We spent about 20 memorable minutes with the platypus, getting excellent looks and photos.