My return journey was a beautiful but a somber one.

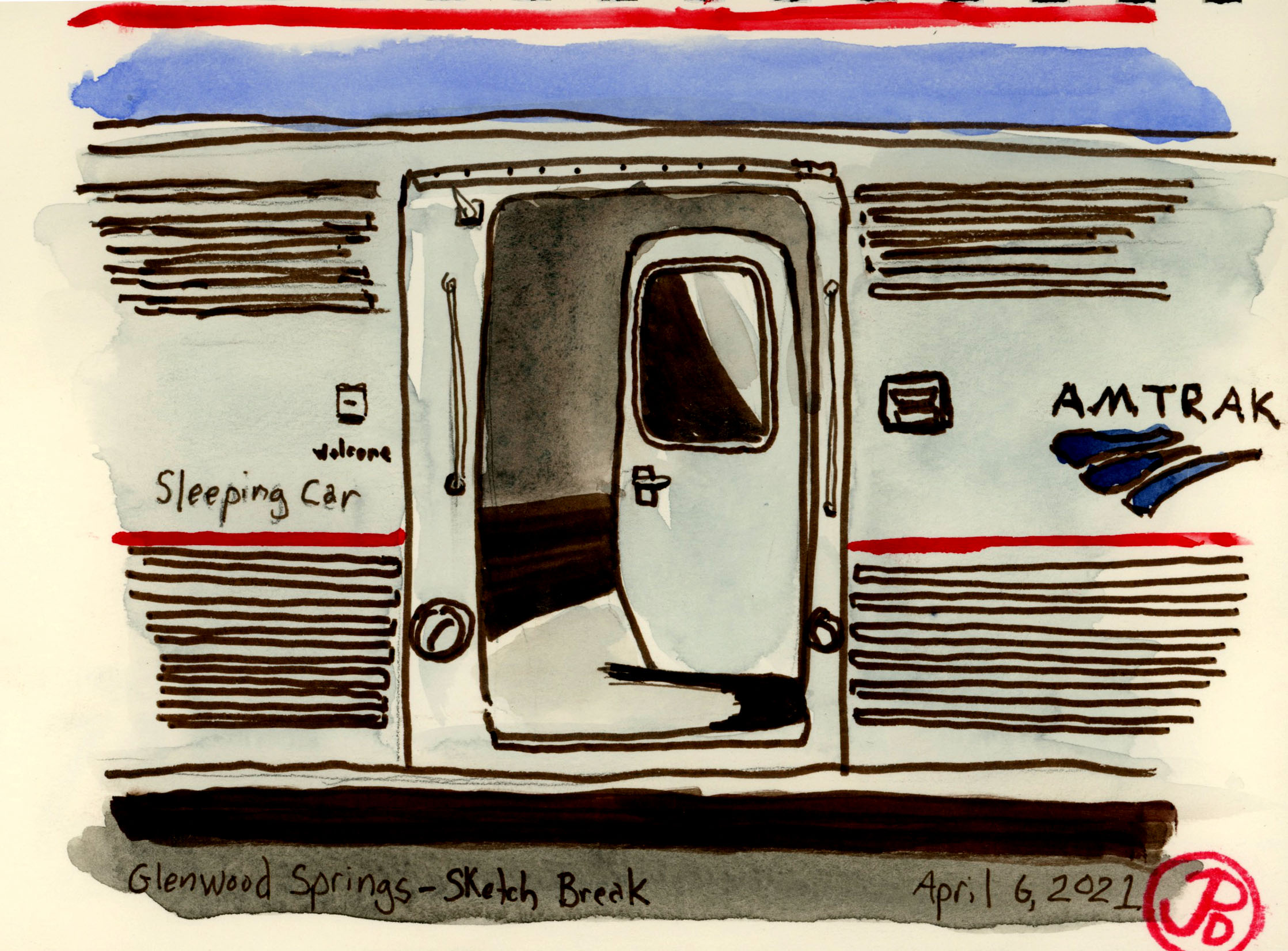

I spent much of my time in my roomette with short trips to the dining and observation car.

