One SLO goal on my three day weekend visit was to summit Bishop Peak, and at 1,546 feet tall, it’s the tallest of the Nine Sisters.

The Nine Sisters, aka the Morros, are volcanic peaks stretching from Morro Bay to San Luis Obispo. Bishop Peak, named after the shape of the summit rocks, is a much sought after destination for hikers and climbers.

With forecasts for the day in the high 70s, I got an early start, hitting the trailhead at Highland Drive at 7:30 AM.

One change in my fairly recent hiking gear is trekking poles. I once ridiculed them as useless pieces of hiking chic. But as I grew older I now see them as an essential part of my hiking get up, so much so that I keep a pair in the trunk of my car at all times. They give me more points of contact, improve balance, and take pressure off the knees. And in a pinch I recommend they could fend off a mountain lion or bear. All of which is very necessary on the over 1,200 feet elevation gain thought uneven boulder terrain that is the Summit hike.

The first part of the hike led me to the base of the peak, past a cattle pond. At the top I could see a few hikers that had already summited. They must have gotten a much earlier start and hiked under headlamps. Cal Poly student no doubt.

I passed a climbing wall to my right and my climb to the peak really began in earnest when I reached the first of many switchbacks.

There was a dad with his two teenage sons who passed me. They had far less gear and no trekking poles!! I used them as a pacer, a reminder of my much slower pace, as I saw them on the switchbacks above mine. I would see their heads always moving forward above the chaparral. They were getting farther and farther ahead.

I soon started passing hikers coming down from the summit who had gone up to watch the sunrise. They had far less gear, water, and some were not even wearing hiking shoes. One group of girls had forgotten their headlamps so they had to use their phone light instead. Ah youth!

I was glad to have full sunlight and the views kept getting better and better the higher I climbed.

After hiking an hour, I could see the reddish rocks of the summit. The rocks that give the peak it’s name.

As I got closer to the summit there seemed to be a few false summits and the trail branched off in different directions, hemmed in by brush. One final scramble and I was greeted by a much appreciated bench. It was 8:35 and I had reached the top!

