It is my Christmas Day tradition to wander down to the Central Valley to do some wintering waterfowl birding in the amazing Gray Lodge Wildlife Area, just north of the Sutter Buttes.

The weather forecast told of rain but that wasn’t going to turn me away from seeing the thousands of wintering waterfowl. Besides, the birds don’t mind the rain, they are covered in feathers after all.

I turned off Highway 99, heading west, at Live Oak. The houses soon became fewer and fewer as I made my way from small town to the rural farmlands on my way to Gray Lodge. In the fields bordering Almond Orchard Road I saw one of my expected species: sandhill crane. This is always an amazing bird, a “Birds of Heaven” as Peter Matthiessen called them.

I soon turned into Gray Lodge and I looked out towards the Sutter Buttes and the expanse of water that contained hundreds, if not thousands, of ducks: mallard, American widgeon, pintail, cinnamon, blue-winged, and green-winged teal, bufflehead, gadwell, and northern shoveller. Greater white-fronted and snow geese filled the grey skies.

I started on the auto route. The majority of birding is done by car at Gray Lodge. Your car really becomes a moving blind or hide and as such, doesn’t seem to bother the birds too much.

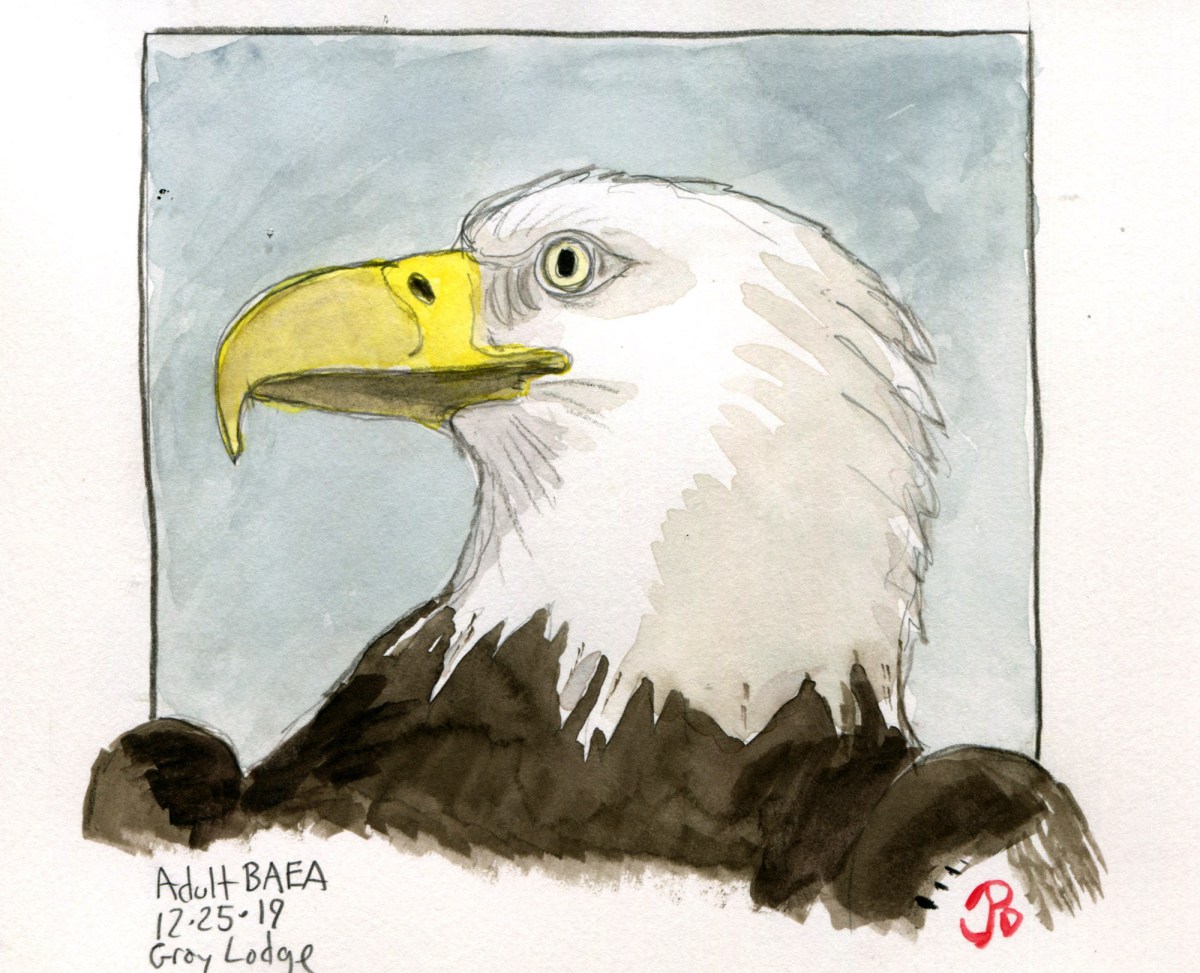

One species that I always look forward to seeing at Gray Lodge is out National Bird, the bald eagle. These large raptors follow the wintering waterfowl and every time they lift off into the air, a mass of ducks and geese rises in their bow wake. I had seen a few far off eagles, perched in trees off to my right. I spotted a few immatures but as I neared them on the auto route, the eagles were jumpy and flew further off over the waters to a tree on the opposite point from where I was.

The unmistakable heft and upright posture of a bald eagle, in this a case an immature. This bird did not allow a close approach. An eagle takes five years to gain it’s iconic “outfit” that most people would recognize: white head and tail, yellow beak, and dark chocolate-brown body.

The unmistakable heft and upright posture of a bald eagle, in this a case an immature. This bird did not allow a close approach. An eagle takes five years to gain it’s iconic “outfit” that most people would recognize: white head and tail, yellow beak, and dark chocolate-brown body.