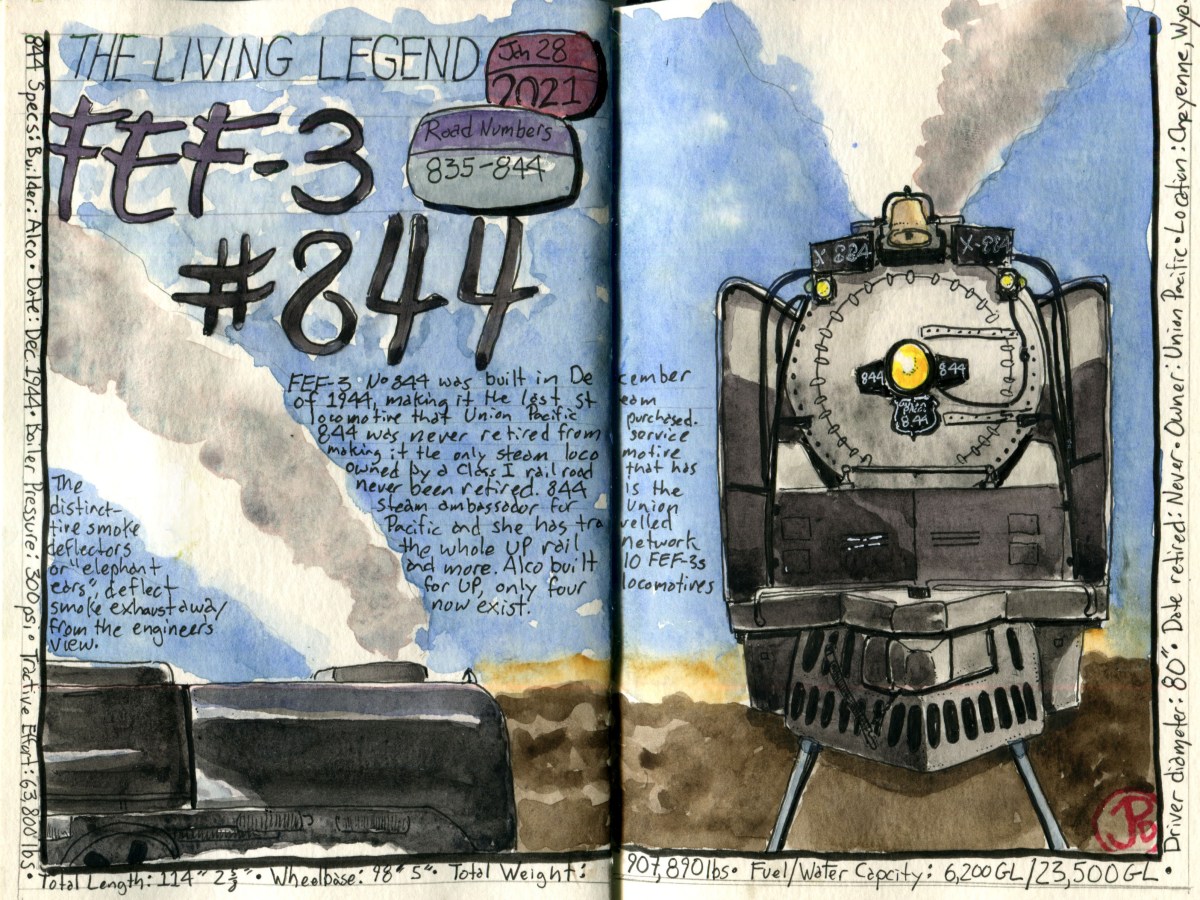

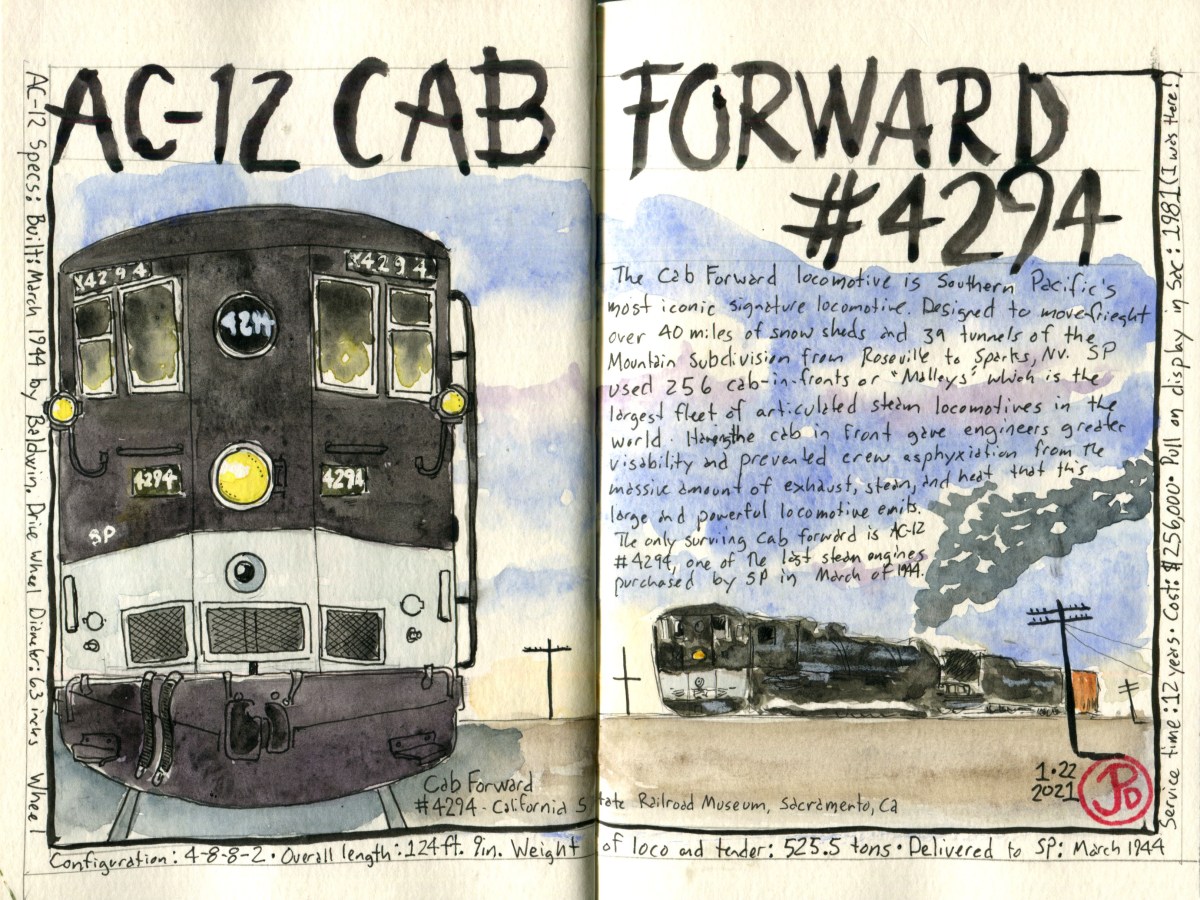

Taking the train back gave me the chance to reflect on the almost 47 years of my brother’s life. I lost myself in the landscapes and continued to sketch during our brief “Sketch Breaks”. Sketching provided the focus and “in the moment” experience my soul needed. Sketcher therapy I suppose.

One other activity that kept my mind busy was train birding. I created a list of all the birds seen from the train, without binoculars. I tallied 43 species as well as six mammals including elk and bighorn sheep. A highlight was having an adult bald eagle keeping pace with the Zephyr while we followed the Colorado River in Utah.