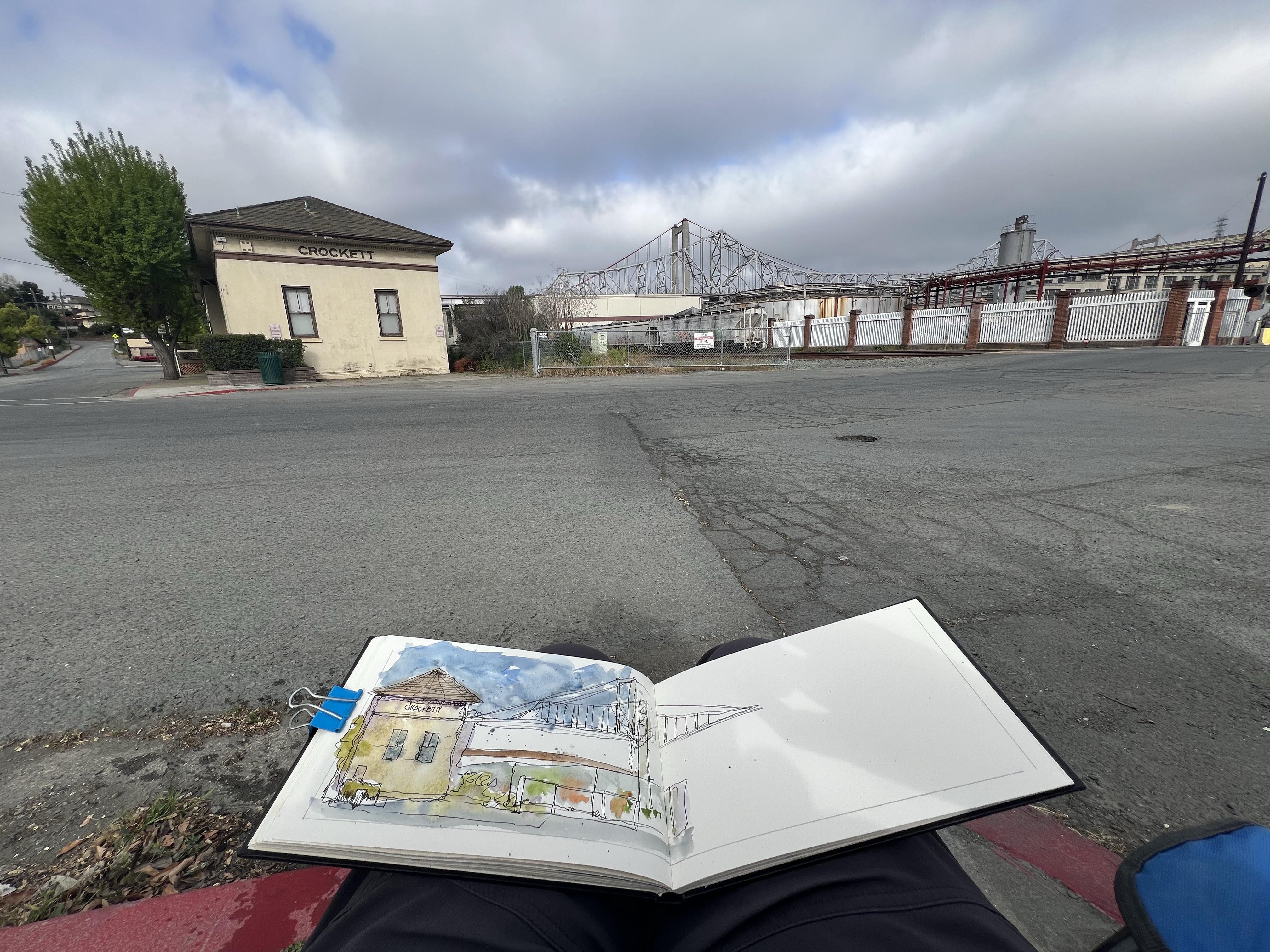

I drank some water, had some trail mix, and unpacked my panoramic sketchbook. It was sketch time.

After my sketch, it was time to descend, which I figured would be much easier than the climb up. It was five minutes to nine.

On my way down I passed about 30 people on their way up, including two large families with toddlers. The summit was soon to be one crowded place. Another great reason for an early start.

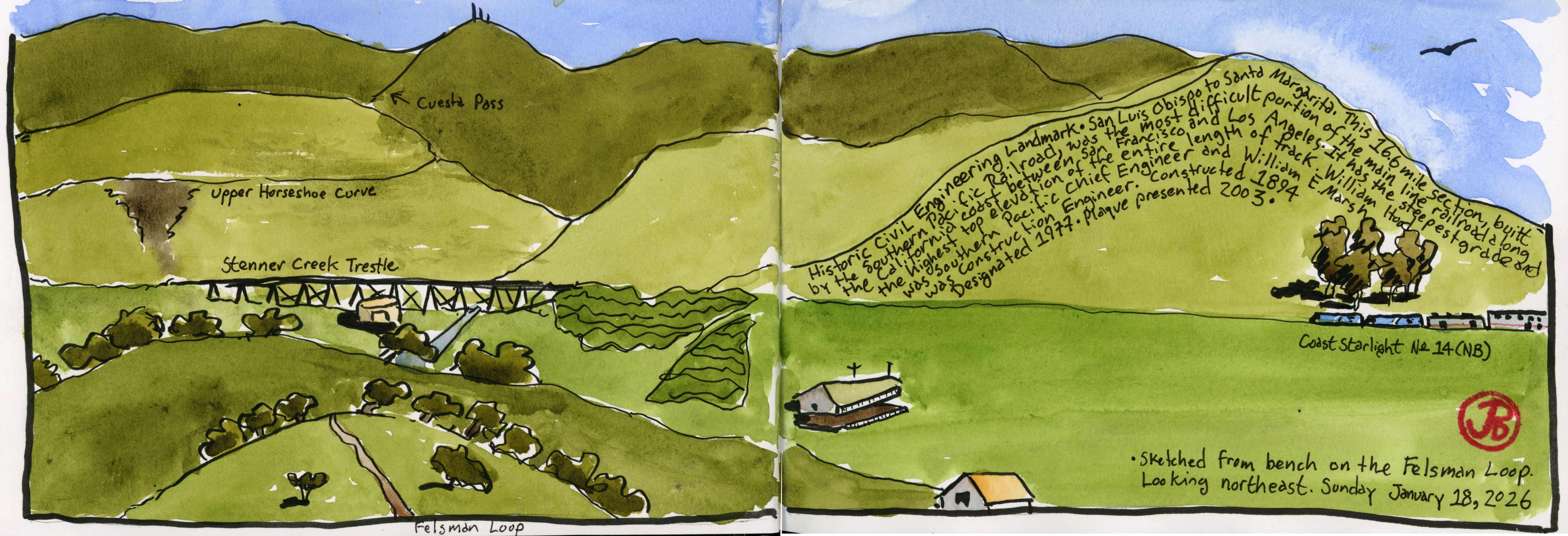

At the end of my descent, I turned left at the cattle pond and walked out on the Felsman Loop Trail toward a sketching bench.

