There has been a museum on my sketch list for a long time and I used my fall break to finally visit it.

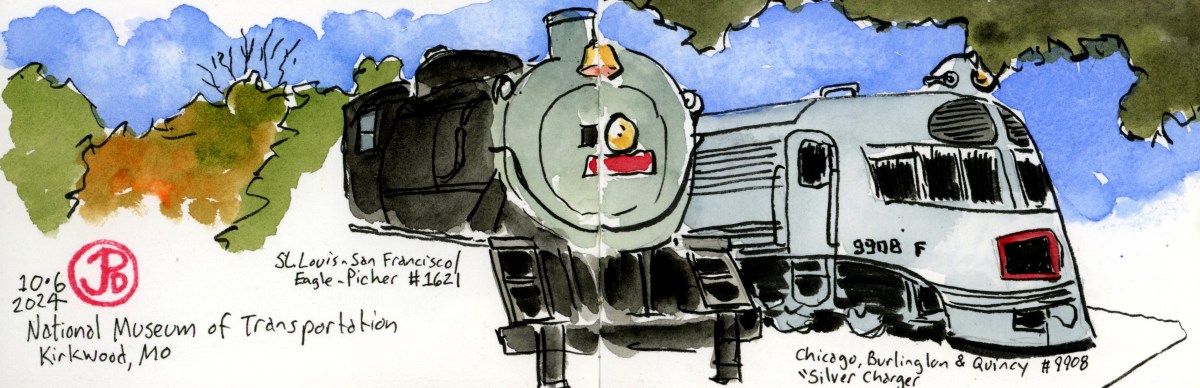

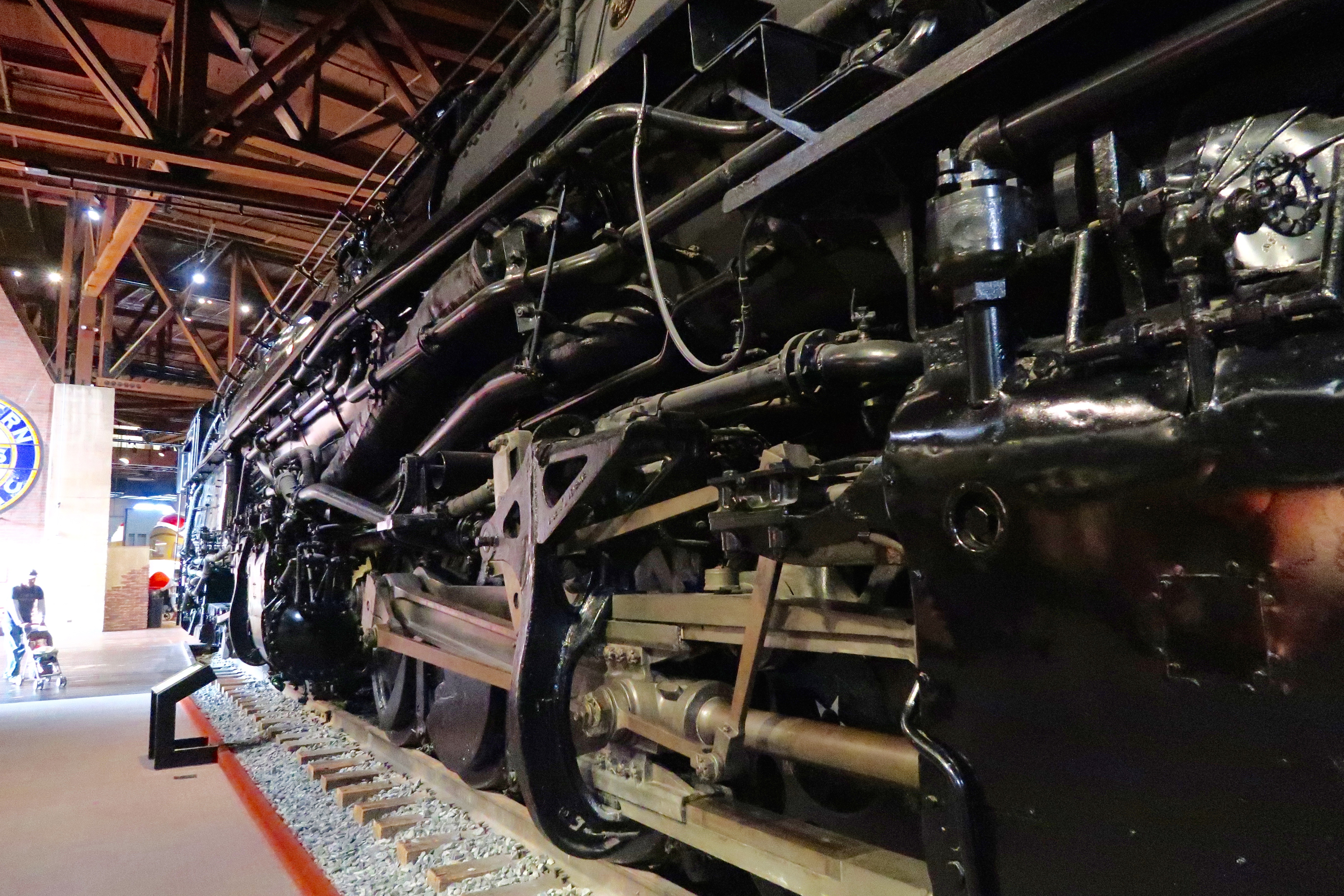

The National Museum of Transportation is in the St. Louis suburb of Kirkwood, Missouri. The 42 acre museum was founded in 1944 and has a large collection of railroad history (and cars and planes).

The museum has it’s own railroad spur to the Union Pacific mainline (formerly Missouri Pacific Railroad) so the larger locomotives in its collection can be shipped on rail.

I made up a sketch list before my visit and there were a lot of iconic locomotives to render in ink and watercolor.

I was going to be busy, very busy!

Visiting this museum is like having my favorite train book as a child, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of North American Locomotives by Brian Hollingsworth, come to life. As a child I thought: “I’d like to see that locomotive!” And now I was about to! In fact the museum has 13 iconic locomotives featured in this book. The reason I knew this museum even existed was the common refrain in the book, “now displayed at the Museum of Transportation at St. Louis, Missouri”.

I planned to spend a good deal of time on my Sunday visit at the museum sketching. I would do all the line work in the field and then add watercolor back at my hotel.

