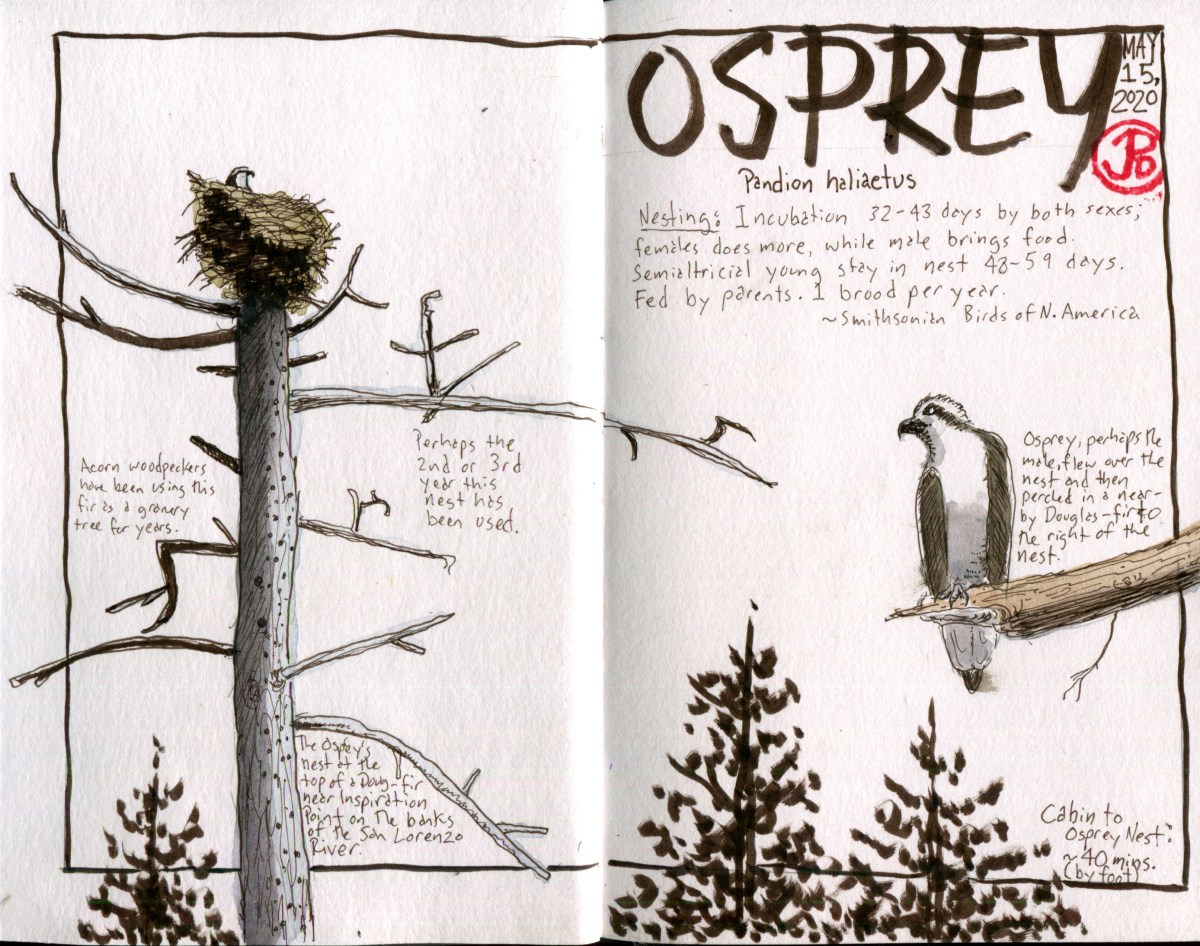

One of my neighbors knew I was struck with the affliction of birding and told me about the osprey’s nest on top of a Douglas-fir along the railroad about a 30 minute hike up river from my cabin.

After work on Friday, I hiked out of Paradise Park via the fire road and scrambled up a deer trail to the even grade of the railroad. This railroad is now operated by the Santa Cruz, Big Trees and Pacific Railway and takes tourists from Felton to Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk. At one time the railroad went over the Santa Cruz Mountains to Los Gatos but now does not go very far beyond Felton. I have hiked this railroad since my youth and it had been a few years since I played hopscotch on railway ties up the San Lorenzo Valley.

