Early on a Monday morning I drove to Historic Highway 40, around Donner Summit, to do some sketching.

I love this highway corridor, it’s full of deep California history (native, pioneer, railroad, and highway) as well as personal family history. My parents met at the South Bay Ski Club whose cabin is on Highway 40 near Soda Springs. Without this ski club I would not have come into being.

At the summit I sketched a former gas station. The station was used to fuel highway snow clearing equipment used to keep the highway open in the winter.

The Lamson Cashion Donner Summit Hub is where a lot of the threads of Donner Pass come together (hence the name). Just a short list of the points of interest in this general area are: the petroglyphs, Pacific Crest Trail, the Donner Summit Bridge (the Rainbow Bridge), west entrance of Summit Tunnel 6, central shaft of Tunnel 6, and the Donner Summit Trail.

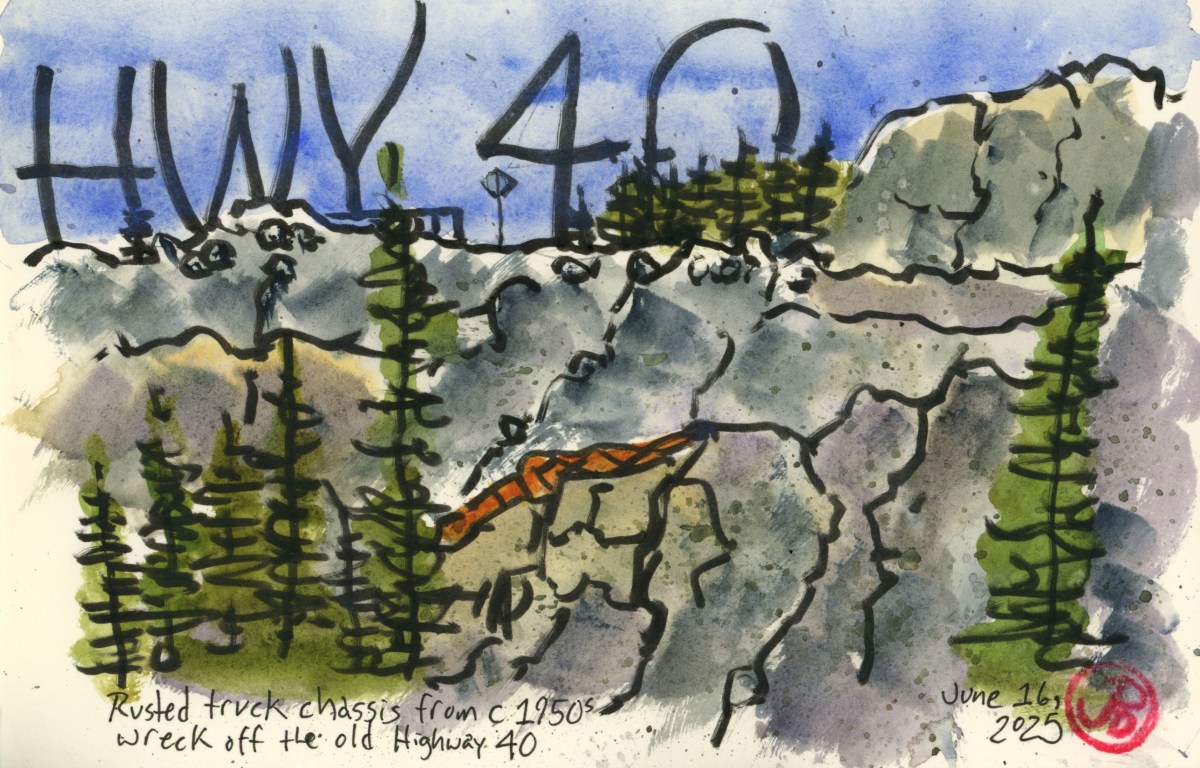

I then headed down the pass and over the famed “Rainbow Bridge”. I was keeping my eyes (at least one eye) to my left, searching for the mass of rusted metal that has been here for about 75 years. There it was.

My father always pointed out this ominous artifact when we would summer here on the shores of Donner Lake. We were historic rubberneckers.

