In mid- January, my neighbor from down the hill from my cabin, emailed me that she heard an owl calling, just after dark.

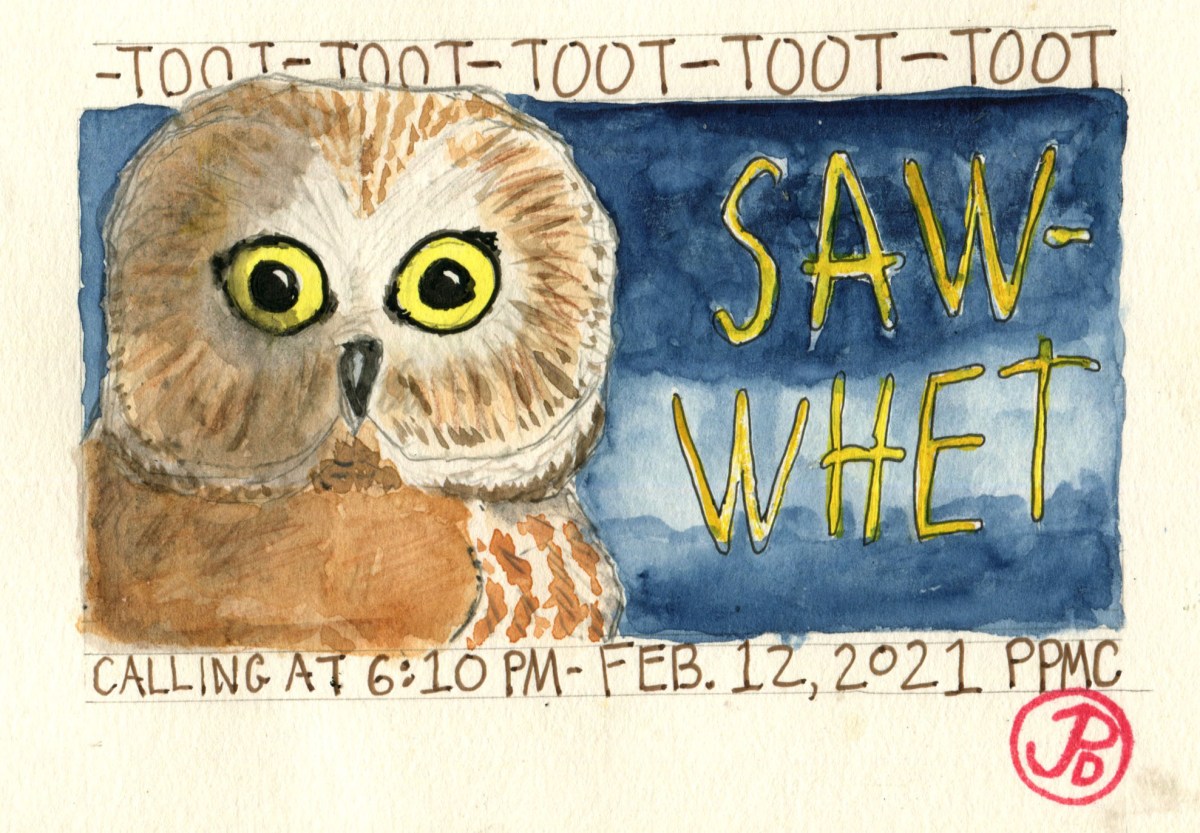

She thought it could be a saw-whet or a western screech-owl. On following evenings the mystery owl called again and again, just after dark. She confirmed that she thought that the owl calling was a northern saw-whet owl (Aegolius acadicus)!

This would be an amazing Santa Cruz County bird to add to my list and especially so to hear this diminutive owl in my own backyard! Well, close to it anyway.

The Northern saw-whet owl is can be common or uncommon resident of the California coast, favoring mixed conifers and deciduous woods. This owl may be much more common than believed because if it isn’t calling, this owl goes undetected. It is one of our smallest owls with a length eight inches and weighing in at 2.8 ounces. In other words, this owl weights as much as three standard sized envelopes.

The northern saw-whet gets its common name because it’s incessant “toot-toot-toot” territorial call that reminded early ornithologists of the whetting or sharpening of a saw; a common sound in the forests as lumberjacks felled trees to fuel a growing nation.

I have never heard a saw-whet call in Paradise Park. This may be because wildlife has been displaced by the destructive CZU Lighting Complex Fire. This fire burned in the late summer of 2020 for 44 days, consuming almost 400,000 acres of the western side of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Some of those animals are now wildfire refugees and are now establishing a new territories.

