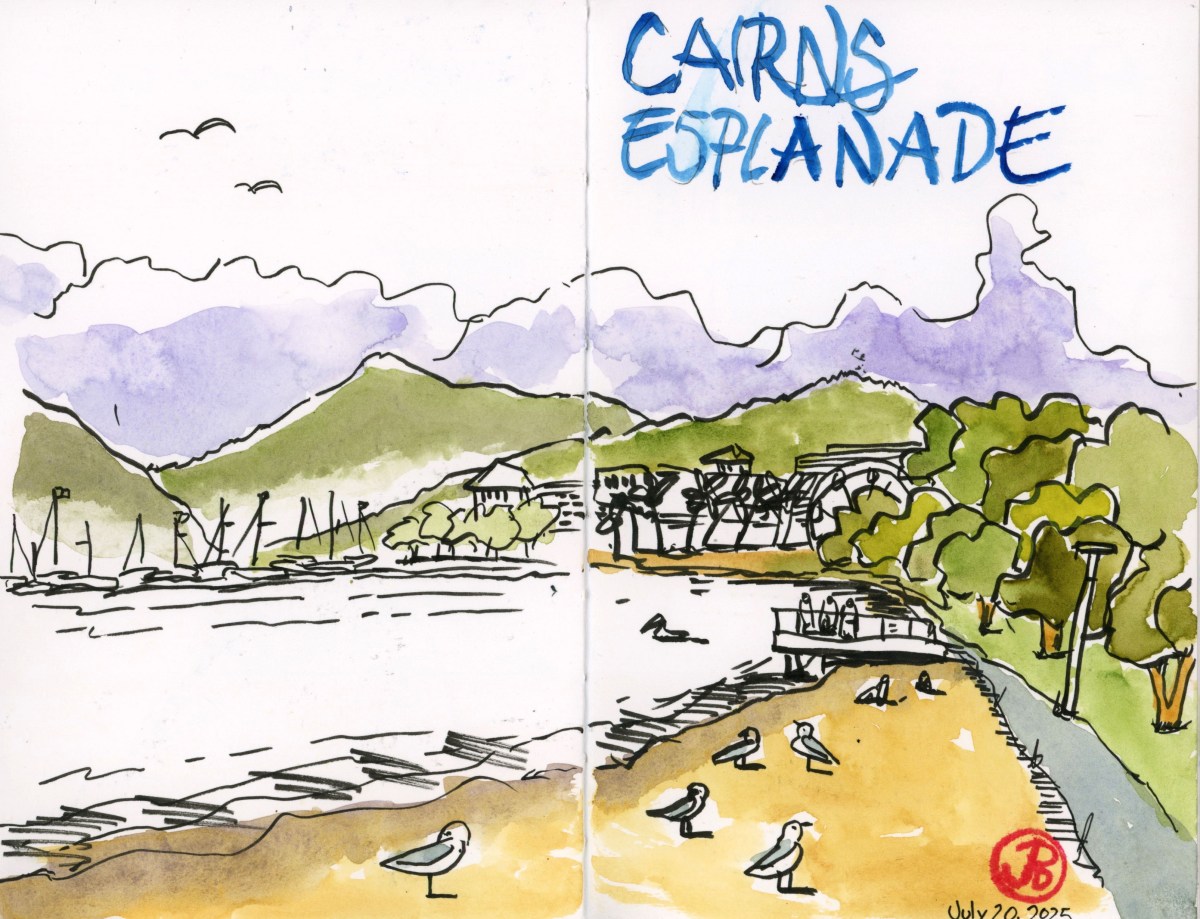

The top birding site in the Australian State of Queensland is the Cairns Esplanade.

The esplanade is a path that runs north to south along the water with parks and trees bordering to the west. This path is popular with joggers, bikers, and dog walkers, as well as birders from around the world.

When the tide is right, many waders feed close in on the exposed tidal flats but there are always birds to be found foraging in the trees.

With the following sketches I highlight a few of the species I encountered on the Esplanade. While none of these species are rare or Esplanade specialties, they are birds that grabbed my attention.