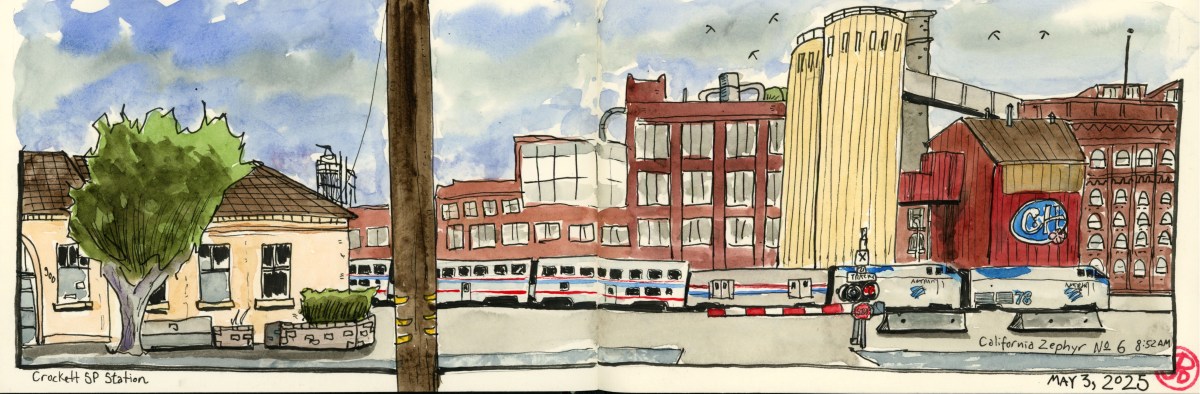

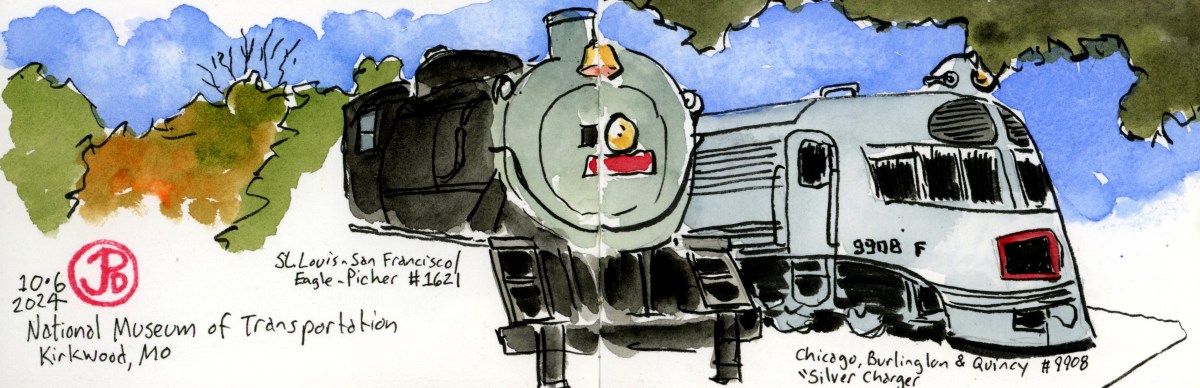

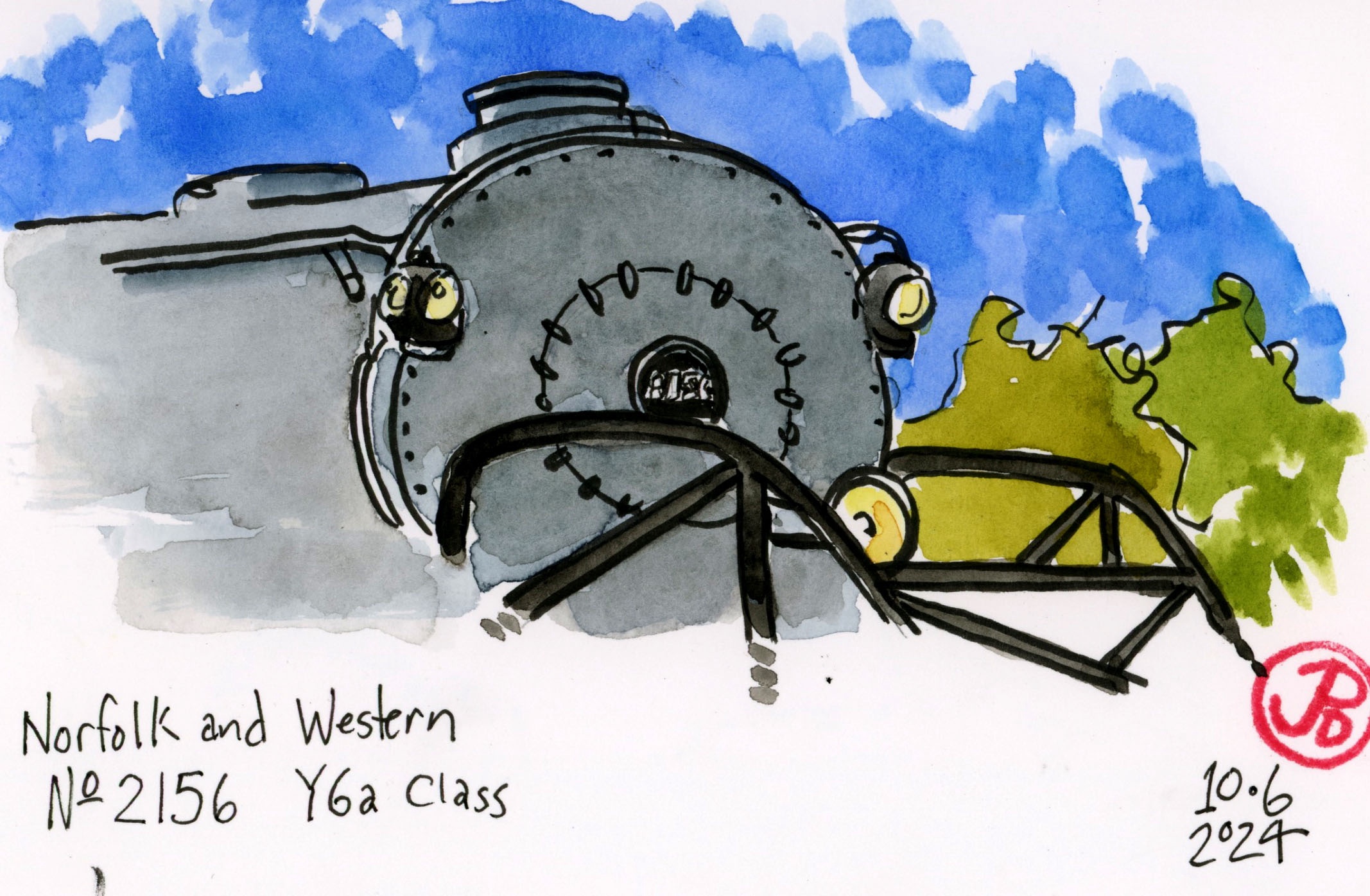

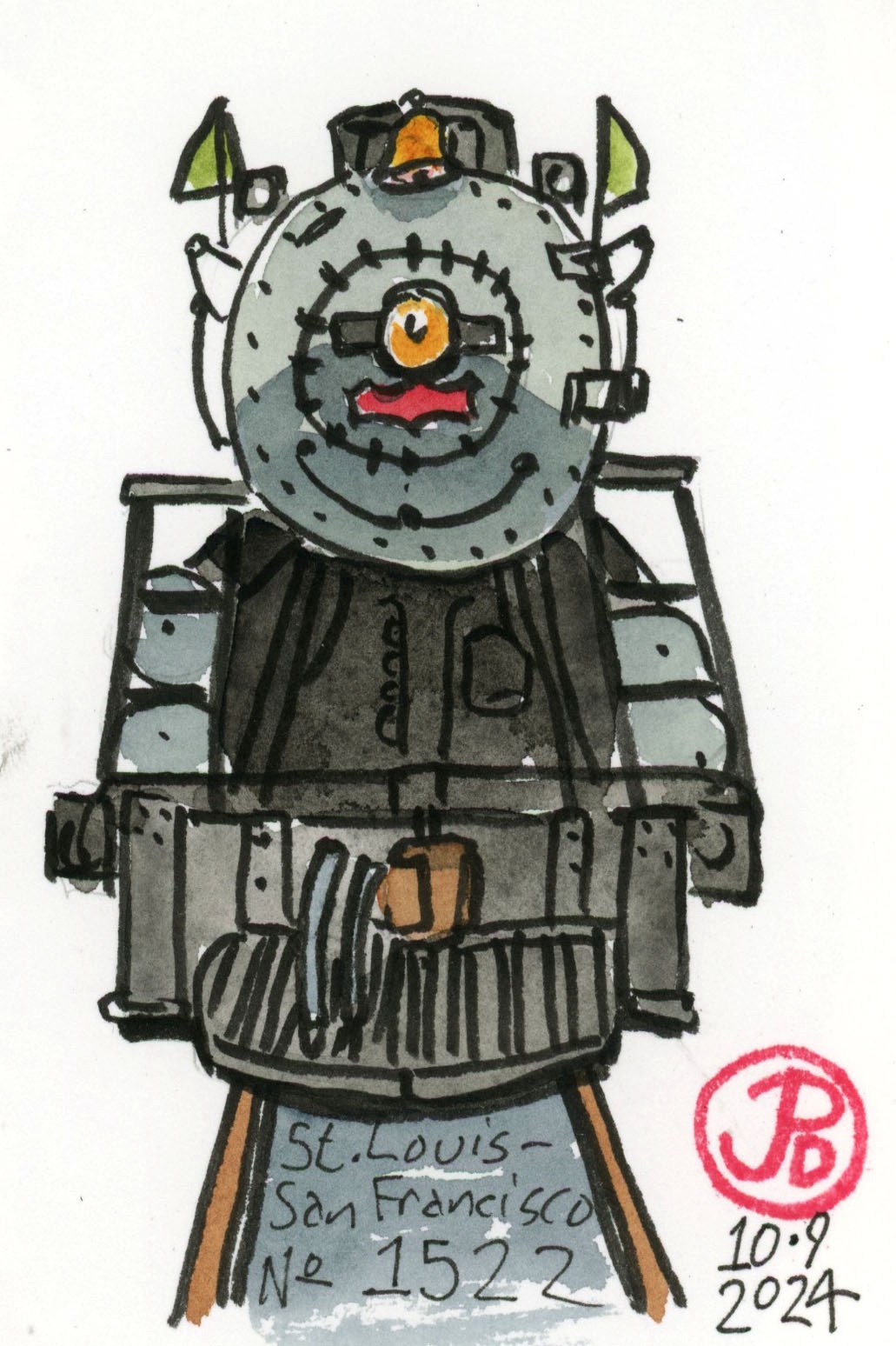

