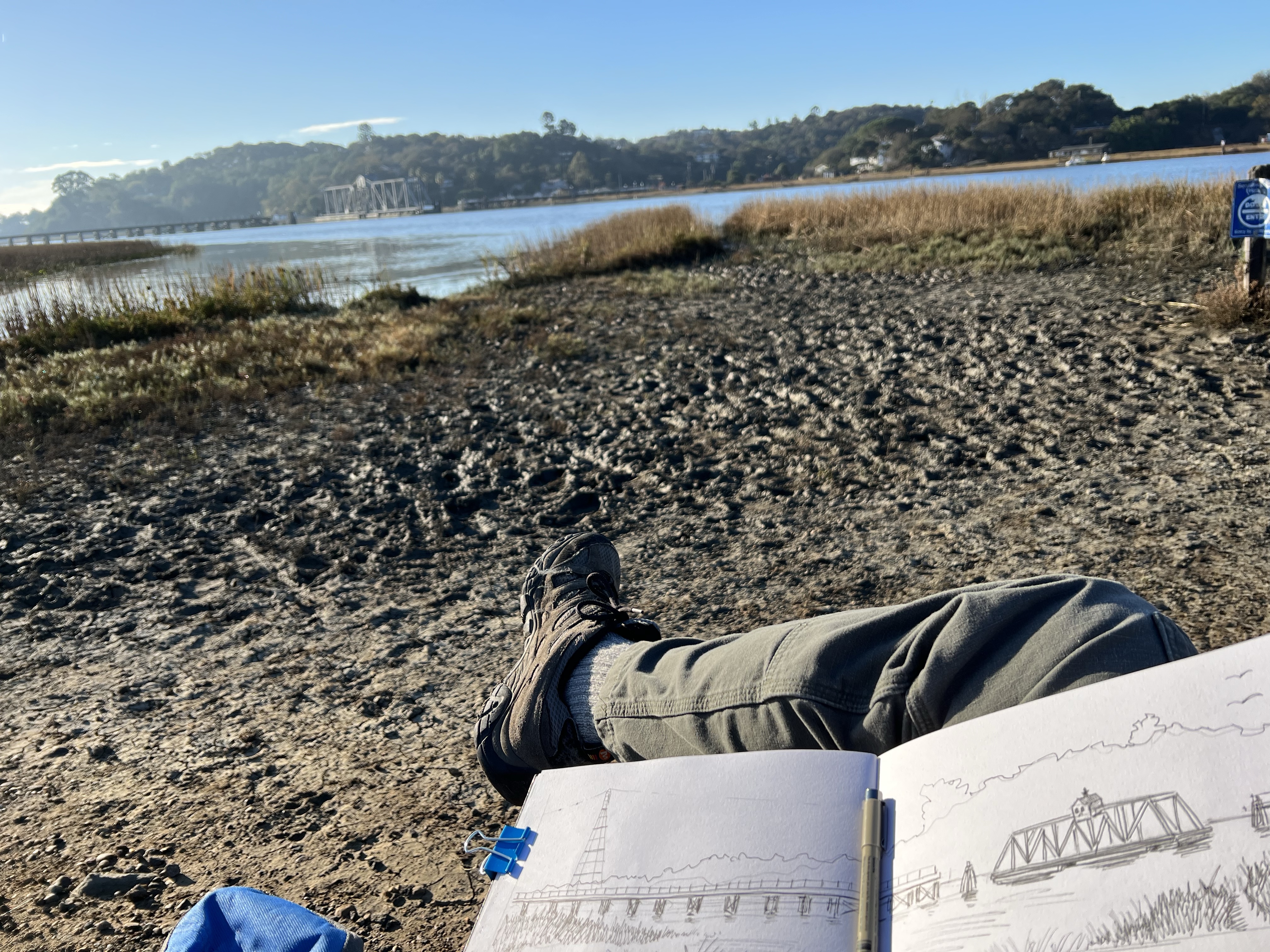

Grasshopper and I headed down south to the county of my birth (Santa Clara) to sketch in it’s biggest city (San Jose). Our destination was in Kelly Park: the San Jose History Museum’s History Park.