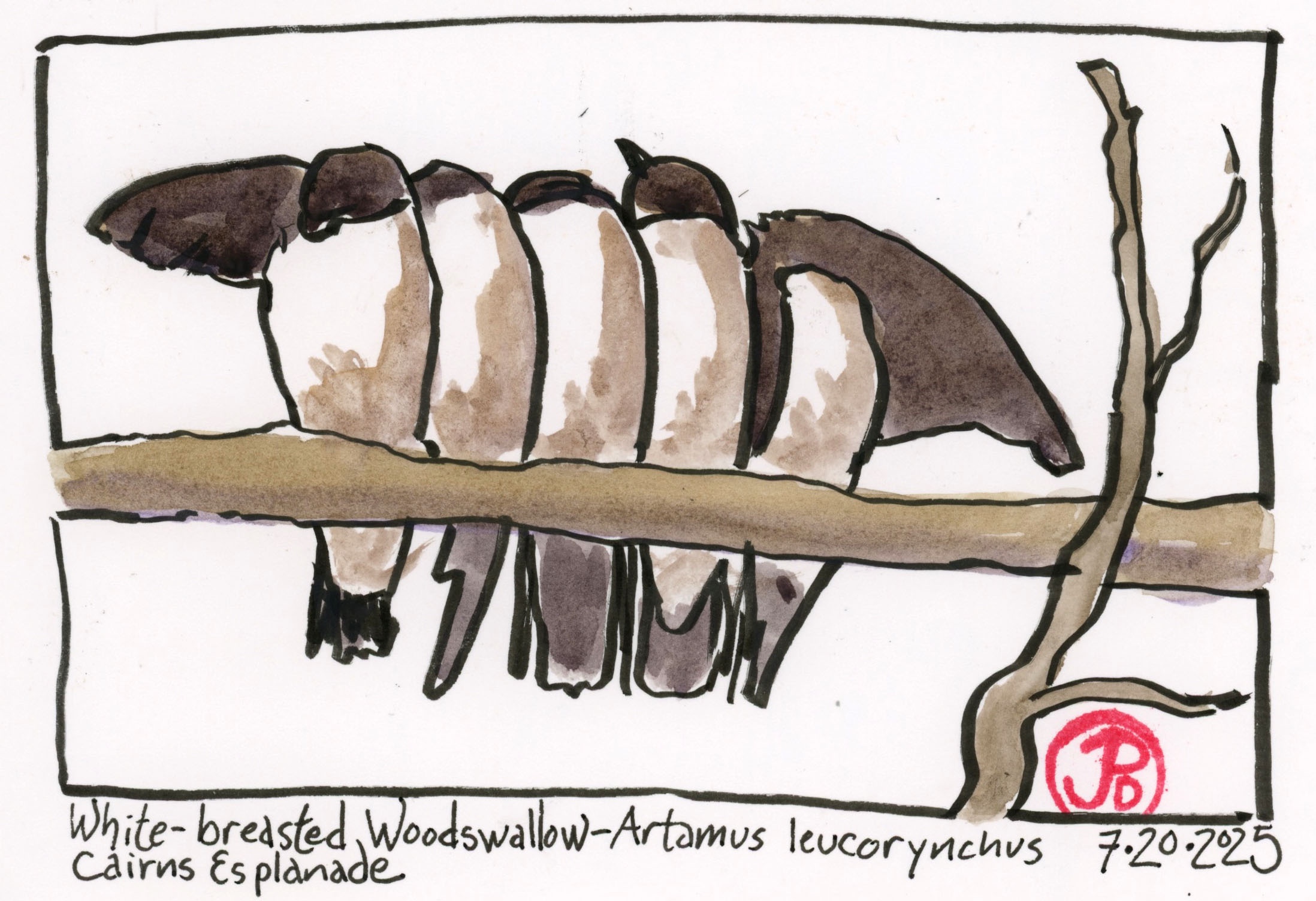

Ever since seeing woodswallows in my Australian bird guide I knew I wanted to see them, primarily because of an interesting behavior. My guide reads, “compulsively social when loafing or roosting, often settling in tight rows on branches to sleep or to preen themselves or each other”. There are six species of woodswallow in Oz, these were white-breasted.

