One of the legendary railroad routes is the section of the Transcontinental Railroad that climbs the western flank of the Sierra Nevada Mountains up to Donner Pass. The construction of the railroad was an engineering marvel and much of the original route is still in use.

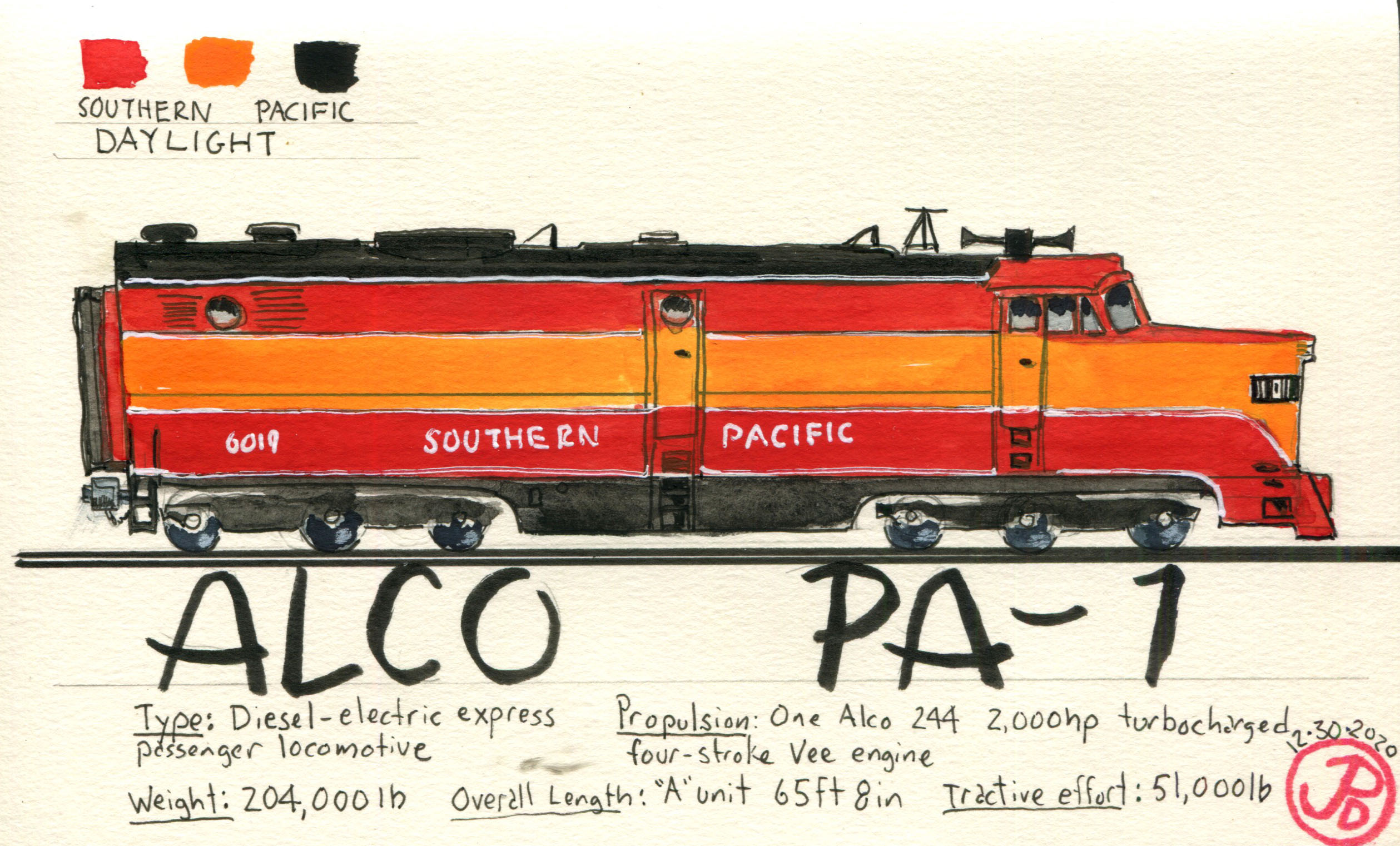

Southern Pacific used their AC articulated cab-forwards to tackle the grades and heavy freight over the pass and now the world’s largest articulated locomotive would be climbing up to Donner Pass for the very first time. And I planned to be there.