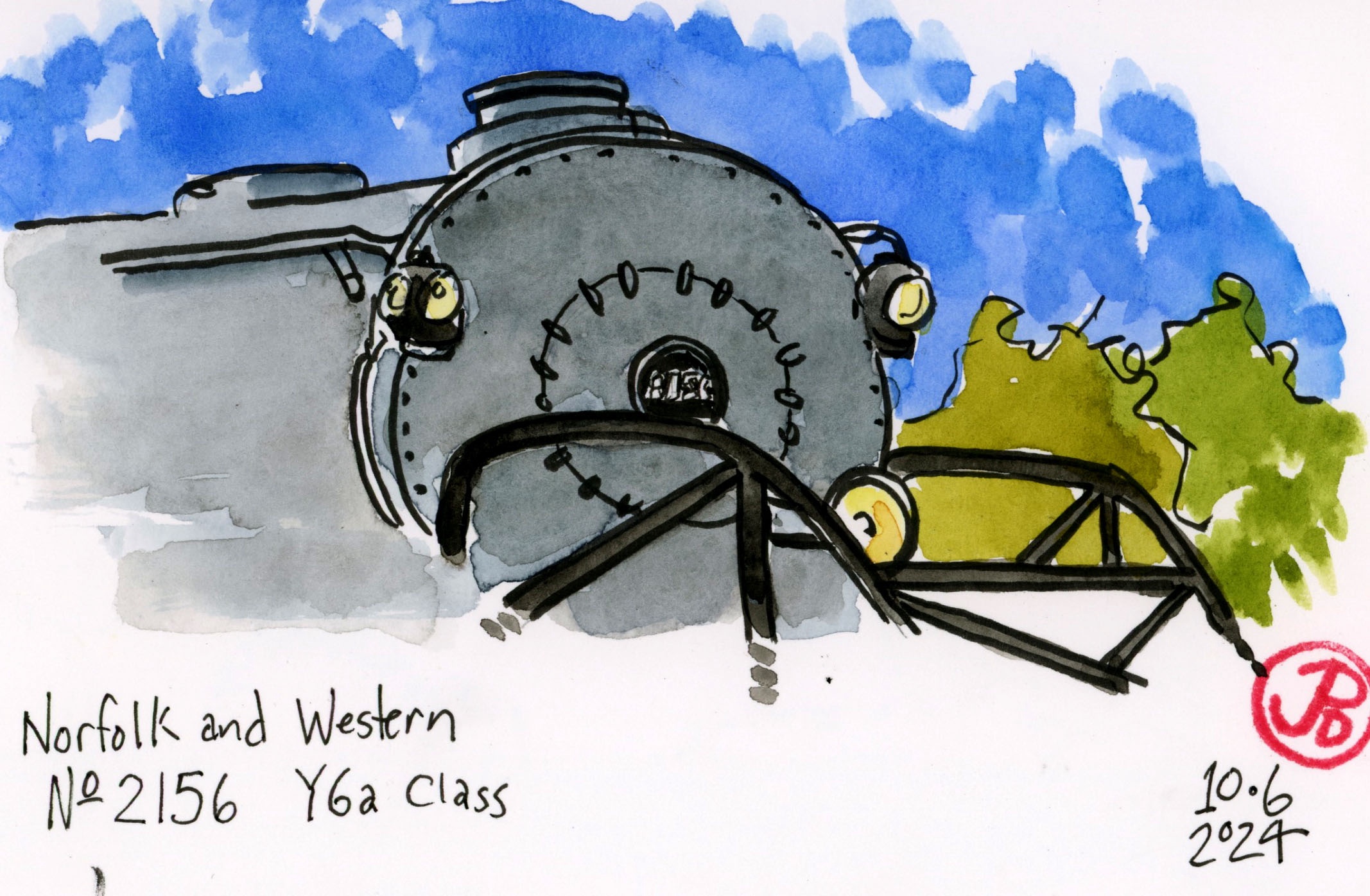

The museum has an amazing collection of large steam and diesel locomotives to sketch. One of those sketches completed the Norfolk & Western triad of A- Class, J-Class, and now Y-Class.

