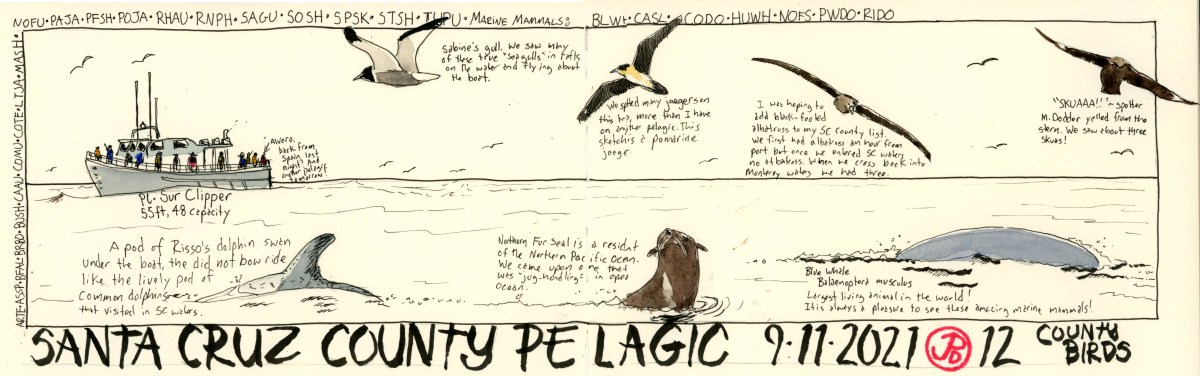

As part of the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators Conference at UC Santa Cruz a group of illustrators set out from Moss Landing Harbor on a Thursday morning for a three hour tour.

Monterey Bay is known for its pelagic birding and the many marine mammals that enter the bay throughout the year. The reason for this lies under the waters. Starting just off Moss Landing’s shores and stretching out to the west for 95 miles, lies the Monterey Canyon. This submarine canyon is larger than the Grand Canyon reaching depths of 11,800 feet and is the largest submarine canyon on the west coast. The deep waters provides a nutrient rich feeding ground for birds, fish, sea turtles, and marine mammals which includes the largest animal on planet earth, the blue whale.

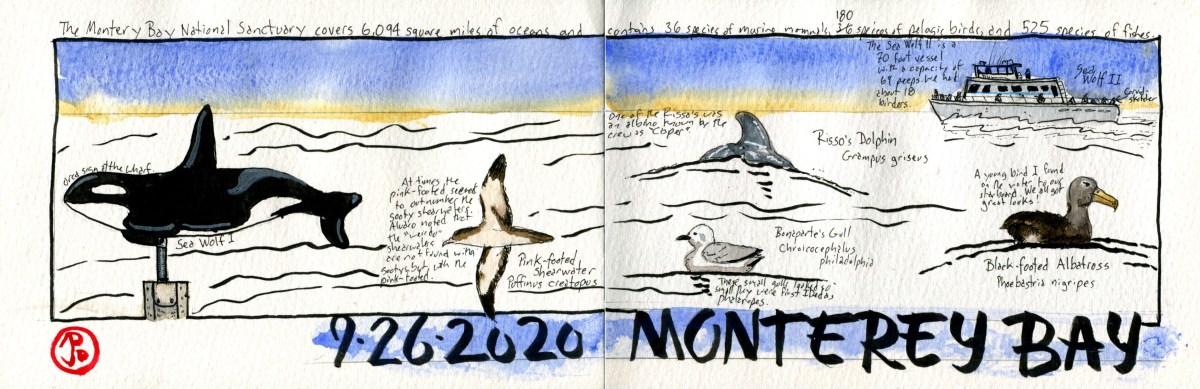

I had first seen blues in the bay on a whale whatch trip out of Monterey when I was a junior in high school (to the disbelief of my biology teacher, but I had the pictures to prove it). It was not uncommon to see gray and humpback whales in Monterey Bay. But on this trip I was going to see a life marine mammal in the wild!