I came back to the start of the auto route and wanted to take another ride. As I neared one of the parking lots I saw an adult bald eagle flying to my left.

An iconic adult bald eagle flying to my left. Four northern pintails fly above, and probibly away from the large raptor.

The eagle turned towards me and then headed away and landed in the top of a tree with an immature eagle. I raced forward along the route, hoping that the adult would stay.

The adult landed and held it’s wings up as a group of American wigeons take to the air in all the excitement. The immature is to the lower right.

As I moved toward the tree, which was just to the left of the road, the immature took off and headed off. Let’s hope the adult was not as jumpy. Every 20 yards of so, I would angle the car to the right to take a few photos through the driver’s side window.

I finally stopped the car near the base of the tree. The adult was now about 40 yards away. The eagle surveyed the waters and presumably waterfowl, and I was able to enjoy the bird for about 5 minutes. Just as I reaching for my sketchbook and pen bag, the adult flew off across the waters, causing the ducks to lift up into the air and scatter. Now this was my kind of Christmas gift!

An adult bald eagle is distinctive, even as it’s flying away from you. It’s bright white tail is a beacon that tells you what you just missed!

An adult bald eagle is distinctive, even as it’s flying away from you. It’s bright white tail is a beacon that tells you what you just missed!

The unmistakable heft and upright posture of a bald eagle, in this a case an immature. This bird did not allow a close approach. An eagle takes five years to gain it’s iconic “outfit” that most people would recognize: white head and tail, yellow beak, and dark chocolate-brown body.

The unmistakable heft and upright posture of a bald eagle, in this a case an immature. This bird did not allow a close approach. An eagle takes five years to gain it’s iconic “outfit” that most people would recognize: white head and tail, yellow beak, and dark chocolate-brown body.

An adult bald eagle is distinctive, even as it’s flying away from you. It’s bright white tail is a beacon that tells you what you just missed!

An adult bald eagle is distinctive, even as it’s flying away from you. It’s bright white tail is a beacon that tells you what you just missed!