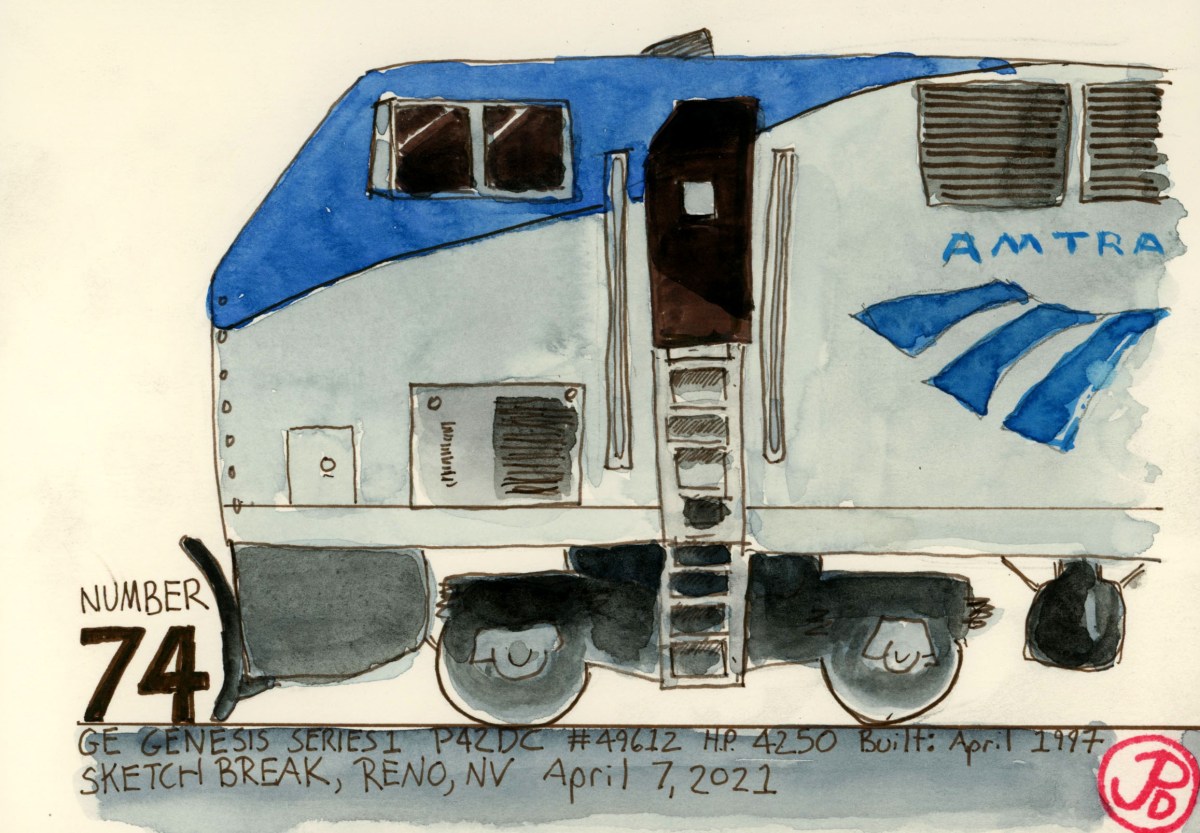

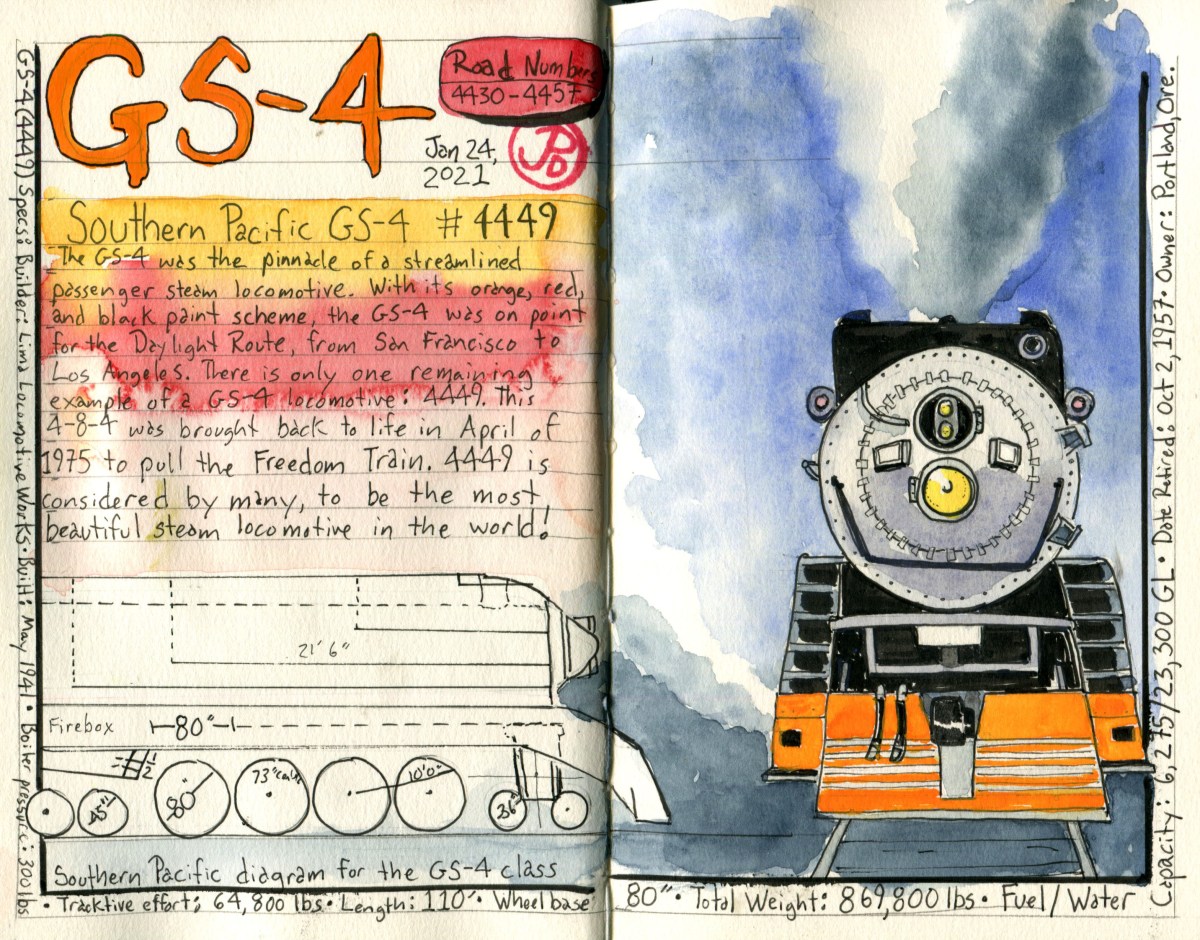

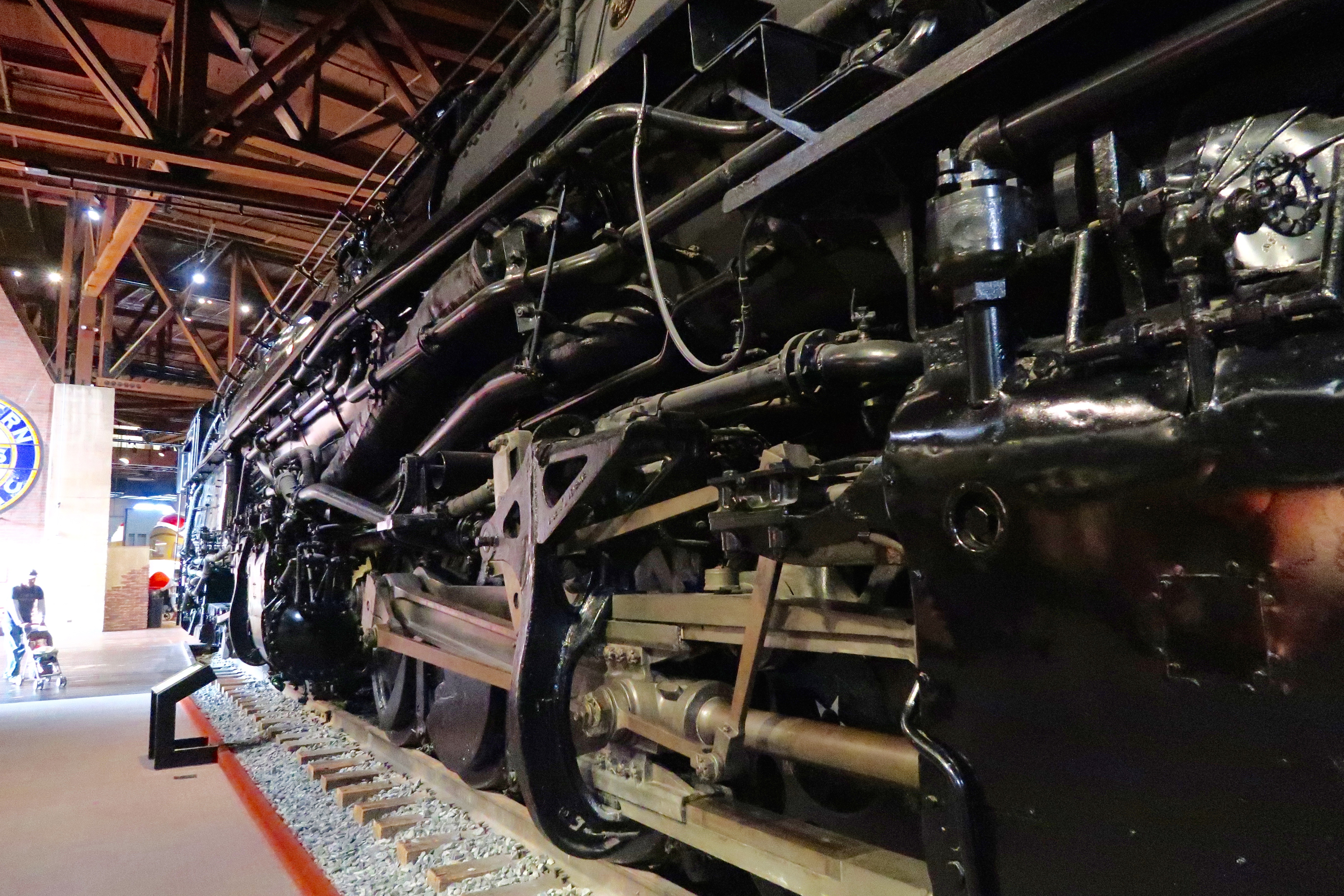

In Reno, the Zephyr pauses for a little longer than most stops because there is a crew change. This is when the engineer is replaced by a fresh one. During this time I sketched the profile of the locomotive on point, a General Electric P42DC, built in April of 1997. In an uncanny instance of coincidence, the locomotive number is 74, my brother was born in 1974. This seems to be the perfect locomotive to lead me back home to my mother.

