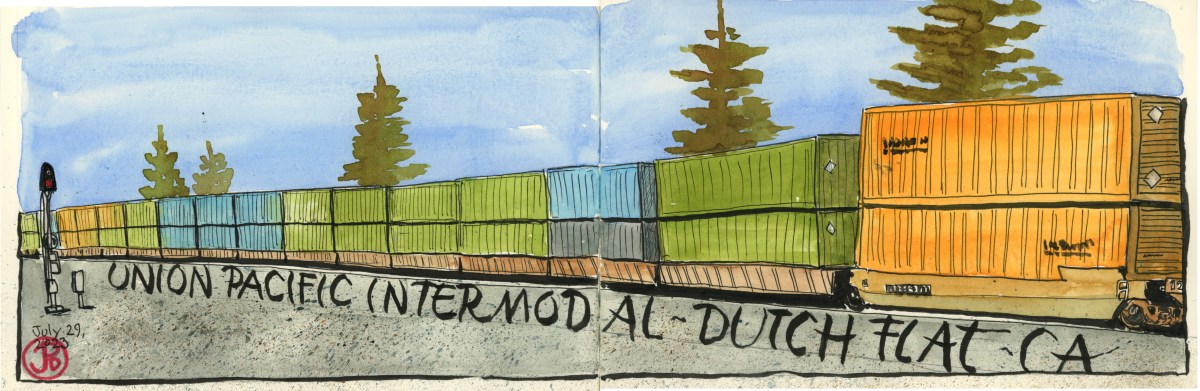

I once chased the California Zephyr Train # 6 from Roseville to Truckee but now I wanted to chase what really makes Union Pacific the big bucks: an intermodal freight train!

Intermodal is freight that is transported by various forms of transportation: ships, trains, planes, and trucks, for example. Most of the intermodal freight trains across the Sierra Nevada consist of double stacked freight containers, known as Container on Flatcar (COFC), or single truck trailers on flat cars, known as Trailer on Flatcar (TOFC) or piggybacks.

I first caught sight of my freight as it really began it’s climb up the western slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains at Cape Horn, just out of Colfax. (I had just missed it’s passage through Colfax.)

I attempted to follow the train on Historic Highway 40 with some stretches on the highway that relegated Highway 40 to a little used country road: Interstate Highway 80.

Catching up with the train should not be a problem (even on windy side roads) because the average speed of a freight train climbing up to Donner Summit is between 25 to 30 miles per hour. And sometimes the freight’s speed could be even less.

I headed east on a patchwork path of Historic 40, side roads, and Interstate 80. When I thought I was sufficiently ahead of the intermodal, I searched for the mainline. This consisted of picking either side of the road, north or south (at Blue Canon I picked the wrong side), and then driving until I came upon railroad tracks. This I did at the grade crossing at Dutch Flat. The eastbound signal light was green indicating that the train had not passed this point yet.

I picked my vantage point and after about ten minutes I could hear the rumble of the diesel-electric locomotives as they climbed the grade followed by the sounding of the horn, and then the crossing gates were triggered and the safety arms lowered to stop traffic.

