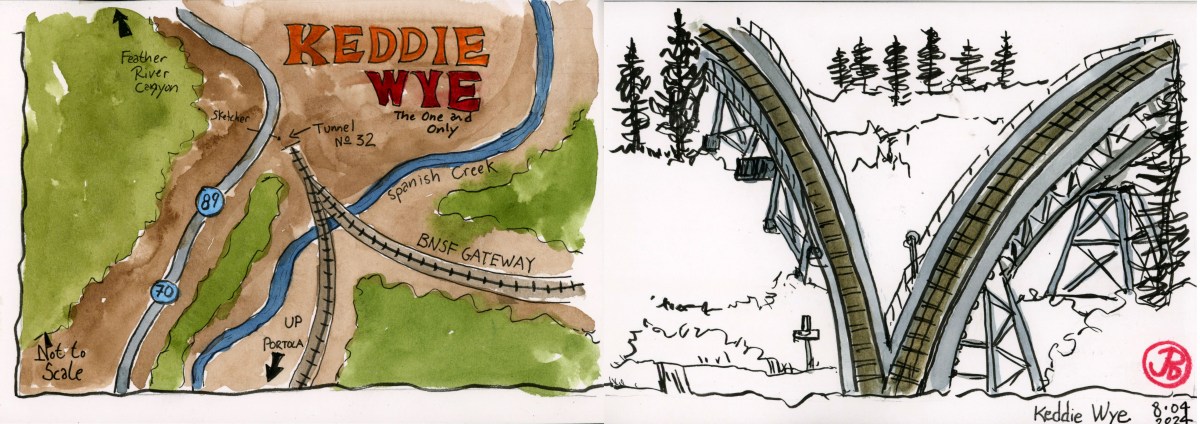

One of the Seven Marvels of the Feather River Route is to be found a few miles north of Quincey.

The Feather River Route, also known as the Canyon Subdivision, stretches between Oroville and Portola, Ca and competed with Southern Pacific’s route over the Sierras at Donner Pass.

The Marvel is known as the Keddie Wye. This is where two tracks comes together to form one track, looking like the letter “Y”. Now this in itself isn’t much to write home about but when both sides of the “Y” are on trestles above a creek that joins together before entering a tunnel and then you know this is a special piece of railroad engineering.

The two forks of the “Y” are also where two different railroads meet. On the right is the former Western Pacific Railroad, now Union Pacific, and one the left is the BNSF (Burlington Northern and Santa Fe).

After about a 45 minute drive from Portola on Highway 70, the famous Keddie Wye appeared to my right. I pulled over and found a vantage point to sketch. I perched on a narrow trail above Tunnel No. 32 looking out to the two forks of the wye.

Now the only thing missing was a freight train. It would have been nice to see a train traverse one side of the “Y”. As I was told at the Western Pacific Railroad Museum, Sunday is a quiet day on the high iron.

After my sketch (right side of the spread), I headed down Highway 70 into the Feather River Canyon proper. The Highway parallels the railroad and the Feather River. This is a beautiful drive and I periodically looked off to left at the rails across the river. No trains.

I was about 20 minutes from the wye when I heard the screech of steel wheels on rail. I looked to the left and a Burlington Northern and Santa Fe (BNSF) was climbing up the canyon with a mixed freight consist.

I found the nearest pullout and then reversed direction as I chased the BNSF up canyon. I wasn’t going to miss the freight on Keddie Wye!

As I climbed up Feather River Canyon I kept an eye to my right for glimpses of the train. I should have no problem overtaking the train as the line speed limit was 25-30 mph.

I soon came to the end of the train and before long I was approaching the five bright orange diesels on point. I passed them with time to spare.

Once I reached the wye I reversed direction again and parked at the pull out. I figured I was about ten to fifteen minutes ahead of the freight and I took my position on the narrow path above Tunnel 32. Now I had to just wait, wondering if I would be able to hear the approaching freight from my position.

Within ten minutes I could hear the diesels working up grade and the first locomotive appeared below me. The train headed onto the left side of Keddie Wye onto the BNSF Gateway heading north towards Lookout and Klamath Falls.

What a memorable experience to see a piece of railroad history that is not a static museum piece isolated in time but in use today.