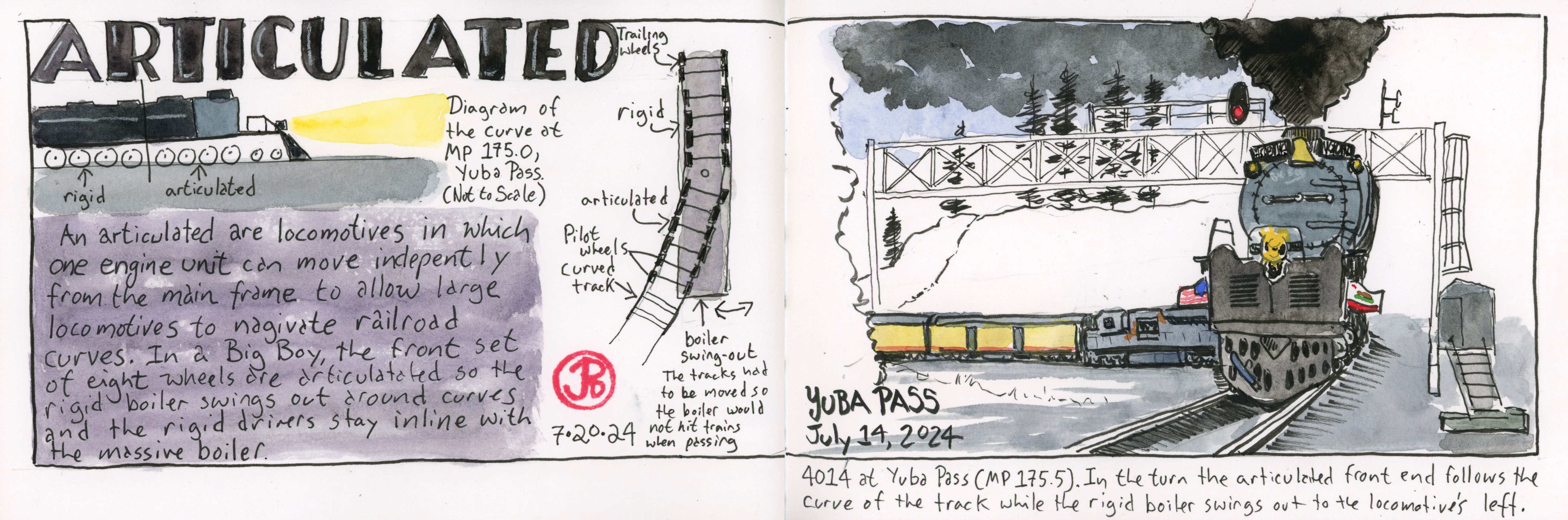

The N & W Y-Class was designed to haul long and heavy coal trains. While it is slightly smaller than Union Pacific’s Big Boys, the Y Class is more powerful than the UP articulated.