Walking along this rustic railroad always feels like I’m participating in a scene from Stand By Me on a quest to find a dead body. But in this case I was in search of a big bunch of sticks on top of a fir, high above the San Lorenzo River.

I kept one eye on the rails and one on the trees off to my right. My neighbor had given me good directions to the nest and when I was 30 minutes out of Paradise, I thought that maybe I had passed the nest. But how could I miss it? So I continued hiking upstream.

Ten minutes later the osprey nest appeared across the river between a break in the redwoods and firs. I put bins on the nest and could not detect any occupants. But osprey nests are deep and the osprey could be laying low. The only sign of life were the acorn woodpeckers that looked to have used the fir as their granary tree, their acorn larder, for years.

I was at a point in the line where the railroad curves gracefully over a curved viaduct. The concrete arched bridge was build by the Southern Pacific Railroad in March of 1905 and spans Coon Gulch. At this point the San Lorenzo River takes a turn and you can get an amazing view upstream. This point in the line is known as Inspiration Point.

It didn’t take long to see signs of life. An osprey flew in and briefly alighted on the nest. Bingo! The nest is occupied after all. The unseen osprey, presumedly sitting on eggs, sat up in the nest and became visable.

The osprey that flew in could have been the male who is responsible for bringing fish to the nest while the female does most of the incubating of the two to three eggs. The male perched near the nest on a Doug-fir and preened.

I stood by the railside and sketched the nest. On the left side of the spread is my field sketch (first in pencil then in dark sepia pen) of the Douglas-fir crowned by the osprey nest. The osprey perched on the right was drawn from a field photo I took of the presumed male. The title and text were added back at the cabin. In the end, I decided to create a spread that is almost monochromatic. I resisted the urge to paint in the sky because I didn’t want anything to distract from the form of the Doug-fir and nest.