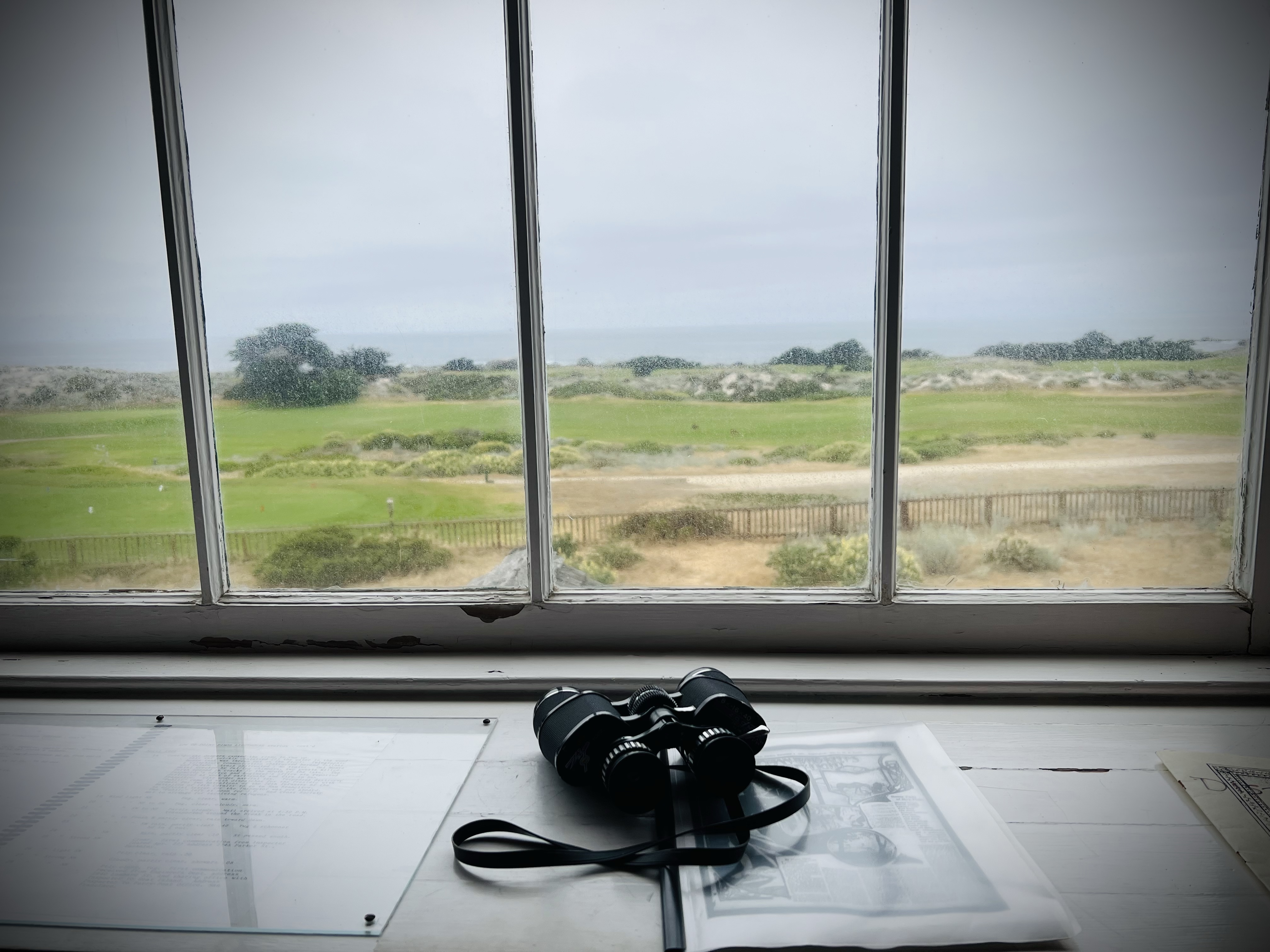

The first marine mammals we encountered in the harbor were sea otter, harbor seal and California sea lion. We turned to the portside at the foraging white pelicans and headed out of the break water to the open ocean and the Monterey Canyon.

It wasn’t long before I spotted our first marine mammal, a lone harbor porpoise (they always seem to be alone), crossing our western bearing, heading to the north of the bay.

After about 15 minutes our captain spotted a blow on the horizon and off we went to find the source. We caught up to the whale, a young humpback and were treated with nice views of its flukes as it dove down. We followed the whale and watched it resurface, take a breath and dive again. We then spotted another humpback and followed it.

Murmurings from the cabin let me know that something was afoot. The captain was on the radio with another whale watch boat and it seemed that they had just sited something special in the southern part of the bay.

As we throttled up heading on a southern bearing, scattering sooty shearwaters in the process, I knew it could be two things: a blue whale or an orca pod. I was hoping it was the latter! Our naturalist was keeping quiet about the sightings to the south.