This open air museum has a collection of about 30 historic buildings, some original and others replicas. Streetcar tracks run down the streets and on weekends, a vintage street car operates. What drew my attention was a train (of course!)

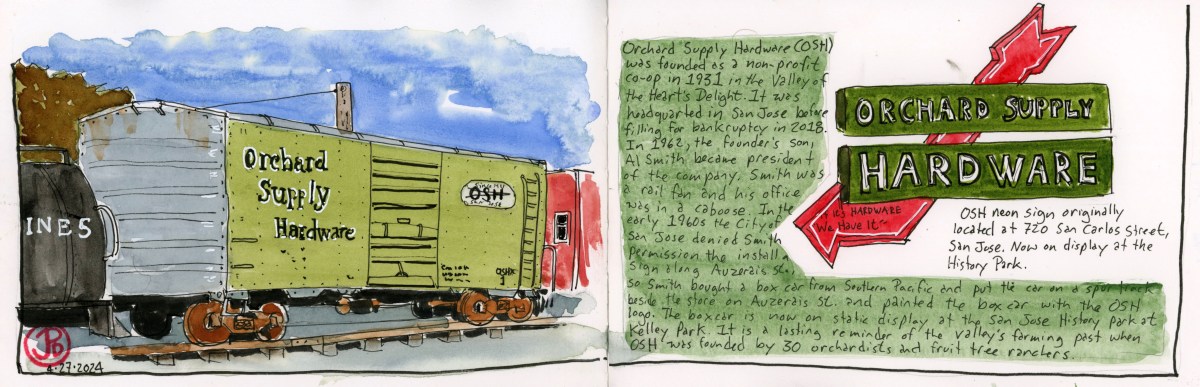

On a set of tracks is Southern Pacific 0-6-0 switcher No. 1215 attached to a consist of a green boxcar, and a SP bay window caboose (No. 1589). What attracted my sketching attention was the green boxcar with the words “Orchard Supply Hardware” painted on the side.

Orchard Supply Hardware or OSH was founded as a co-op in 1931. Its founders were 30 farmers, mainly orchardists and fruit tree ranchers.

The name “Orchard Supply” harkens back to the time when Silicon Valley was then called the Valley of Heart’s Delight and was covered in apricot and cherry orchards.

Growing up in the 1970s in Sunnyvale, our house was built on a former apricot orchard. We even had a remnant tree in our backyard. There were still orchards on the edges of housing developments. The agrarian past, back then, did not seem so far away. Now it has all but disappeared.

OSH was part of my childhood. The second president, Al Smith, was a huge rail fan. He even had his office in a caboose. Starting in 1975, each year OSH would put out a calendar with paintings of trains. There was always one in our household.

In the 1960s Smith petitioned the city of San Jose to install a sign for OSH but he was denied. He did not give up. Instead he bought a boxcar from Southern Pacific and put it beside one of his stores on a rail siding. He then painted it bright green and painted “Orchard Supply Hardware” in big letters. This boxcar is now in the History Park along with a 1950s neon sign for the store. I sketched both (featured sketch).

After sketching the boxcar and neon sign we walked around the park looking for a new perspectives.