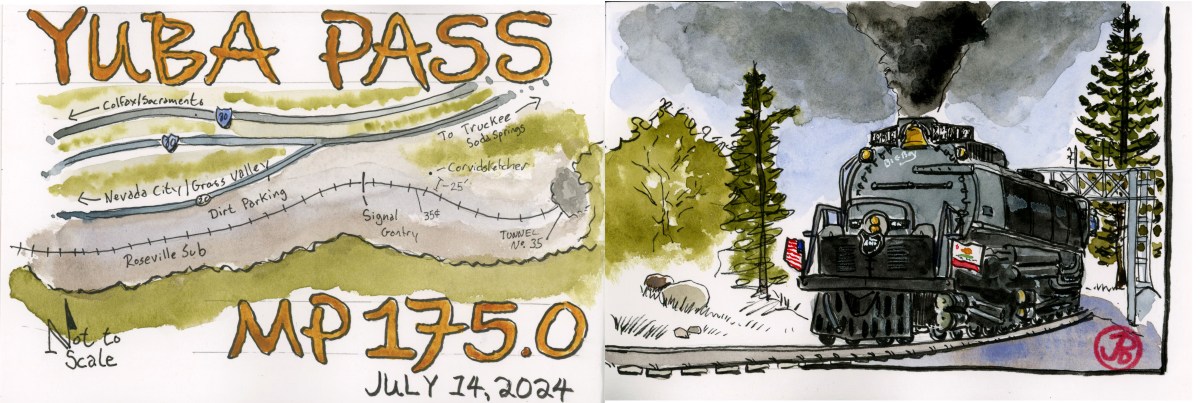

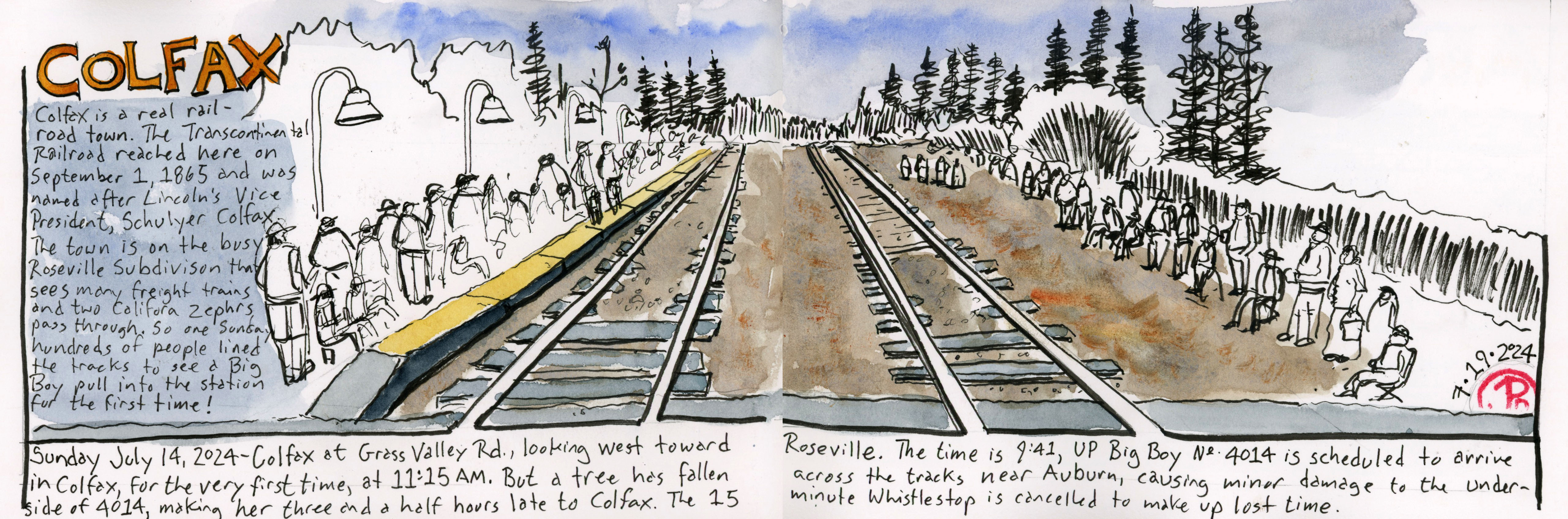