Highway 40, east of Donner Summit is treacherous, as the Donner Party found out when they attempted to scale the pass in 1846. It is also treacherous for auto traffic on the winding, wet, and icy roadbed while heading down grade.

The wreck that my father pointed out is the truck chassis that went over the roadway and settled on a granite shelf sometime in the 1950s. There is not a lot of information about the truck, just that it’s not the “Turkey Truck”. That’s a story for a different post!

I pulled over and found a boulder seat to sketch from using a brush pen to keep it loose and sketchy to the soundtrack of the cooling winds through the pine branches and a male Wilson’s warbler emphatically singing from those branches. I was in Sierra heaven (featured sketch).

After sketching I headed down 40 towards Donner Lake and the Southern Pacific Railroad historic town of Truckee.

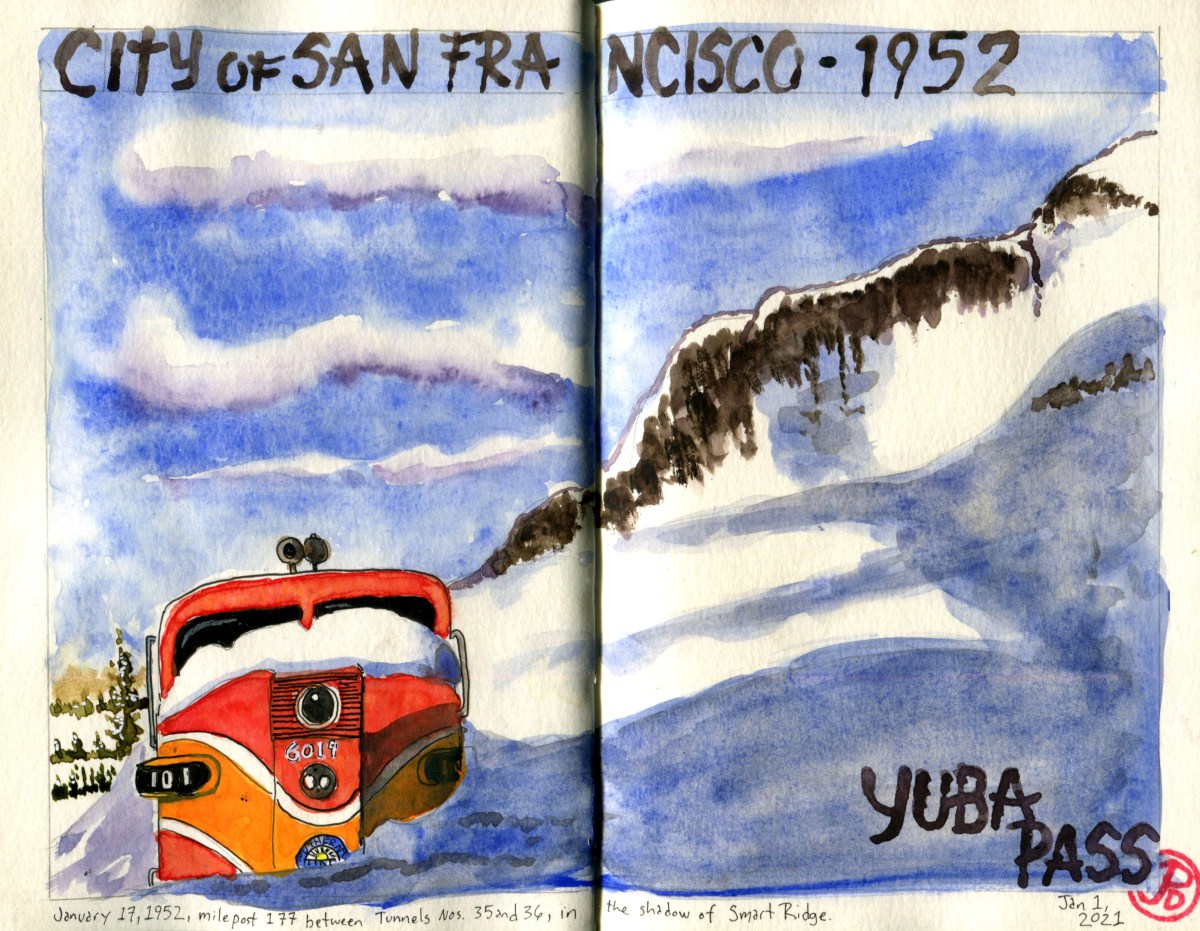

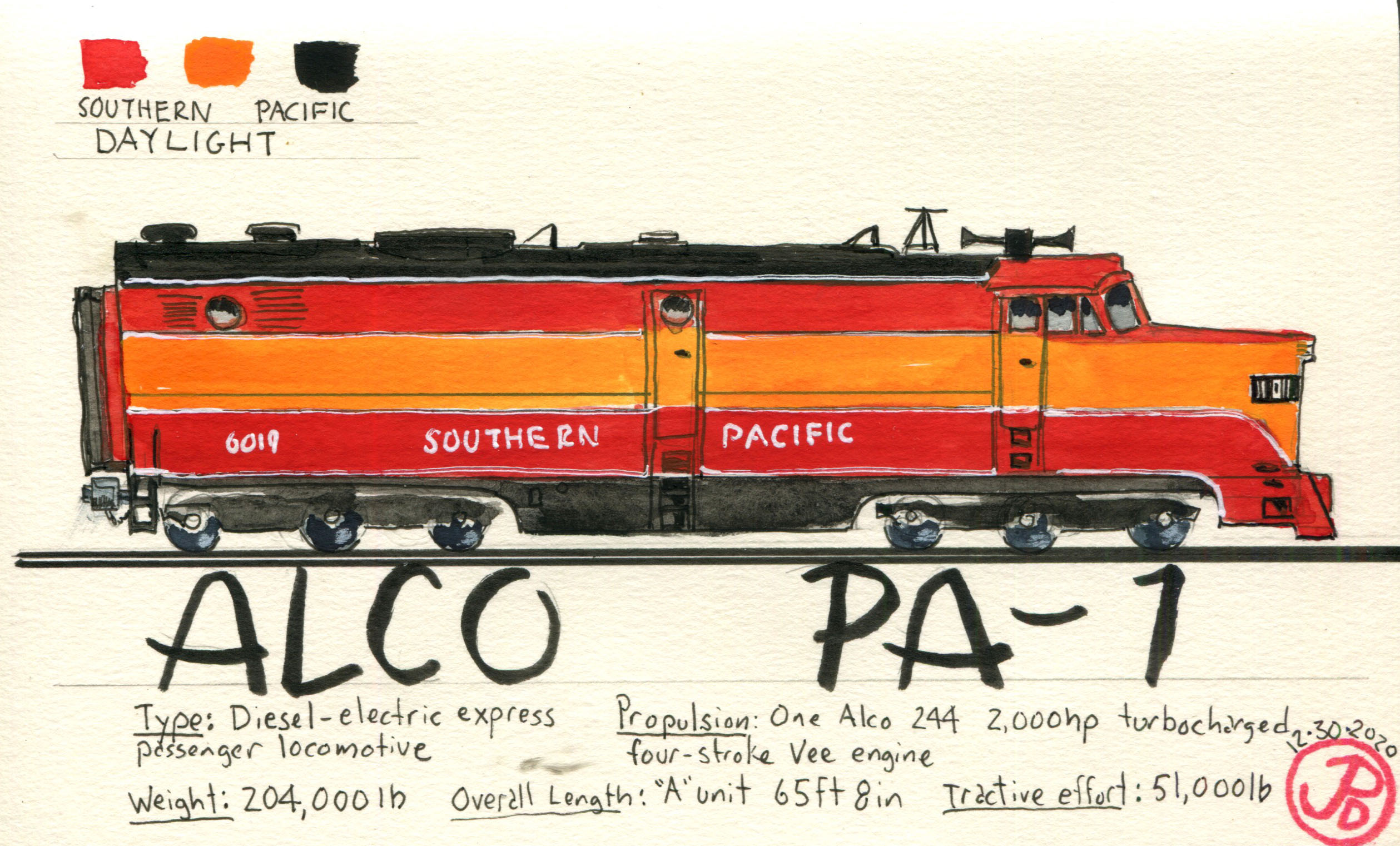

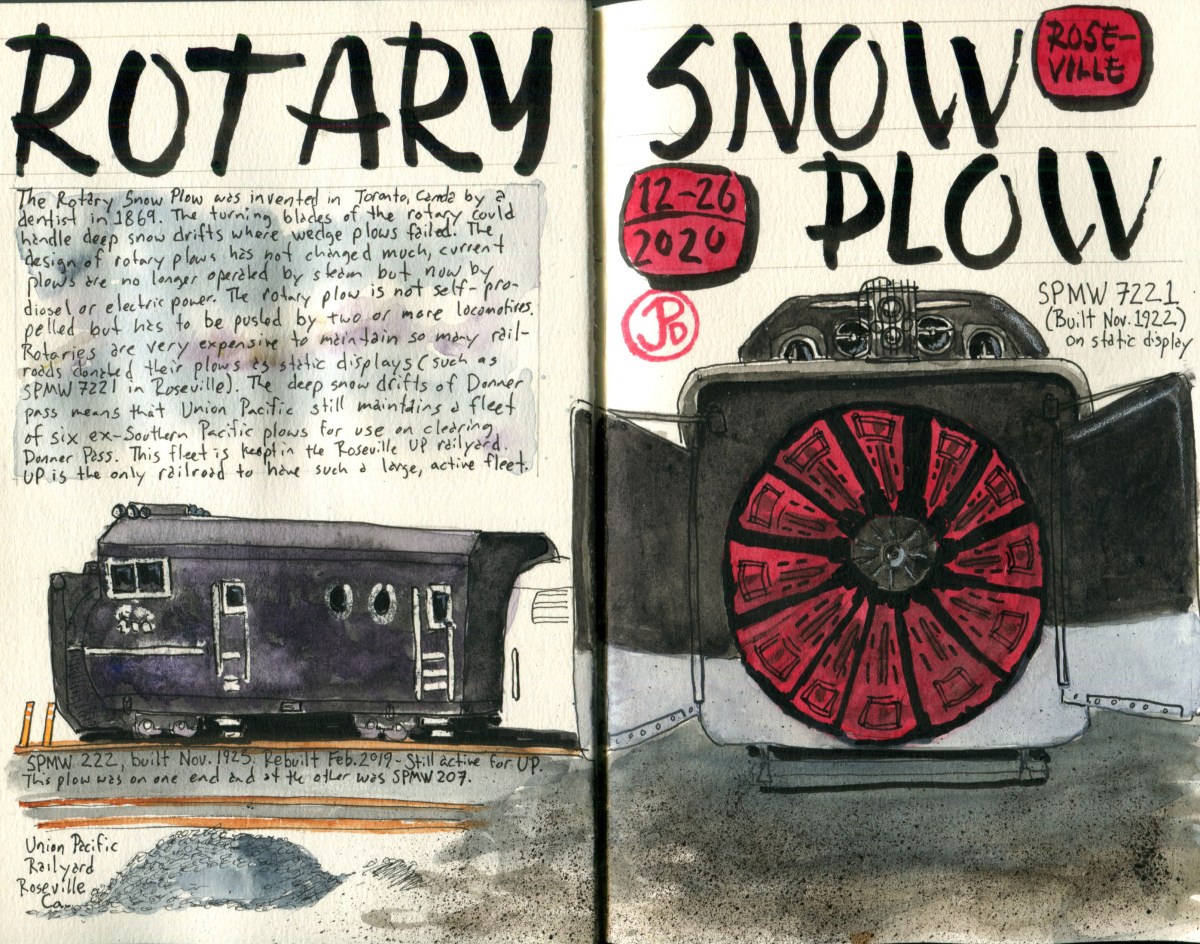

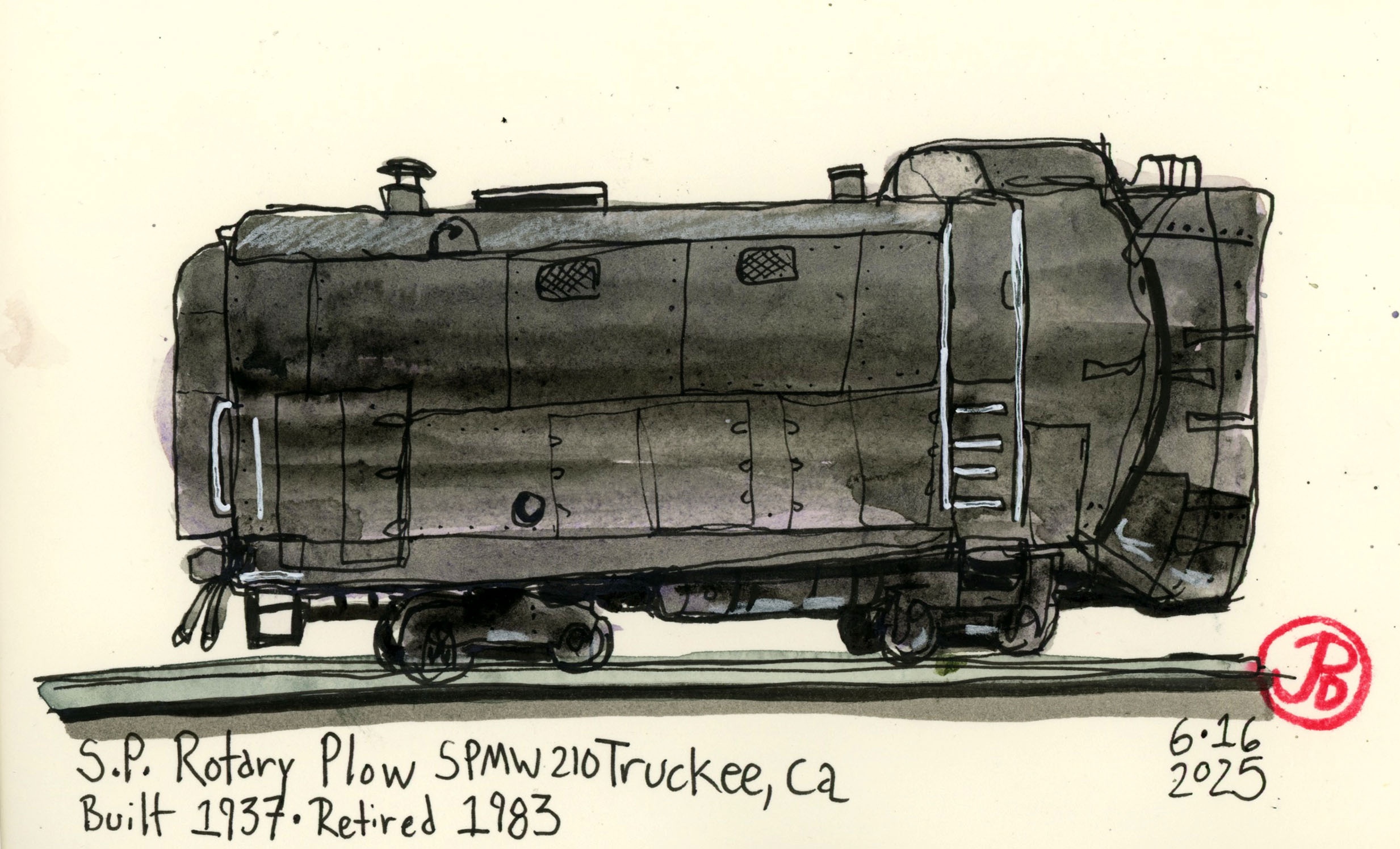

Aside from SP’s iconic cab forward locomotives, no other piece of railroad equipment is as renowned as the rotary snowplow for conquering the grades and gales of Donner Summit.

The rotary plow kept the line open in the deepest winters. And the California State Railroad Museum donated Southern Pacific’s SPMW 210. This historic piece of rail equipment now is on static display alongside the tracks it once kept open in the winter time.

While I have sketched these plows many times before, I decided to try from a different angle with a broken continuous-line sketch.