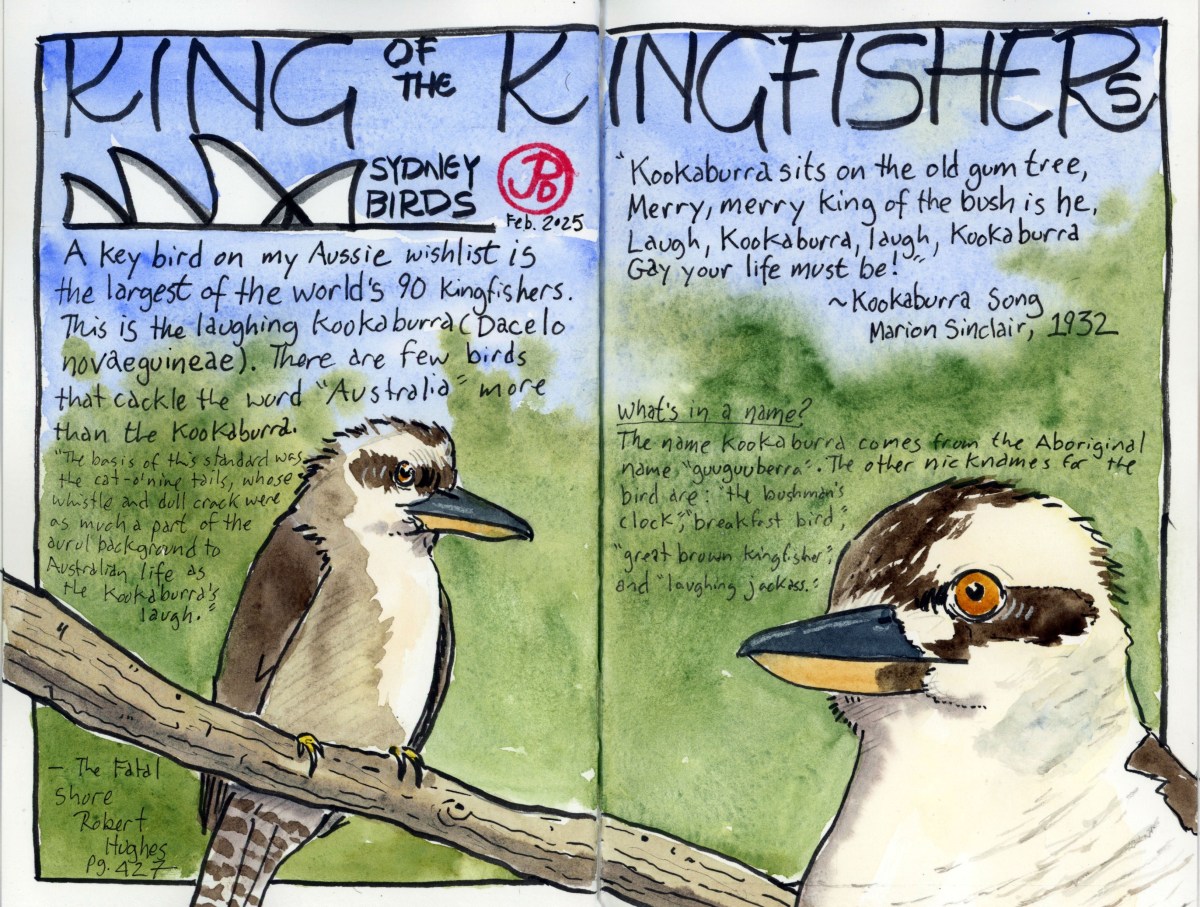

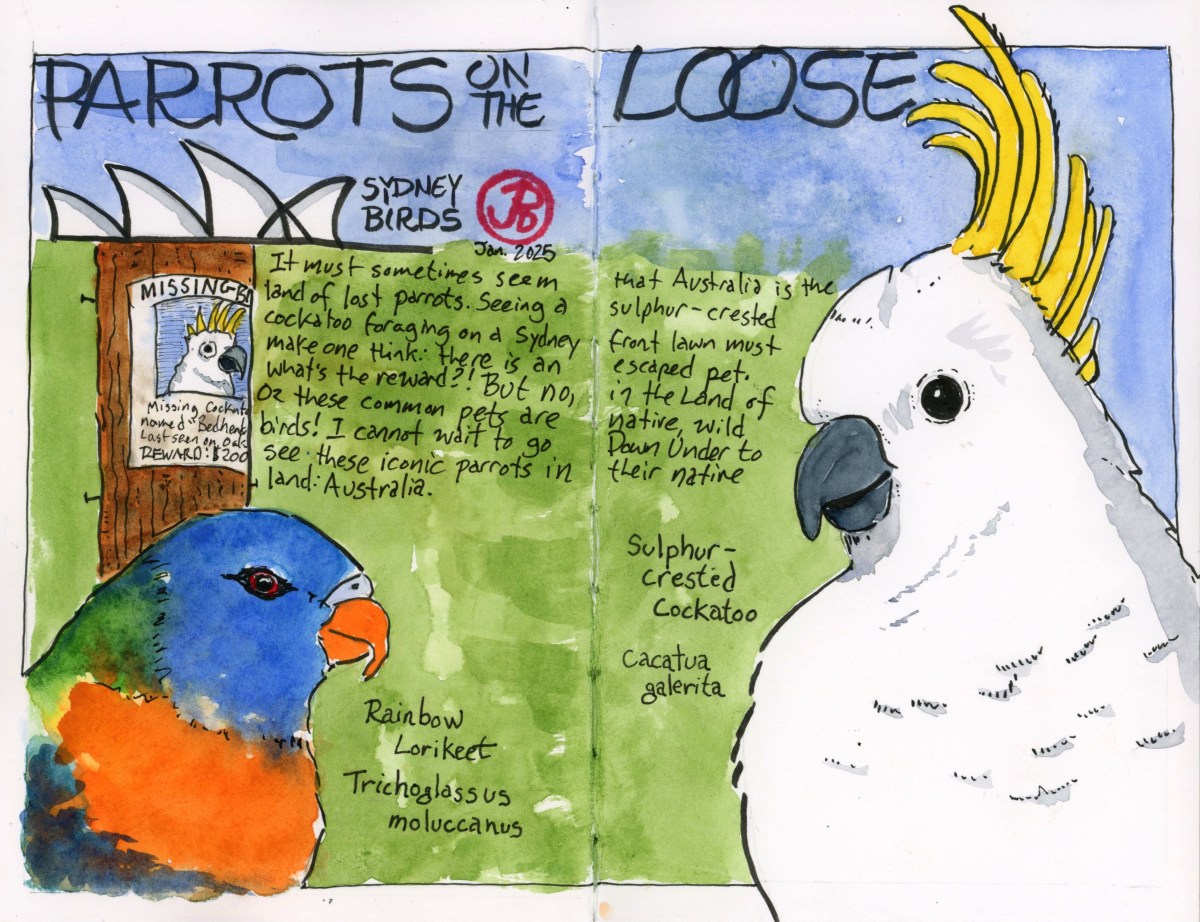

While in Australia I added seven species of kingfisher to my world list including the world’s largest kingfisher, the laughing kookaburra. I added my last species of kingfisher on my final day in Cairns birding the northern Esplanade.

In my bird guide it is known as the collared kingfisher but is now known as the Torrisian kingfisher. Named for the Torres Strait which is the body of water separating Queensland and New Guinea.

I had missed this larger kingfisher on two other visits. The most common kingfisher on the tidal flats and in the trees was the wonderfully named scared kingfisher.

On my last pass I found two Torrisans perched in trees near the water. They were both calling and having me stunning looks in the morning light!

The final bird that I am highlighting is perhaps the most common and as one bird guide notes, “widespread and well-loved”. And I certainly loved my encounters with the Willie wagtail.

The wagtail seems to relish being in the presence of humans. While I was walking across a lawn at the northern end of the esplanade, a Willie wagtail flew up to me and landed close. The bird followed me as I traversed the grass and I realized the wagtail was using me like the cattle egret uses cattle, as a way to scare up bugs from underfoot.

I had experienced this behavior once before, as I was being followed Wunce by a barn, swallow, while I was crossing a soccer pitch.