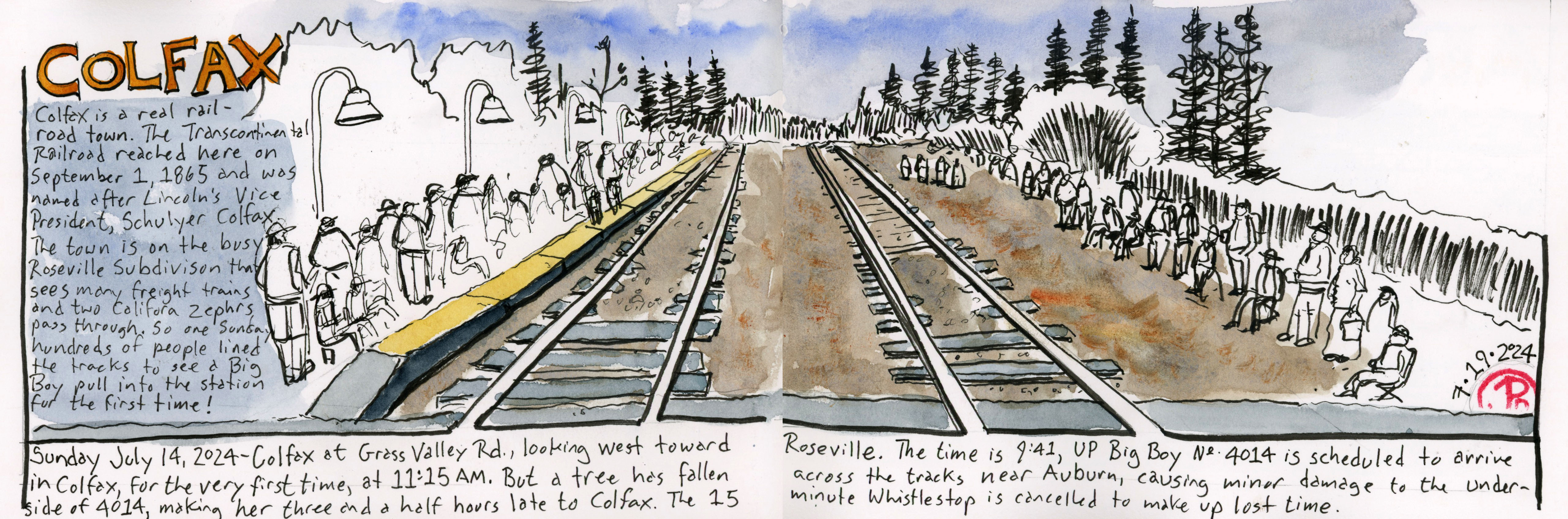

There was a planned 30 minute whistle stop at the historic railroad town of Colfax at 11:15.

I was in Colfax an hour and a half before arrival and more and more people were streaming into town.

4014 left Roseville on time but was halted when the train hit a tree that had fallen near Auburn. The UP tracking app noted that 4014 was “currently stopped near Auburn”. At first I thought it was just a maintenance stop but then word spread that Big Boy had hit a tree and there was some damage to the underside. This was not good. Especially for the hundreds of people waiting in the heat for 4014 at Colfax.

Word spread that the locomotive might have to be towed back to Roseville. The train was now an hour late. I decided to head back to Penn Valley, to air conditioning and the second half of the European Cup Final. I would continue to monitor the UP tracking site. But I had to beat the heat in Colfax.

Just after the game ended (Spain was European champions for the fourth time), the tracker read, “4014 currently moving near Auburn”.