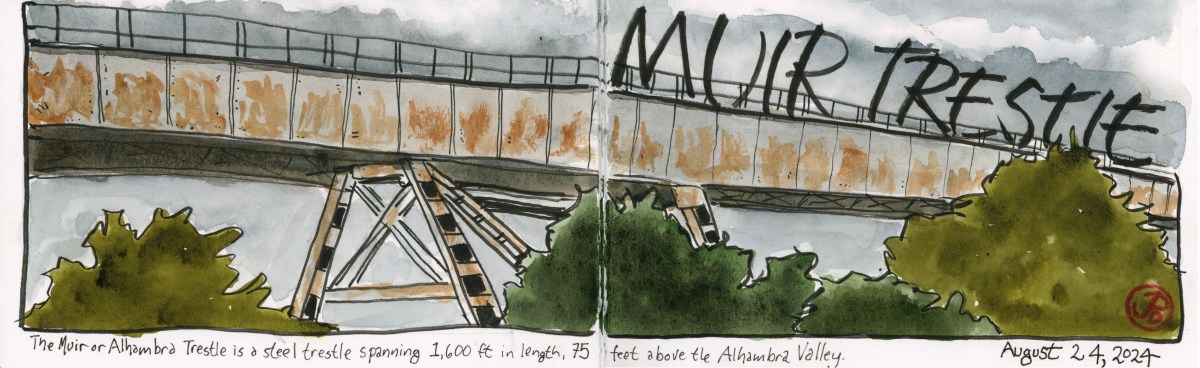

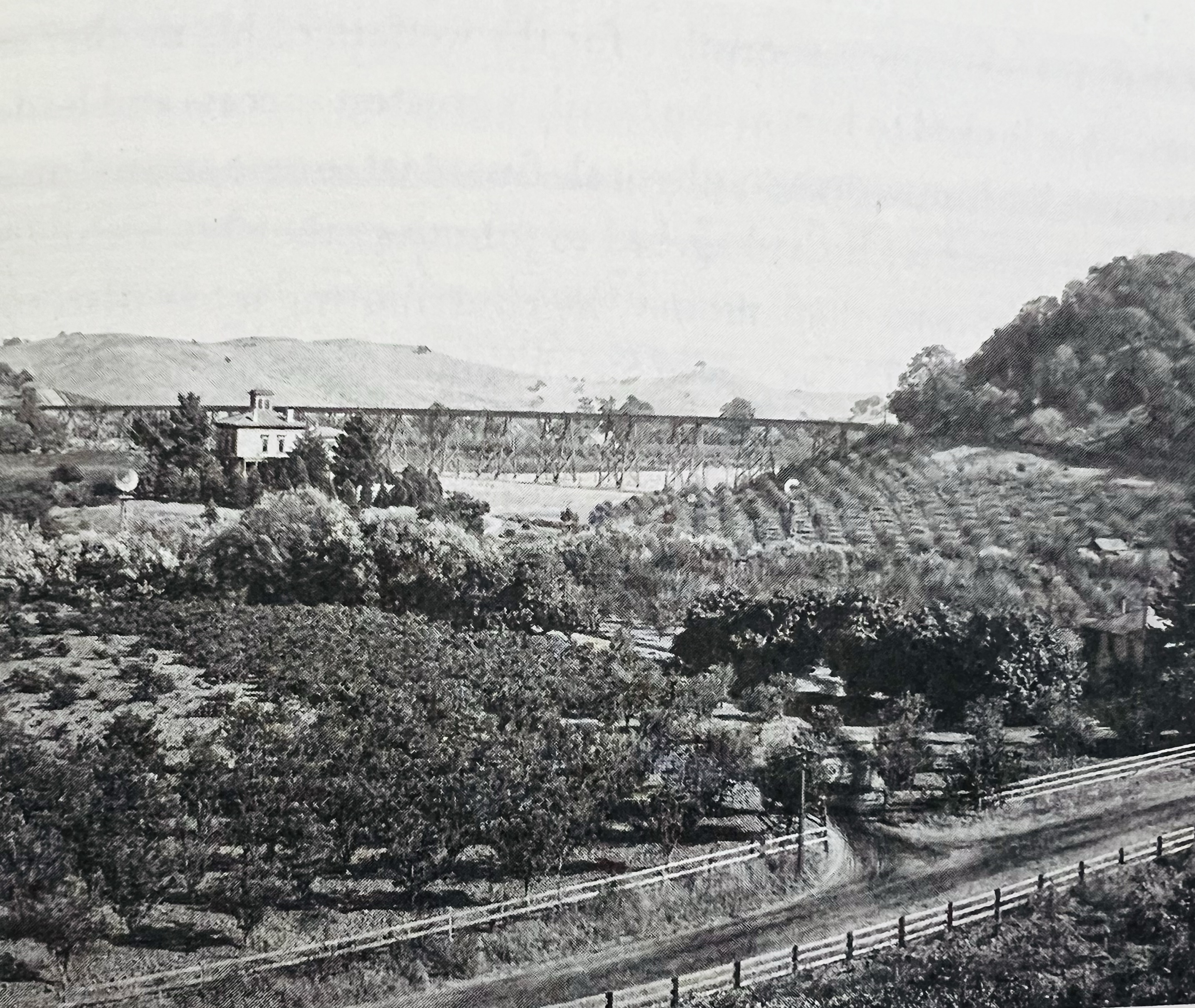

The view before me was an acknowledged Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, the 16.6 mile portion of railroad that climbs the Cuesta Grade and the series of tunnels near the summit. From my vantage point, Stenner Creek Trestle was before me and the line snakes around in the famous Horseshoe Curve.

I sketched the beautiful green Californian curvaceous hills. This was a great time to be here!