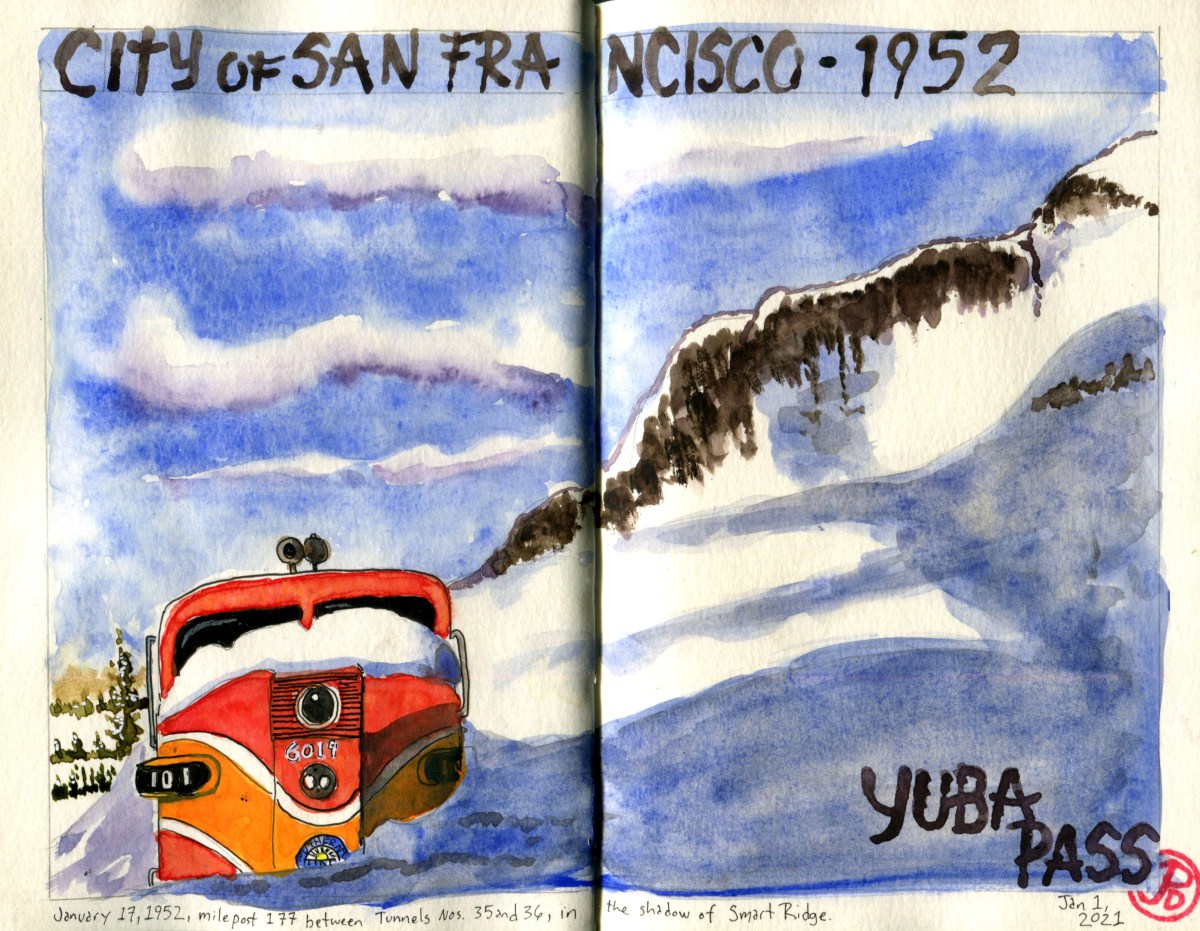

In Truckee, I called my mom to let her know that California Zephyr Number 5 was running on time. This was going to be the first time I had seen my mom since learning if my brother’s passing. I suppose that I could have booked a last minute fight from the Mile High City to be there much sooner but the pace, the landscape, and the rocking lullaby of the Zephyr seemed to be the right choice for taking me back to California.