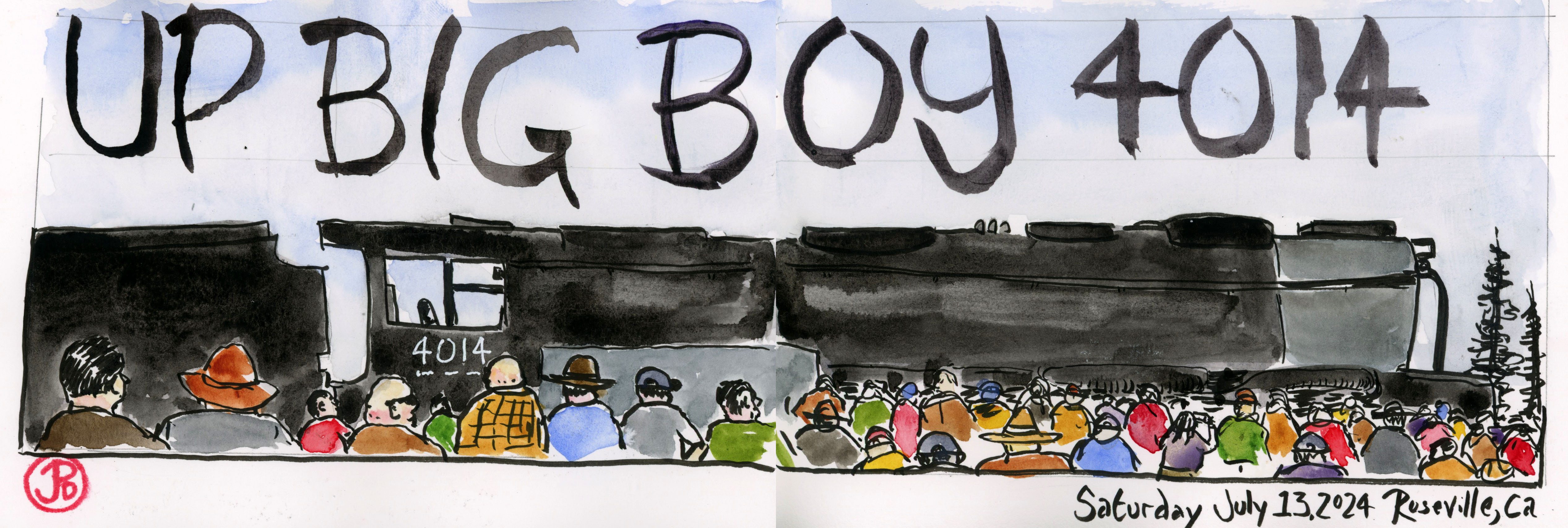

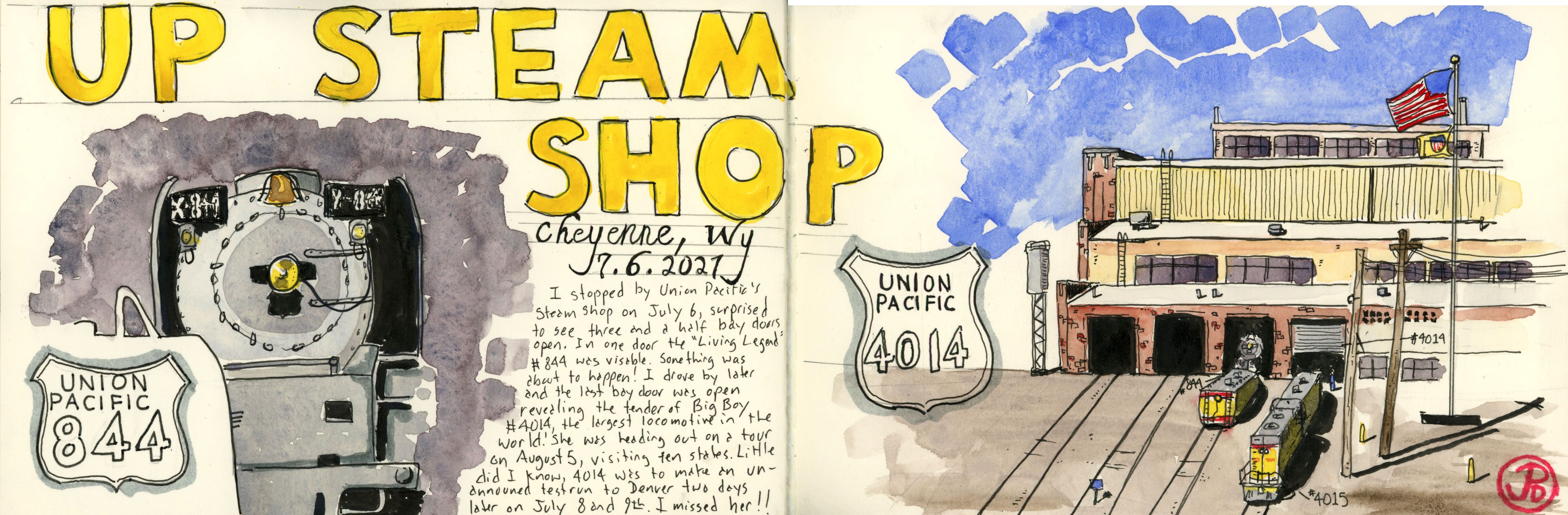

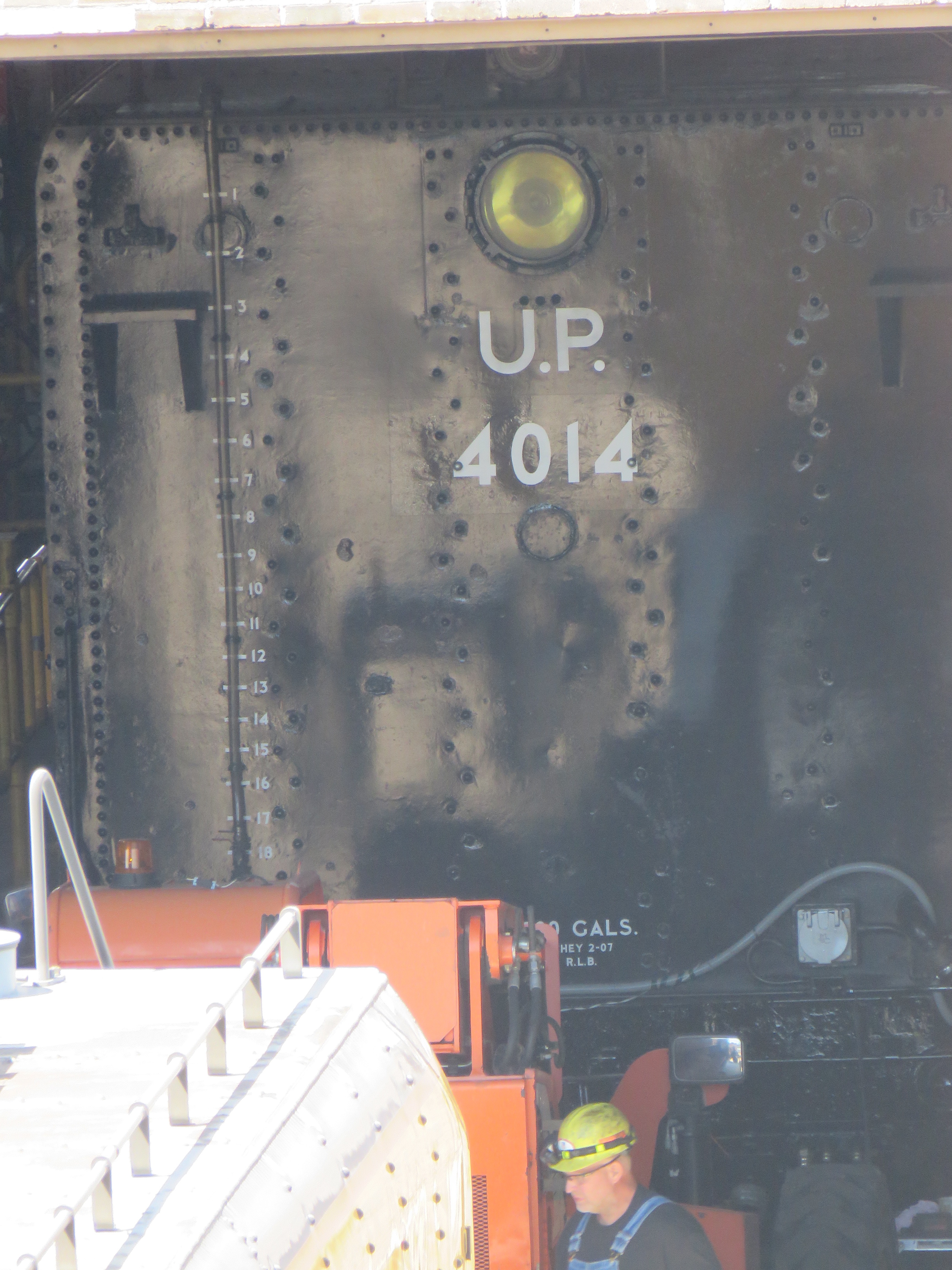

