The AMTRAK route that parallels the west coast from Los Angeles to Seattle is the Coast Starlight, a journey of 1,377 miles.

In those 1,377 miles the only place that both the northbound and southbound (Trains 14 and 11) meet at a station is San Luis Obispo.

Northbound 14 arrives from Los Angeles at 2:50 PM (if on time) and waits for southbound train 11 (due at 3:24) to descend the single track down Cuesta Grade. And I planned to be there to do some sketching.

My plan was to sketch the northbound Train 14 at SLO station. In the age of steam, the Coast Daylight (SF to LA) stopped for only three minutes at San Luis Obispo in order to keep to its timetable.

During this short stop the Southern Pacific GS (Golden State or General Service) steam locomotives would be serviced and tender topped off with water. A helper locomotive would either be cut in or cut off depending on the direction of the Daylight.

Now the AMTRAK train would stop for about 15 minutes, allowing passengers a stretch break, for some passengers this is also known as a smoke break.

I figured 15 minutes was more than enough time to get a quick sketch in of the train at the platform before the locomotive’s loud retort announced its continued journey up the Cuesta Grade towards Seattle.

I took up my sketching position a little before the Starlight’s arrival. I penciled in the foreground and the trees in the background, not knowing which trees would be eclipsed by the double decker Superliner cars. The answer was: most of them.

When the train pulled into the station, I switched to pen. I love sketching without a net!

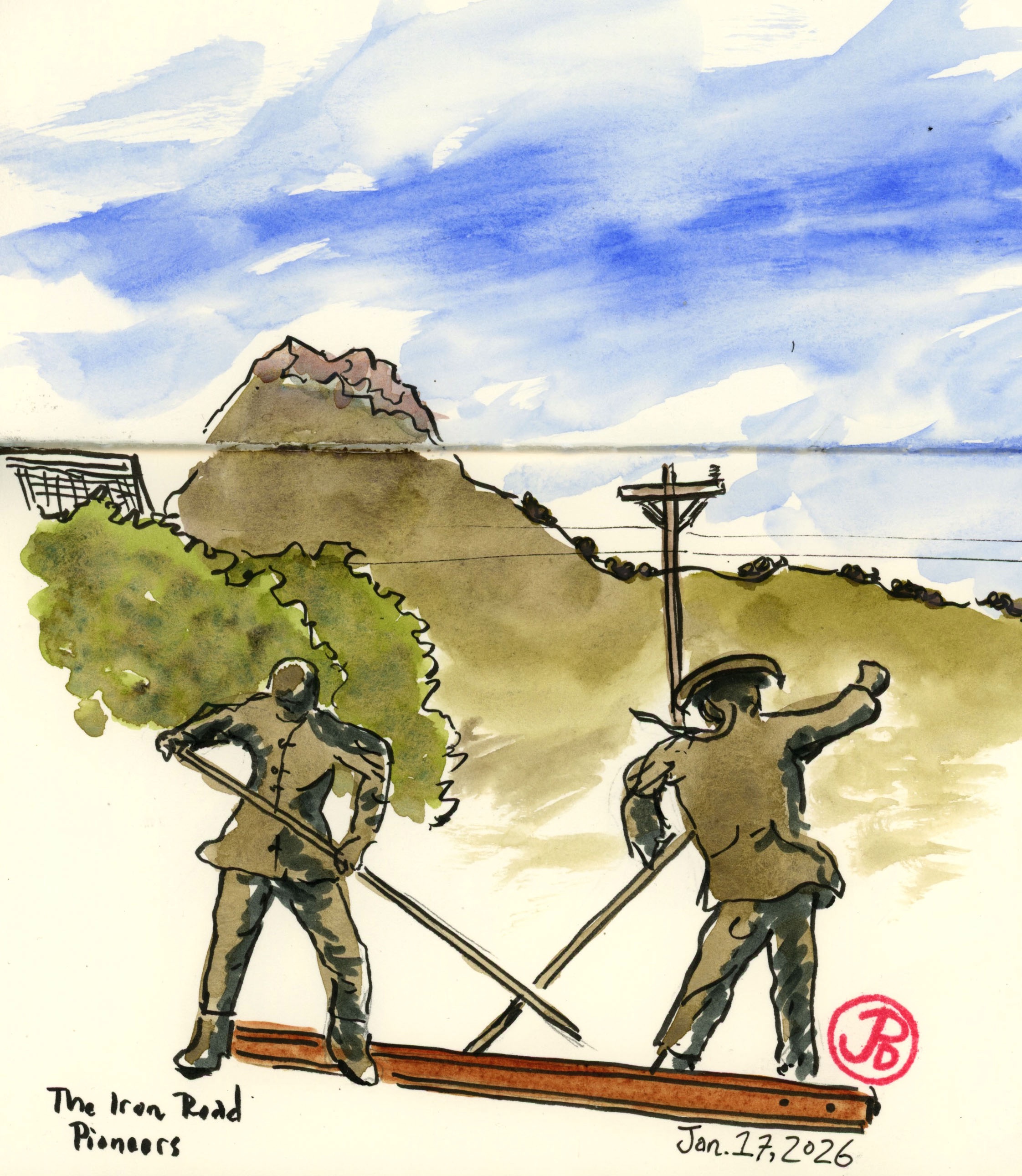

While waiting for the northbound Coast Starlight, I found a bench and sketched the statues near the station called the Iron Road Pioneers, with Bishop Peak in the background.

The statues are a monument to the Chinese immigrant workers who built much of the railroads on the central coast as well as other seminal railroads such as the Transcontinental Railroad.