I was on the hunt for some Bay Area rail history. I was specifically looking for some ghosts of the Southern Pacific Railroad: the Bayshore Yard.

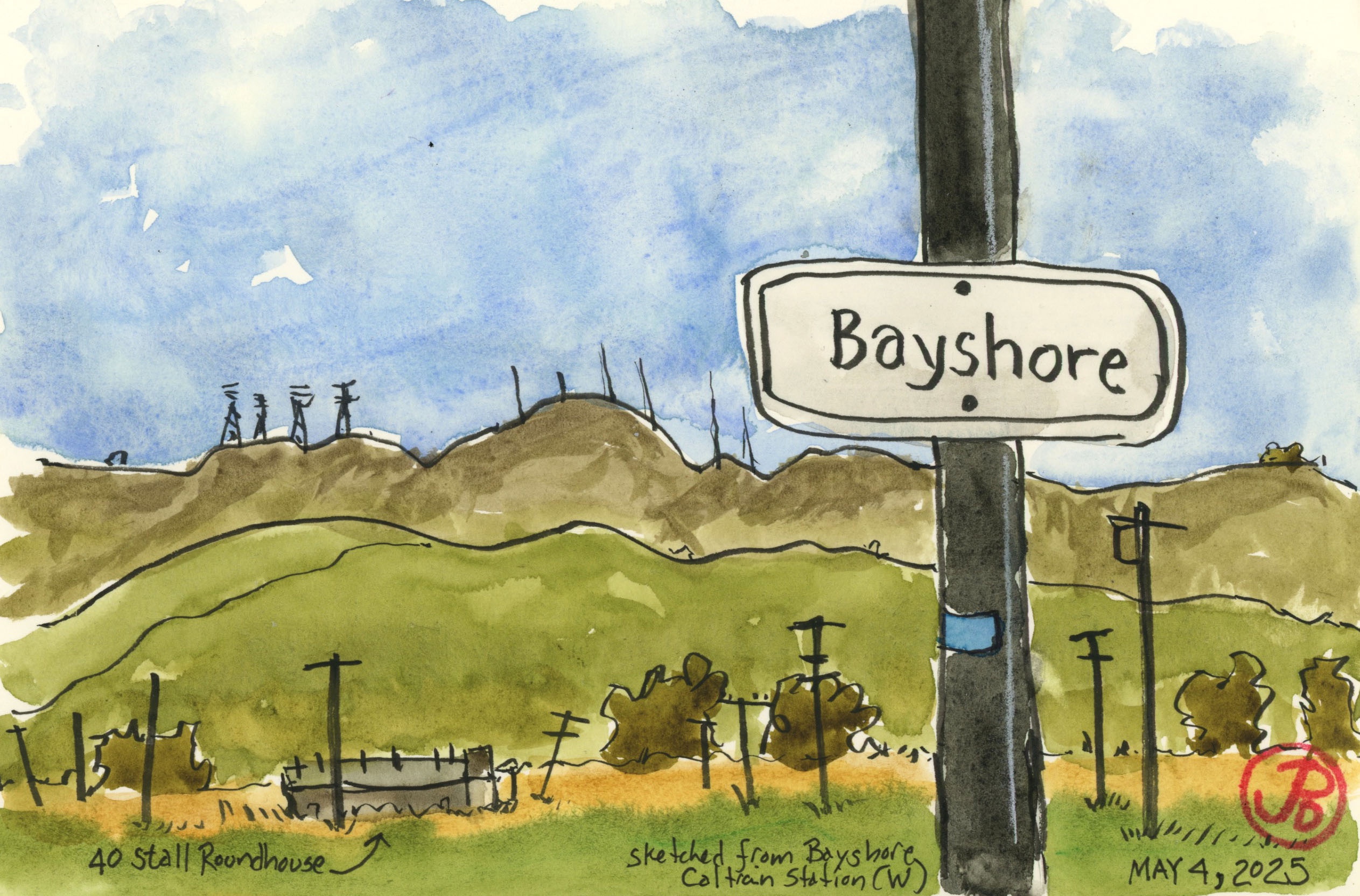

I started my search at the Bayshore Caltrain Station. Uncanny! Who would have thought?

To the west of the tracks is a large overgrown open space punctuated by wooden power poles and bordered by the San Bruno Mountains. On the far edge of the open fields are some dilapidated and graffitied buildings.

The brick roundhouse and the tank and boiler shop are the only remaining structures of a once bustling train yard and shops. How bustling?

The yard contain 50-65 miles of track, had a capacity of over 2,000 freight cars, and employed 3,000 people.

This was SP’s most heavily travelled stretch with 46.5 million gross tons per mile during WWII.