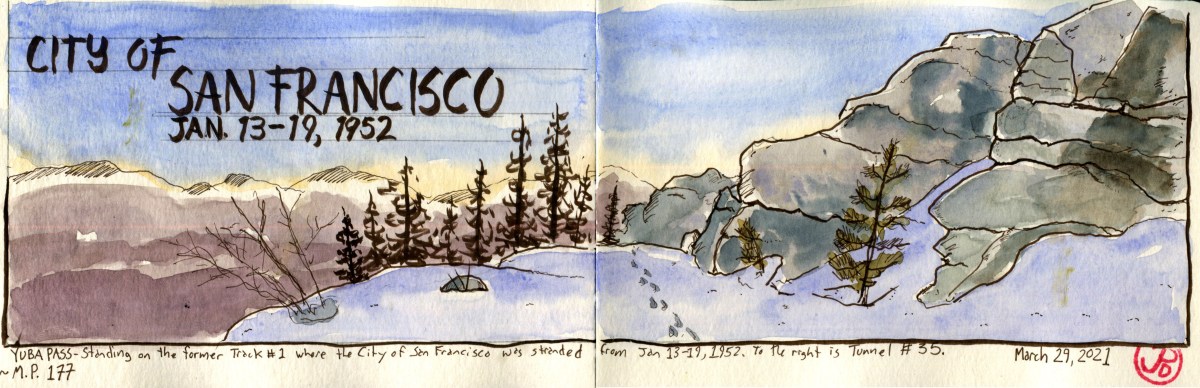

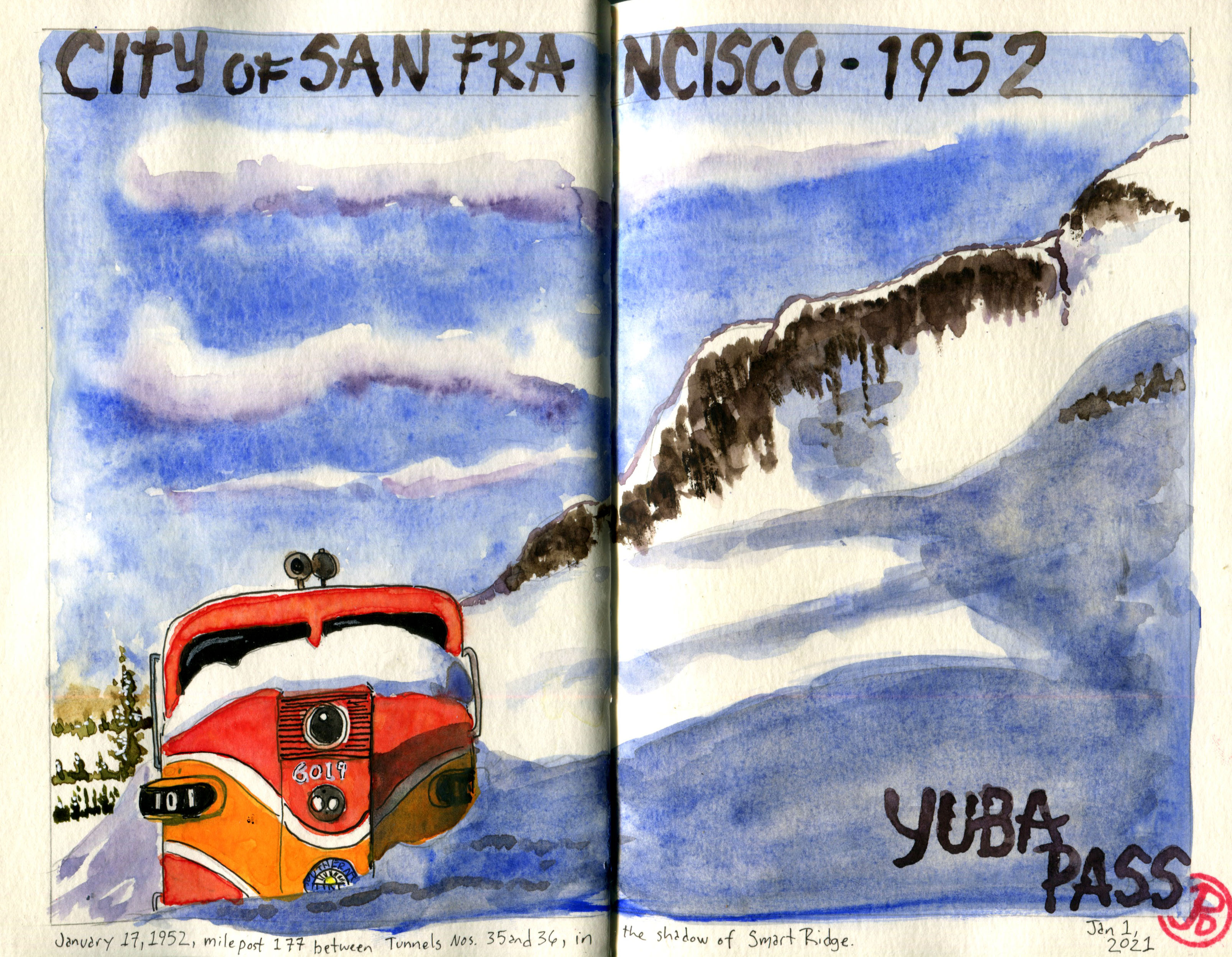

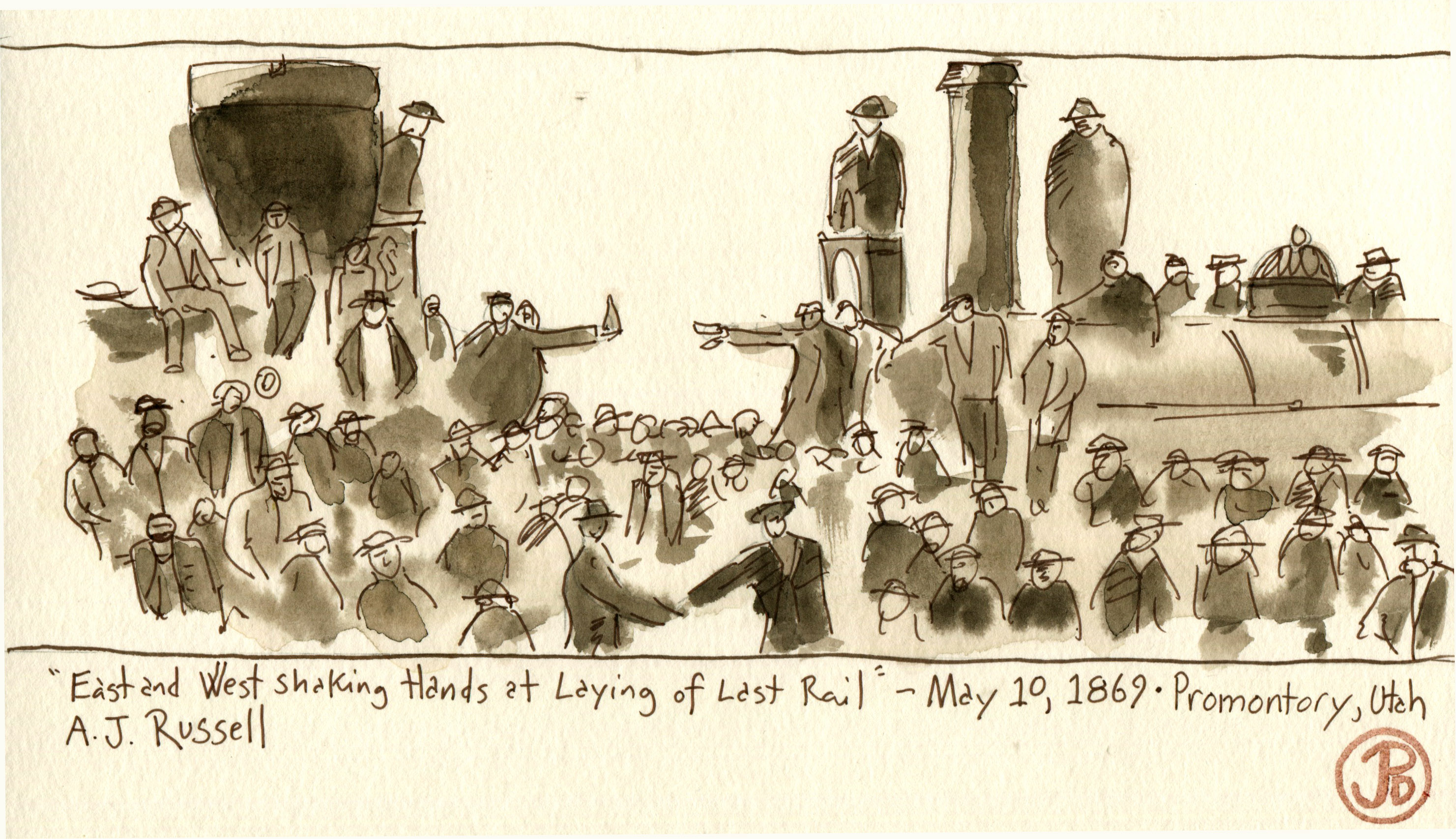

At this point I was on the route of the first Transcontinental Railroad. And I would need the strength of those who built it to face the reality, once I stepped off the Zephyr at one of the Central Pacific’s rail camps that was later renamed Colfax.

The anticipation mounted as we ascended down the western flank of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, each mile bringing me closer to my mother.

In past train journeys, one of my favorites scenes is when a train pulls into a station and looking out the window, I see someone alight from the train, search the platform for that familiar face, and then the embrace. I don’t always know the relationship contained in that embrace but it is a story on that reunion of love, in the the stage of the train depot.

What would the observer on the second story of the Superlunar have thought of the man departing the train and embracing someone, clearly his mother, in the middle of the street in Colfax?

I know what I would have though, and I did.