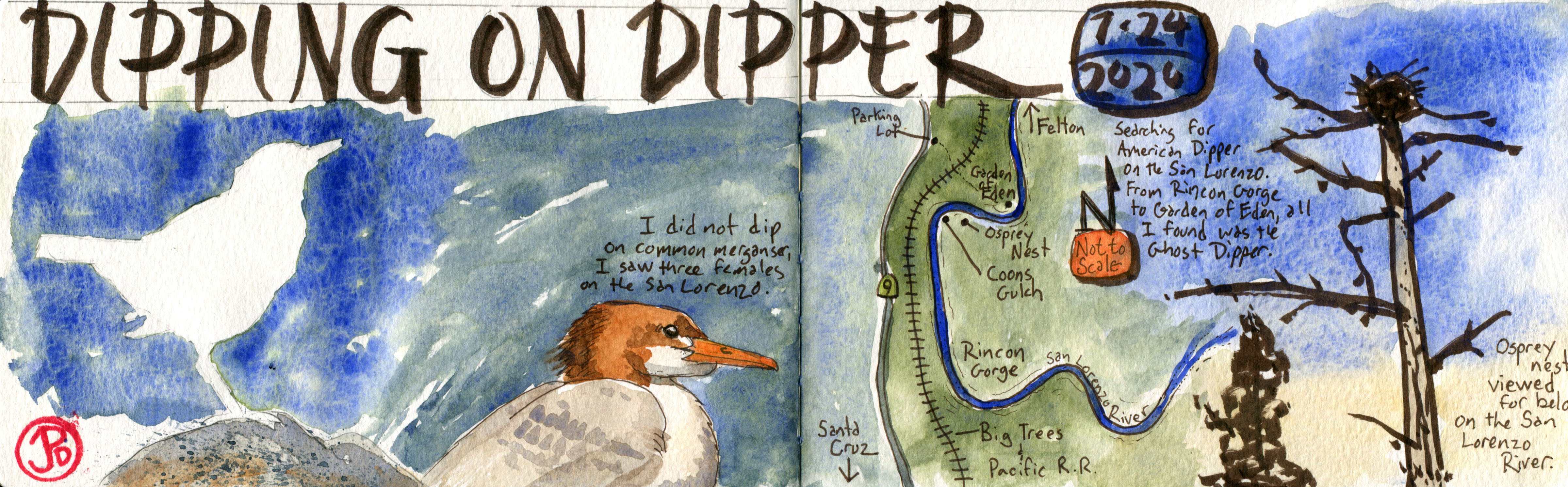

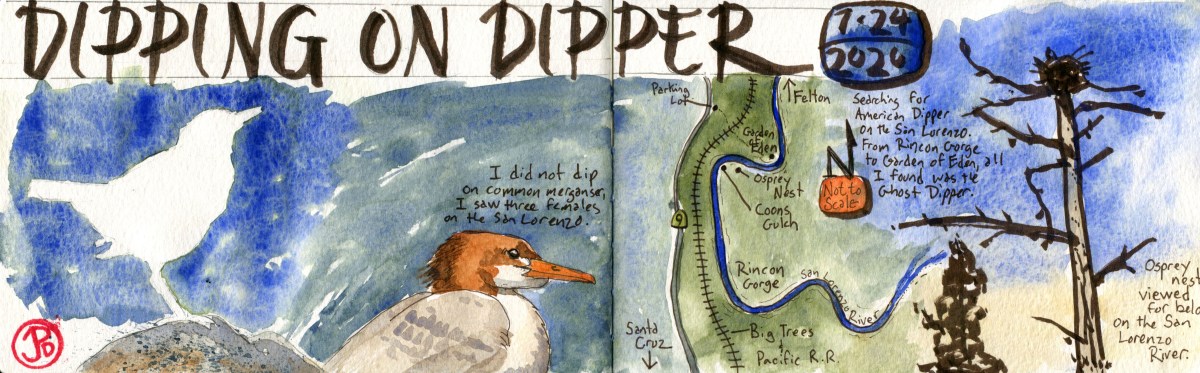

I planned to head down to Santa Cruz and do some owling, to see if I could confirm the existence of a saw-whet in Paradise Park. So I set out at 5:30 PM and walked around as the diurnal birds stopped calling, one by one as they sought out their nighttime roosts. The last diurnal call was the “chip” of a California towhee. It was now time for the night shift.

I centered my search at the picnic grounds. This is where my neighbor had recently heard the saw-whet. Now it was a matter of waiting a time with patience. A time to focusing the senses, to filter out the sounds of traffic on Highway 9 and seek the repetitive toots of the saw-whet.

At 6:10 I heard the first call of the saw-whet. It seemed distant and tough to locate. The saw-whet’s call is very loud for such a small bird, it can be heard from half a mile away.

I moved along the road to try and locate the owl, but as always, owls are elusive. At times it seemed the saw-whet was close and at other times far. As if the owl was frequently changing locations. In reality the owl was probably changing the dynamics of it’s song. It would be silent for a short time and then resume it’s name token song. I now had a new Santa Cruz County bird in my own backyard!

On Saturday evening, I went out for another owling ramble, to reconfirm the saw-whets presence in my world. Would I hear it two nights in a row? I also wanted to get a better sound recording of the owl. The evening before I recorded a faint but distinctive recording.

This time I set out a little later. I was at the picnic grounds at 6:30 pm and it wasn’t long before I heard the saw-whet calling up the hill.

I walked up the road toward where I thought the sound was coming. Hanging from my belt loop was my bluetooth speaker (an indispensable piece of equipment for any tropical bird guide).

I was going to use a recorded call of a call-whet to try to bring the owl closer so I could get a better recording of it’s call. In birding terms this is called using “playback”. When I played the recording through the speaker, the saw-whet seemed to accelerate it’s song. The call was getting louder as if the owl was coming closer to my location.

An owl’s flight is silent so I could not hear if the saw-whet was flying towards me. But what I did hear was the owl’s wings brushing against the branches above me. I was able to get two recordings with my iPhone and then I left the saw-whet to it’s “day”of establishing it’s territory and hunting for small rodents.

Here is a link to my eBird checklist with the two recordings I made: https://ebird.org/checklist/S81289488

I headed back to my cabin, satisfied with my night revels but I had one last trick up my sleeve. I stopped outside my neighbor’s house and I turned my bluetooth speaker on and played the saw-whet call at full volume! Within a minute, she came out surprised that it was just me and not a saw-whet. I thanked her for telling me about the saw-whet owl in our backyard!