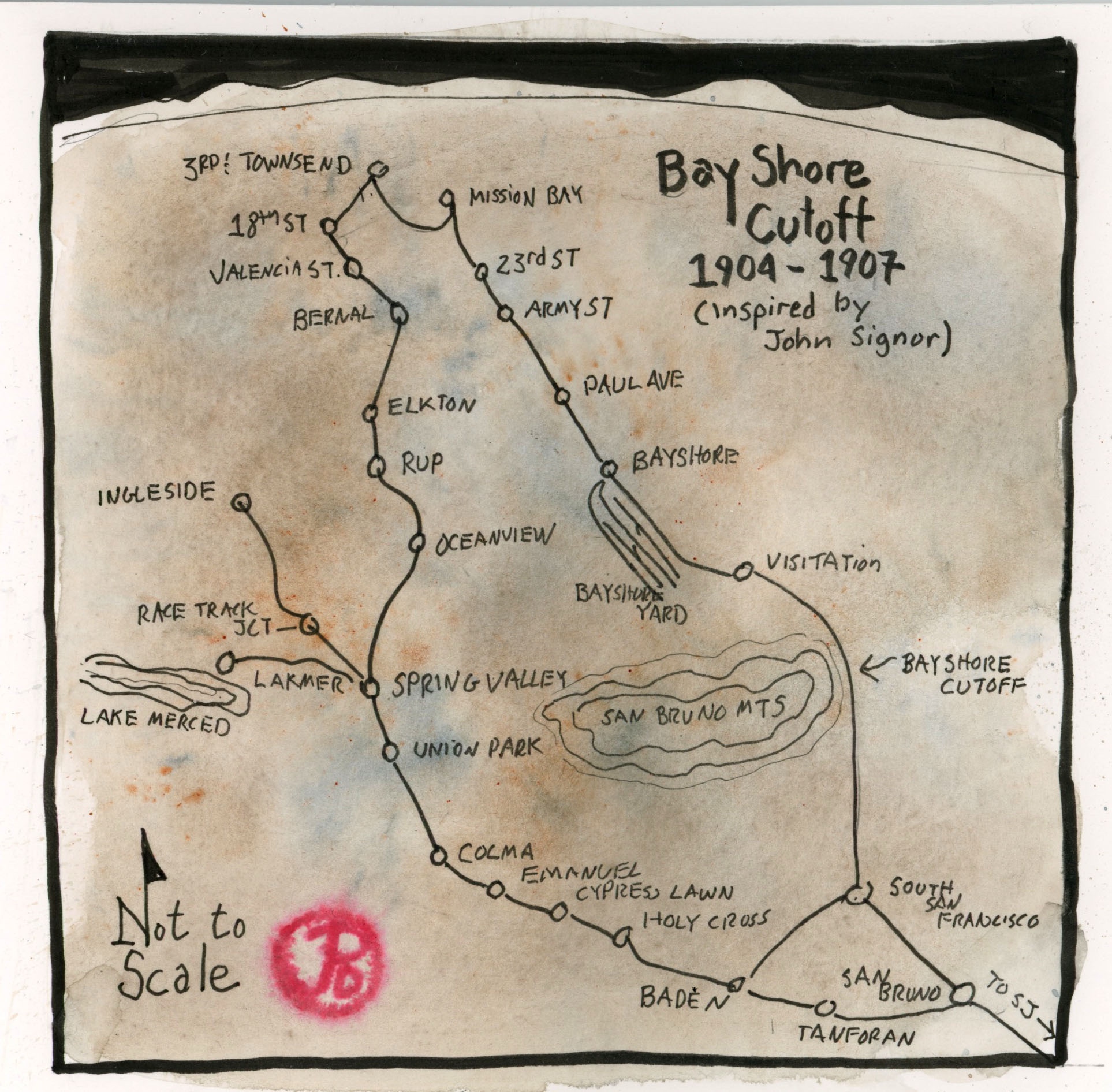

The story of the yard and shops starts with the Bayshore Cutoff.

As the name implies the Bayshore Cutoff is a short cut that straighten the line around San Bruno Mountain’s southern edge, from San Francisco to San Bruno.

The cutoff was completed 1907 and cost Southern Pacific $7 million. One reason for the high price tag is that the railroad had to construct five tunnels (20% of the cutoff was in tunnels). The fill from these tunnels was used to fill in Brisbane Lagoon which became Bayshore Yard and Shops.

The benefits of the cutoff were: saving more than three miles on the route, reducing the curvature of the line, and flattening the grade. The improvements cut travel time from San Francisco to San Jose by 30 minutes. The cutoff is still in use today, conveying passengers to and from San Francisco on Caltrain.

For my Bayshore sketch I took a position on the southbound platform and sketched the Bayshore Station sign in the foreground and the feral field and roundhouse in the background. In the far ground is San Bruno Mountain.

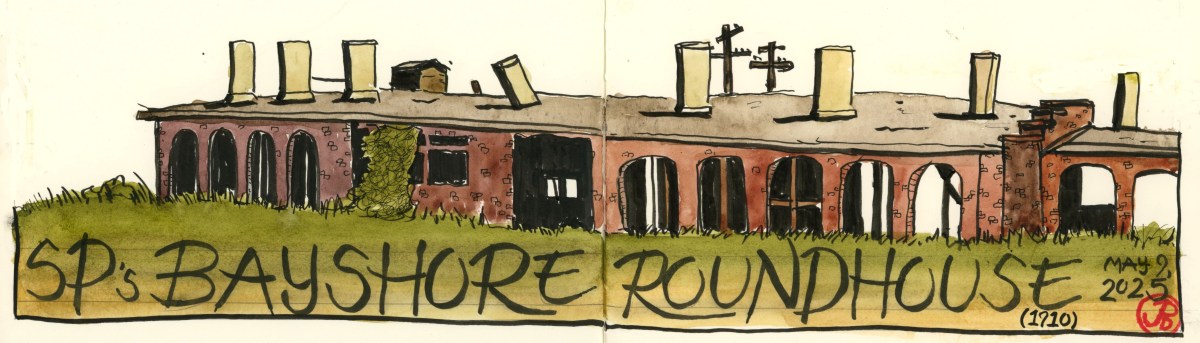

After work I headed up to Brisbane with the intent of sketching the roundhouse from Bayshore Boulevard. The roundhouse is close to the street but the former yard is enclosed in fencing. I was able to find a gap in the eucalyptus trees to get a panoramic sketch (sans graffiti) of Southern Pacific’s Bayshore roundhouse.