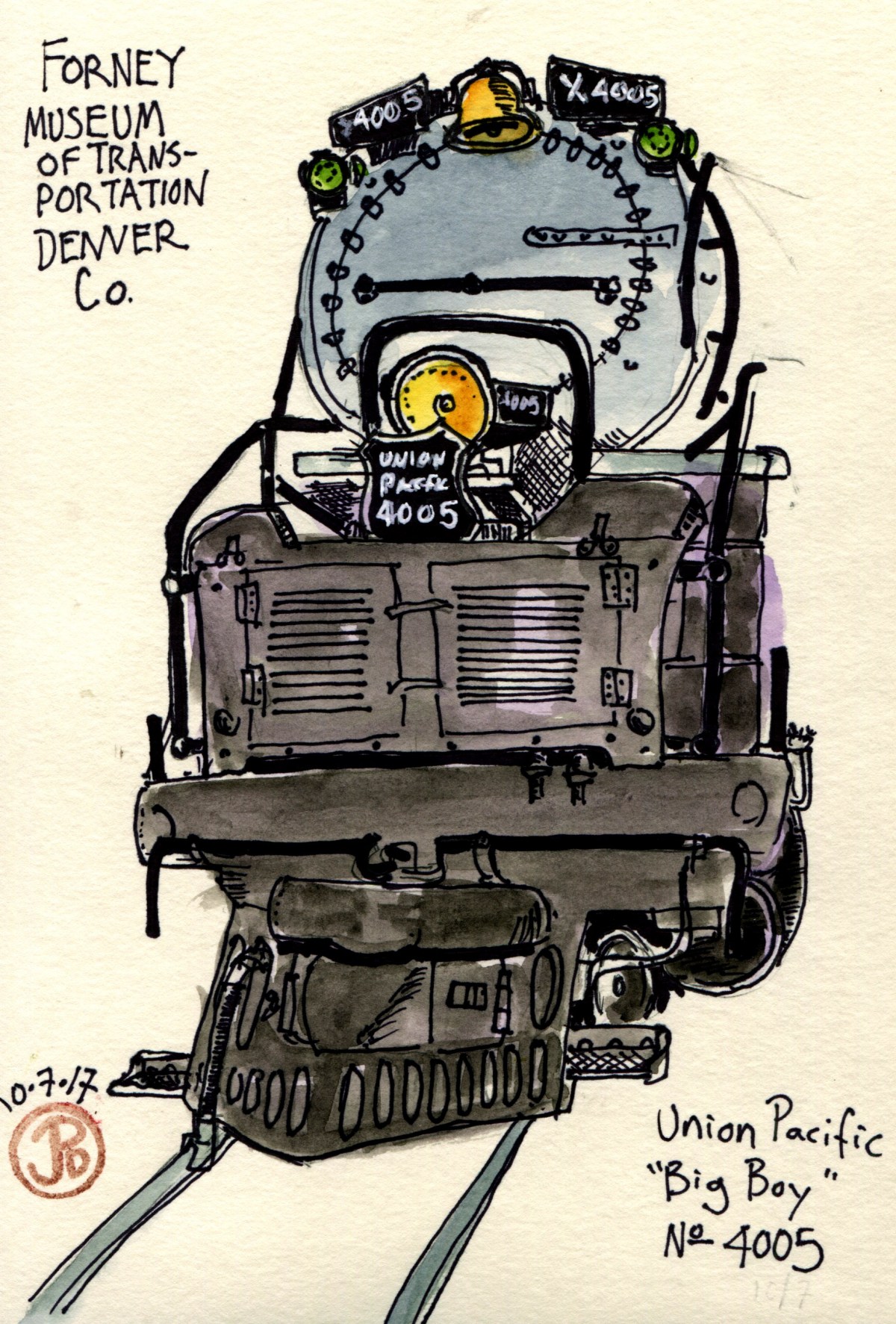

The NMOT is also one of the places to see a Union Pacific Big Boy. I have now seen and sketched four of the eight remaining Big Boys.