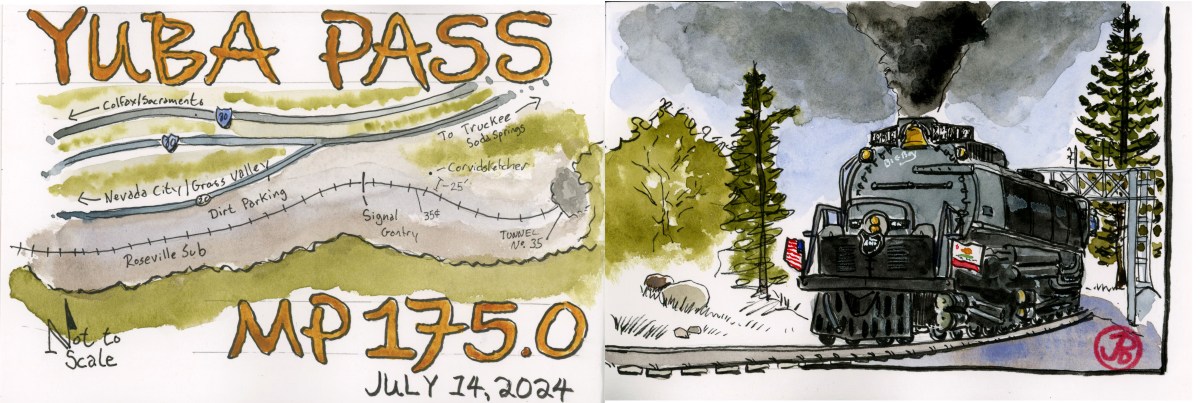

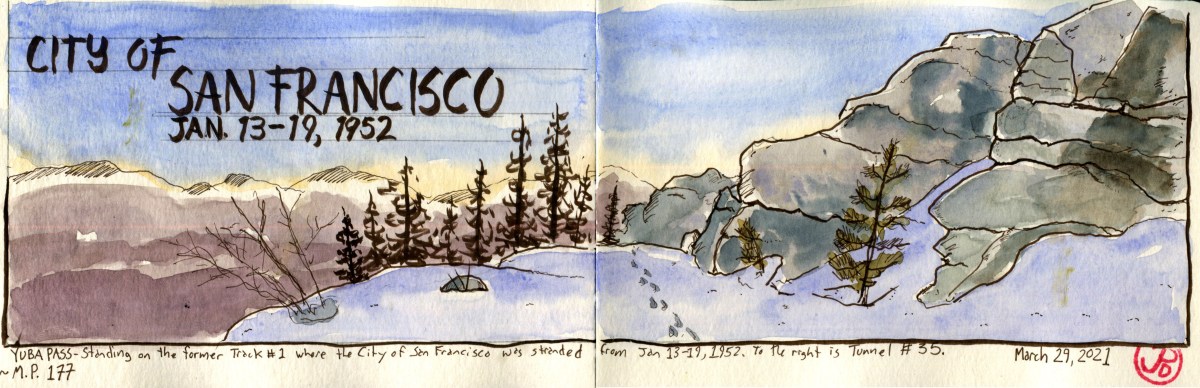

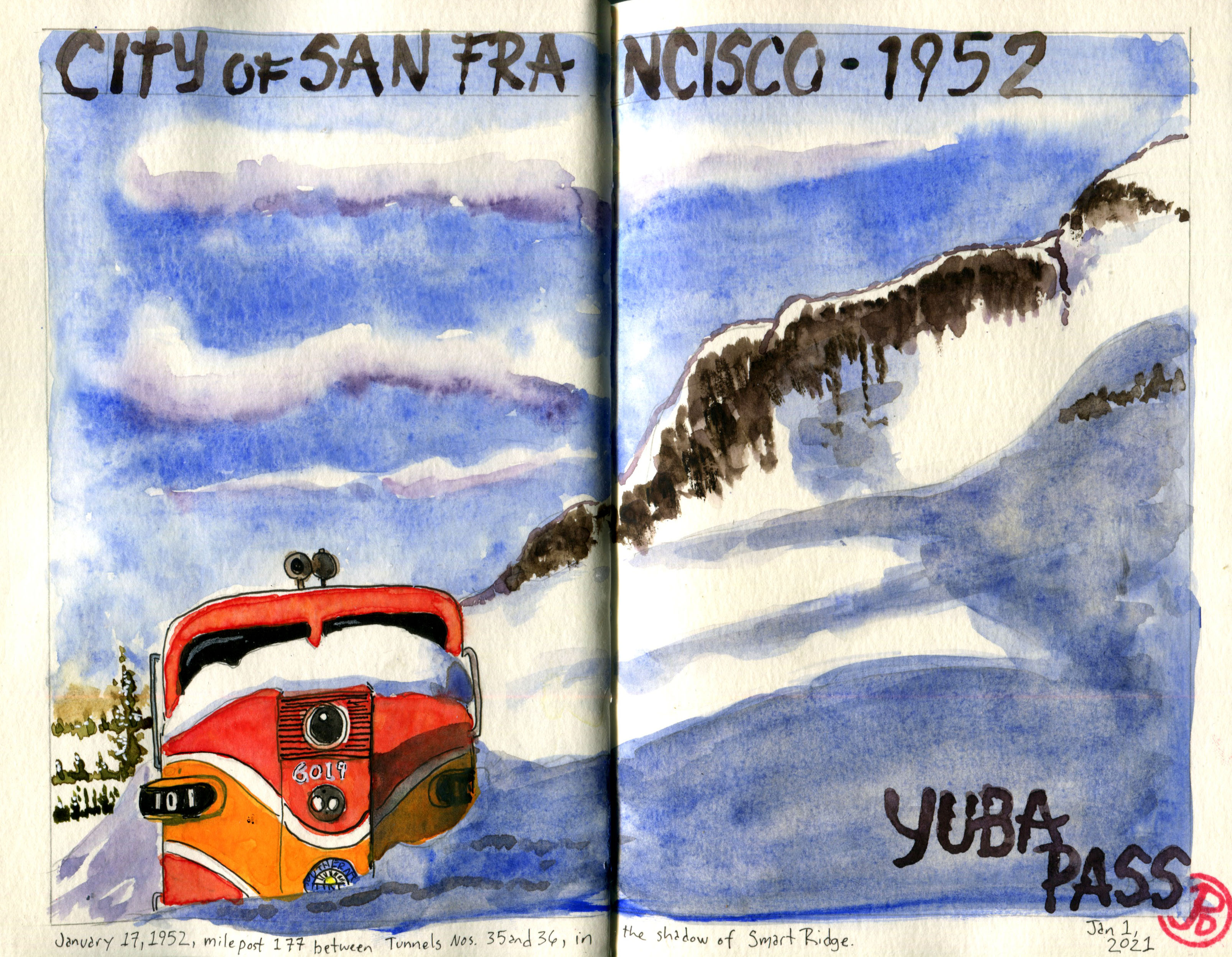

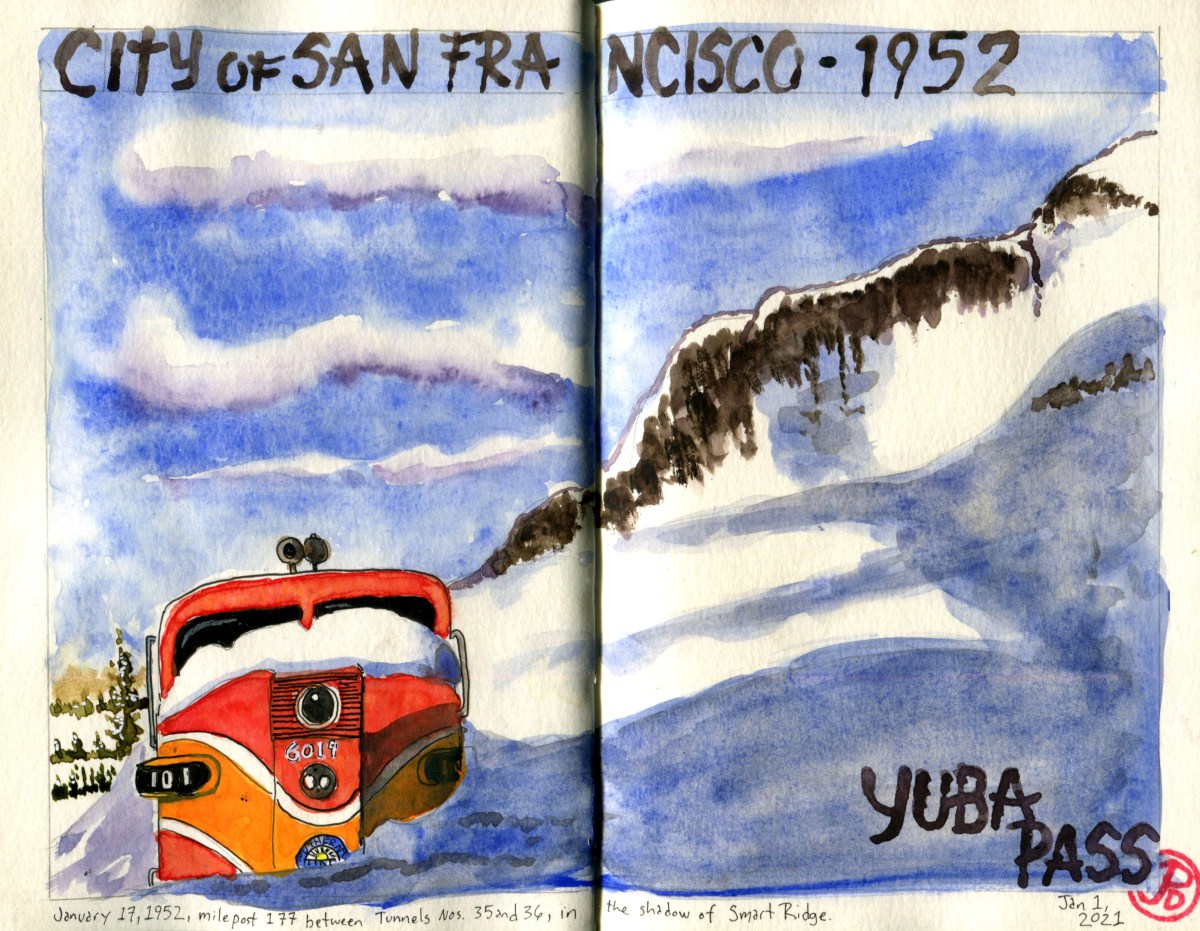

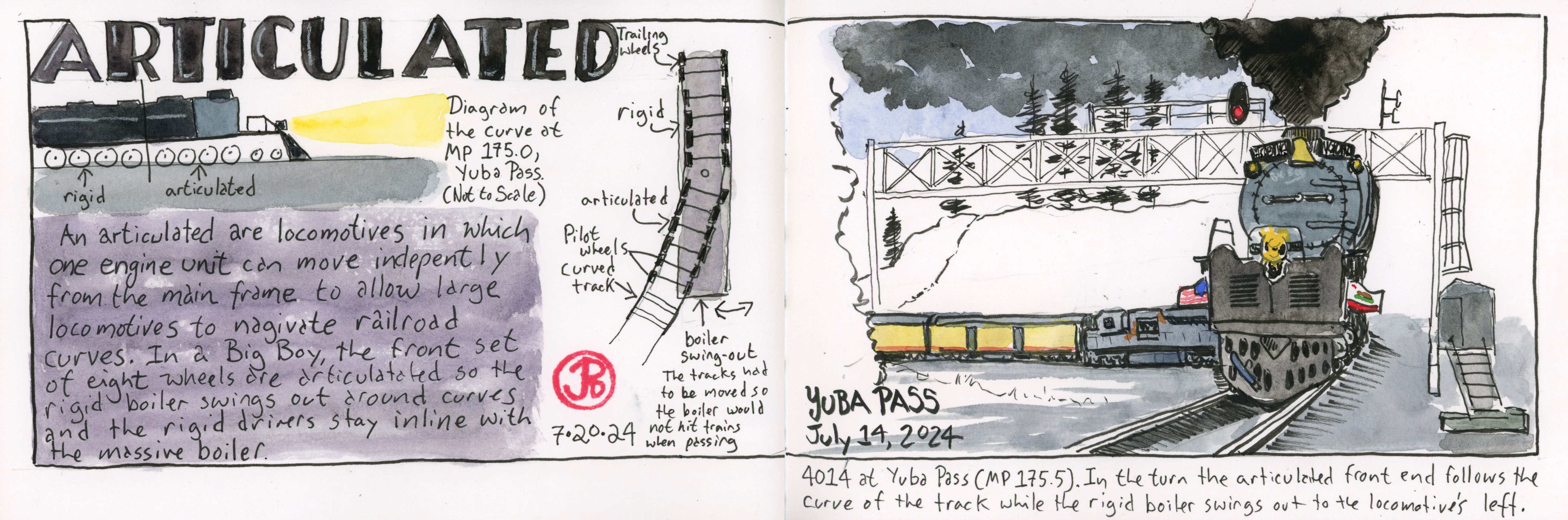

My plan was to drive on Highway 20 to where it merged with Highway 80. This was Yuba Pass and I wanted to see Big Boy in this historic location.

I arrived and there were plenty of other rail fans lining the tracks at Yuba Pass. This was a good sign because 4014 was still climbing the grade and had not reached my position.

After about a 45 minute wait a plume of steam exhaust appeared down line and the mighty roar of the Big Boy filled the cut.

Then the iconic articulated giant appeared working up grade towards my position near the signal gantry. 4014 was putting on a show that enveloped all the senses.

As 4014 rounded the curve, the articulated properties of the design were in full display. While the leading truck and front drivers rounded the curvature of the track the boiler remained rigid making it appear that the drivers and boiler were separating. Afterwards I did a spread to understand the articulation design (below).

After the train disappeared into the tunnel, I headed back to my car and was soon driving east on Highway 80. To my right, I could see the tell-tale exhaust up the hill on the railroad grade. Soon I was pacing with 4014 and I then pulled ahead and planned to head to Soda Springs to see the steam mammoth as she neared Donner Summit.

I made it to Soda Springs off Historic Highway 40 and the biggest challenge was finding a place to park as there were many people waiting trackside for the arrival of the Big Boy.

I found a parking spot and headed down to the grade crossing. There was a festive atmosphere around the tacks and to the south many Cal Fire trucks and personal (including Smokey) looked and listened down track for the first appearance of the 4-8-8-4.