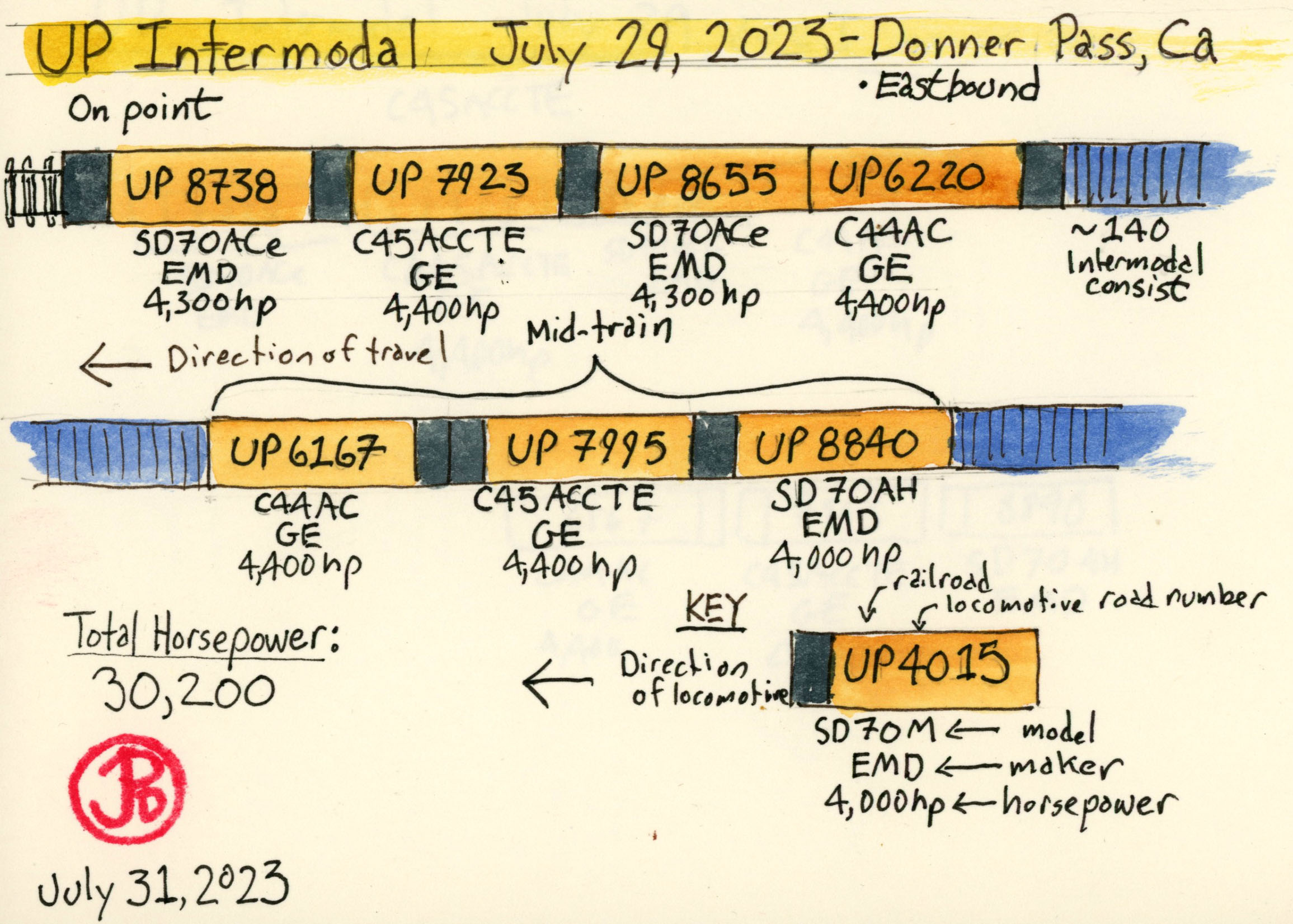

Union Pacific No. 8738 came into view. No. 8738 is an Elctro-Motive Diesel (EMD) SD70ACe. These 408,000 pound locomotives generate 4,300 pounds of horsepower and this consist featured four locomotives on point and three more mid-train. These seven locomotives generate a combined 30,200 pounds of horsepower. They need this power to pull/push the heavy loads up and over Donner Summit.

Just to provide some context, the Southern Pacific locomotive that was designed to tackle the grades and snowsheds of Donner Pass were the cab forwards. The last cab forward built, the AC-12 class No. 4294 (which is preserved ay the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento) weighed 1,051,000 lbs (locomotive and tender) and the locomotive produced 6,000 pounds of horsepower.

When compared to standard vehicles on Interstate 80, 30,200 horsepower equals about 30 semi trucks or 150 Toyota Camrys.

Once the train passed I drove down the road into “downtown” Dutch Flat and headed back toward the highway. I came to a grade crossing where the last few cars where just passing. The arm rose and the race was on!

I hit the highway trying to outpace the freight train as well a finding a new point to see the train. I made it to my tried and true spot at Yuba Pass, where Highway 20 merges into 80. I knew I had not missed the train because the signal on the gantry above the rails was green. I must have made really good time because I had to wait almost 30 minutes before I heard the rumble of the diesels laboring on the hill. The intermodal passed and this time I got a wave from the conductor, seated on the left side of the cab. In the days of steam, this would have been the fireman’s position and the conductor would have been riding at the end of the train in a caboose.

The average length of a freight train on a Class I railroad is about 5,400 feet. At Soda Springs I wanted to do a little experiment with the intermodal to see if I could come to an estimation on how many cars where in the consist. This started with timing the train from the grade crossing at Soda Springs. How long would the train take to pass a single point? The answer was four minutes and 54 seconds. That was almost a five minute wait for any motorist at the crossing!

Now for a little railroad mathematics. I estimated that it took about 2 seconds for one car to pass so I divided 294 seconds (5 minutes and 54 seconds) by 2 and got 147 train cars. I then subtracted the number of locomotives (7) and came to an estimation that this freight train consist consisted of 140 cars. An intermodal of this length takes a lot of trailer trucks off the roads. Just how many trucks?

I estimated that about 75% of the train consisted of double stacked Container on Flatcar (COFC) which is 105 cars and the remaining 35 cars were Trailer on Flatcar (TOFC). 2 times 105 is 210, add 210 to 35 and we get 245. So this intermodal freight train removes about 245 trailer trucks from Highway 80. Every motorist motoring to Lake Tahoe or Donner Lake should be thankful these Union Pacific freights that put in the hard work that make life a little easier.

Based on my field photos I was able to get the road numbers of all seven locomotives on the freight train. Using a Union Pacific roster I was able to identify the maker and model of each locomotive and it’s horsepower output. There where three EMD (Electro-Motive Diesel Inc.) and four GE (General Electric) locomotives. I put this information into a locomotive map showing the road number, model, maker, horsepower, and direction of travel for each locomotive. The total horsepower output for all seven locomotives was 30,200 hp.