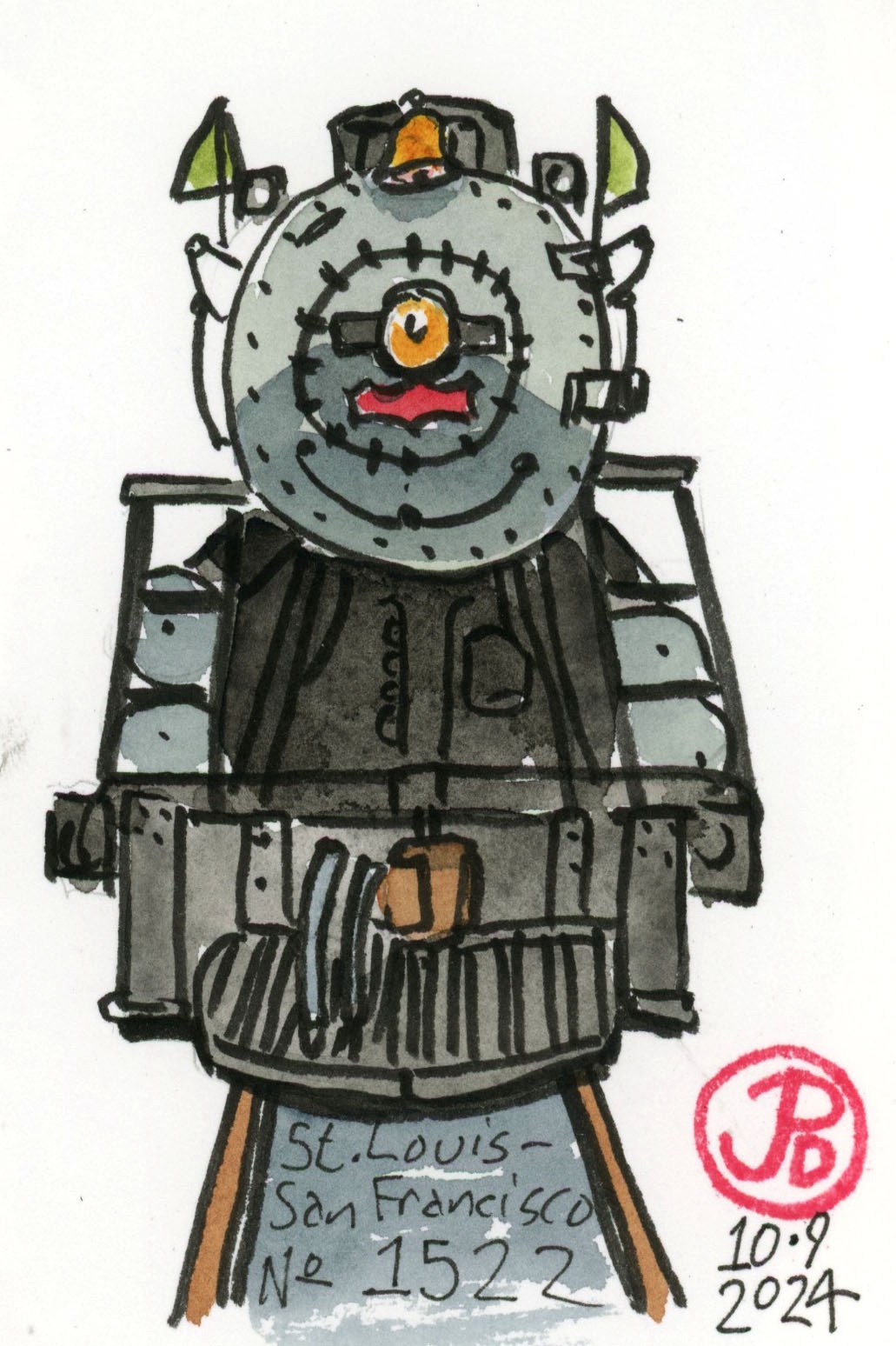

While the Big Boy is a big draw to the museum, there is one locomotive that is the most loved and best known. This is the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway (“Frisco”) No. 1522. This 4-8-2 Mountain type was built in 1926 by Baldwin. The locomotive logged over 1.7 million miles in passenger and freight service. She was restored to working order and was in excursion service from 1988 to 2002 around the Midwest, where many saw and rode behind her.