My first experience with live orcas or killer whales, happened not too far from my childhood home. It was just north on Highwsy 101 on the western rim of San Francico Bay. The setting was the ambitiously titled Marine World Africa USA in Redwood Shores. This amusement park’s main draw, aside from the water skiing show, was the killer whale show where the world’s largest pied dolphin swam in circles and leapt up to snatch a herring from the trainer’s mouth. This is the way most children fell in love with killer whales in the last 1960’s and 70’s.

Since that time, attitudes have changed about keeping these magnificent marine mammals in captivity and training them to do tricks for eager audiences. Marine World left it’s original site on the west side of the bay in 1986 and moved to Vallejo later to be renamed Discovery Kingdom. The amusement park sent it’s last captive orca to San Diego in 2012, ending 40 years of orca captivity at the park.

I now wanted to see orcas in the wild, orcas swimming in a straight line, orcas not doing tricks for an audience. And hopefully we would be seeing a pod soon. We arrived at a location just off the coast of Monterey where there was five other watching boats in pursuit.

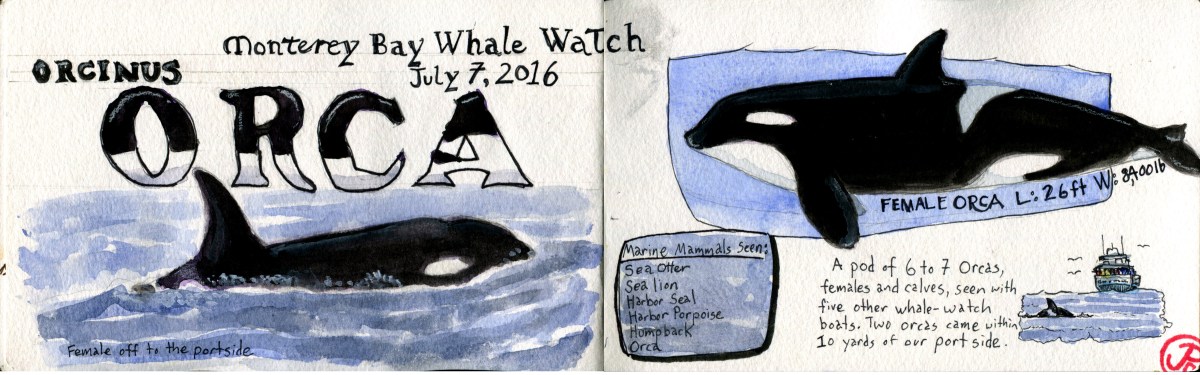

Part of the pod whale watch boats following the pod of orcas. Here a female breaks the surface.

There was a moment of anticipation as we scanned the waters, willing every wave or shadow to materialize into the black back of an orca. Soon we were rewarded with a pod of about seven orcas consisting of females and calves. Two came within ten yards of our boat to give us a look-see!

Recently more and more orcas have been sited in Monterey Bay. It was previously thought that they appeared during grey whale migration to prey on mothers with their calf as they headed north from their birthing lagoons in Baja California to head to their feeding grounds to the north. But now they can be seen throughout the year.

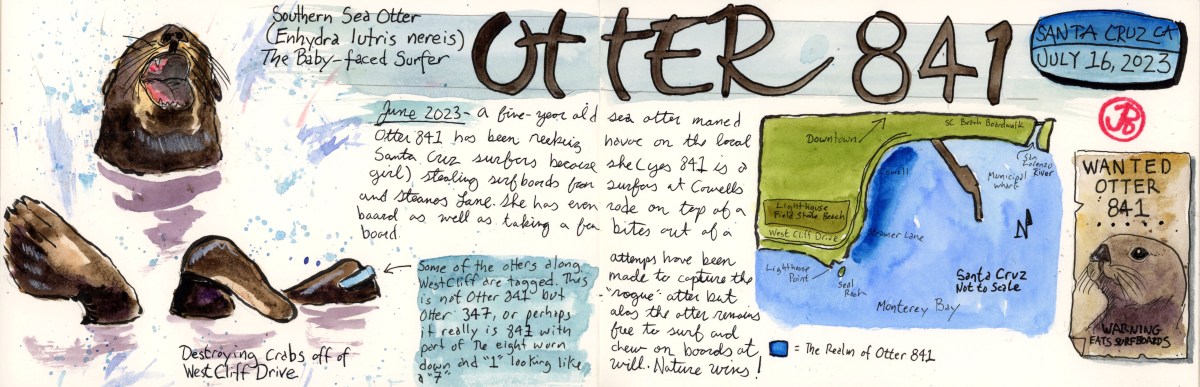

A sketch of a grey whale and calf from the Seymour Marine Discovery Center in Santa Cruz.