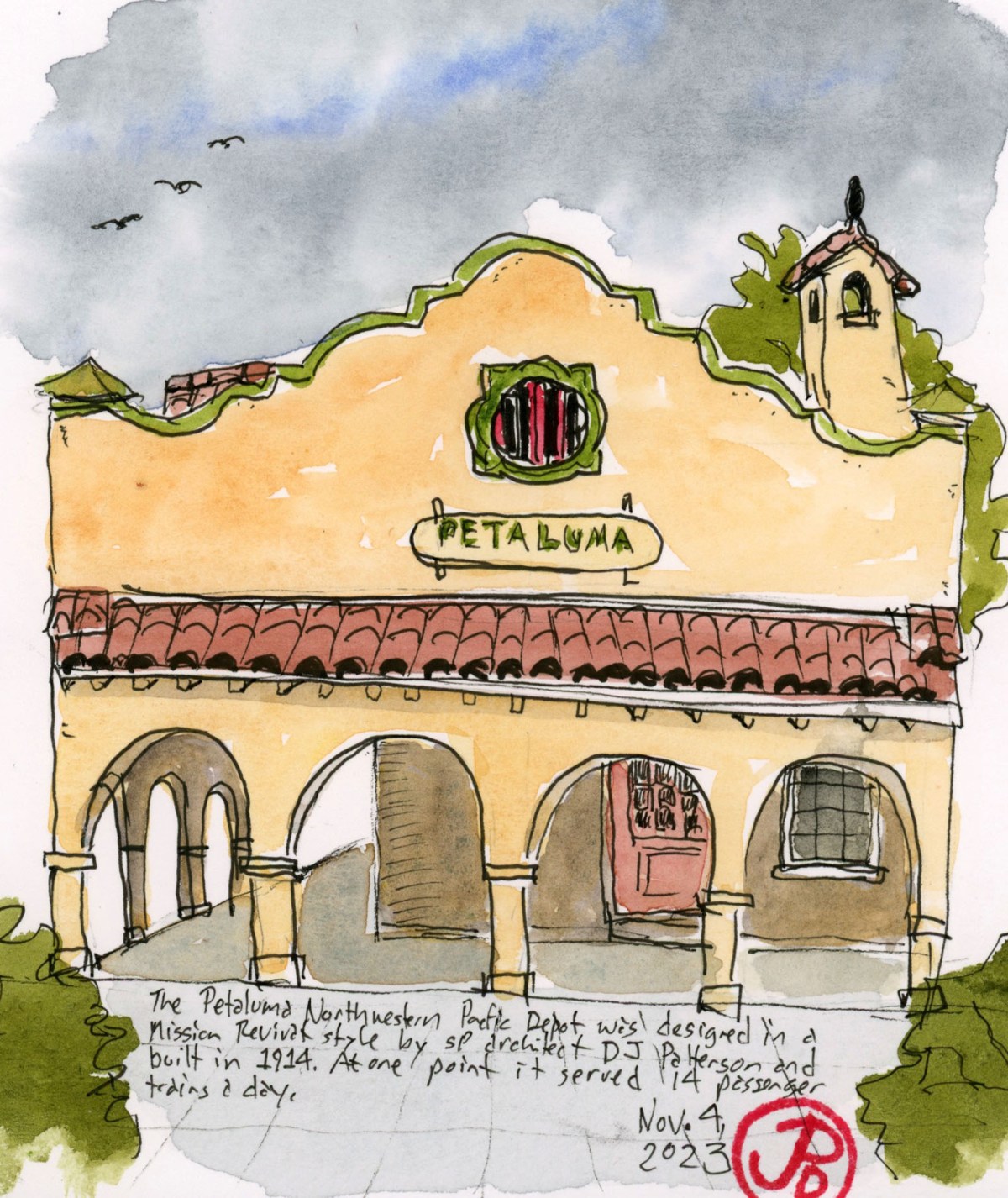

I chose to sit across the street from the replica of the Pacific Hotel. In the background is a half-scale replica of San Jose’s Electric Light Tower. The original 1881 tower was 237 feet tall. In 1915, the tower was damaged in a windstorm and it later collapsed.

While I was sketching I struck up a conversation with an elderly volunteer who had been volunteering at the museum for the past 20 years or so. We reminisced about the valley’s yesteryears (am I really that old!!) and we reflected on the changes to the South Bay. During our conversation I was well aware that it was volunteers like her that keep the hidden history from disappearing forever.

And she is a retired teacher, but of course she is keeping fleeting history alive! That’s just what teachers do.