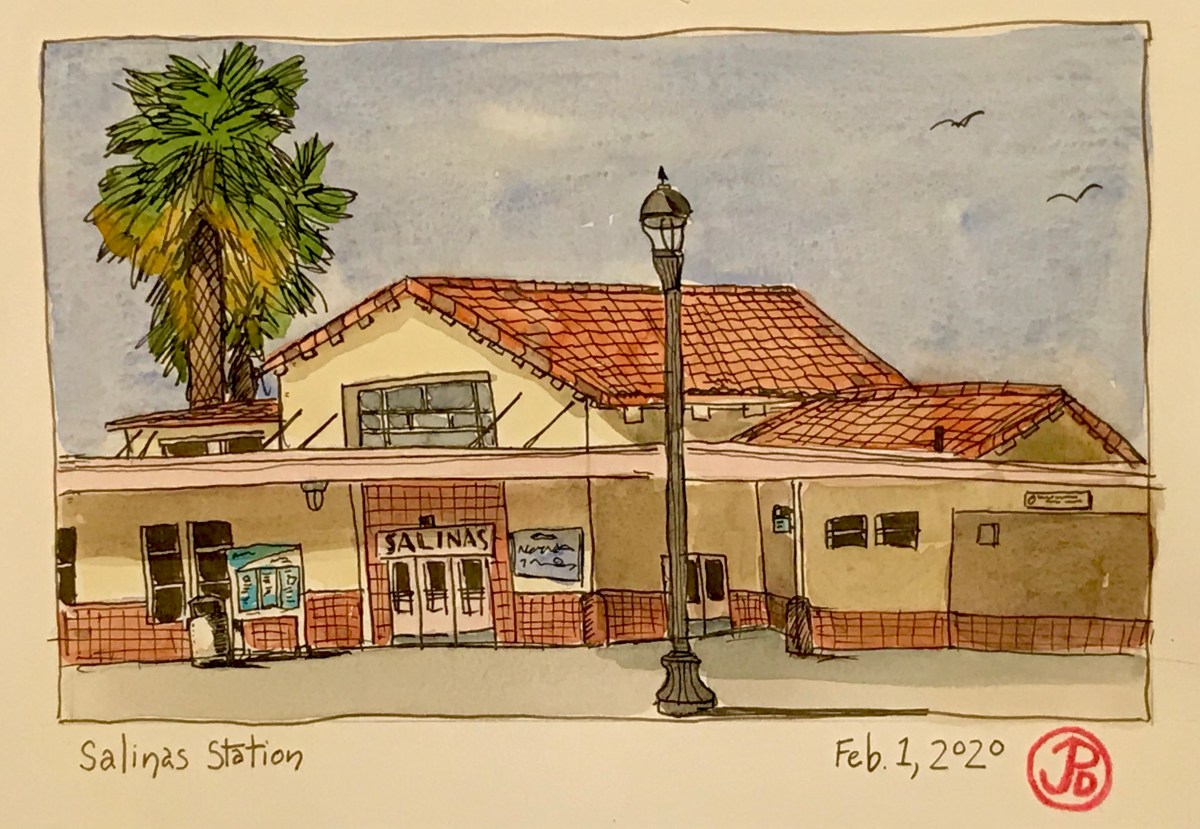

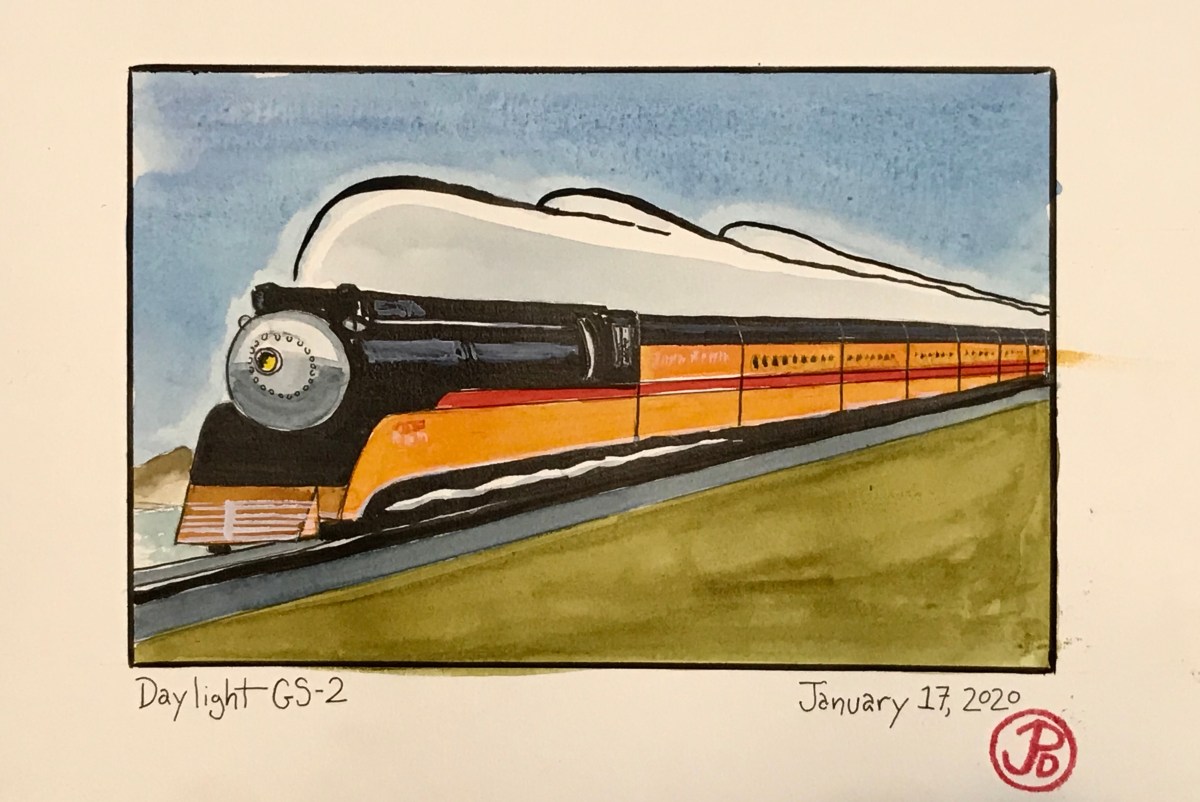

The John MacQuarrie mural at Salinas was painted in 1941 (the same year as the Palo Alto mural) and prominently features the star motive power at the time, the Golden State 2 (GS-2). Six of these locomotives were built and went into service in 1937.

The John MacQuarrie mural at Salinas was painted in 1941 (the same year as the Palo Alto mural) and prominently features the star motive power at the time, the Golden State 2 (GS-2). Six of these locomotives were built and went into service in 1937.

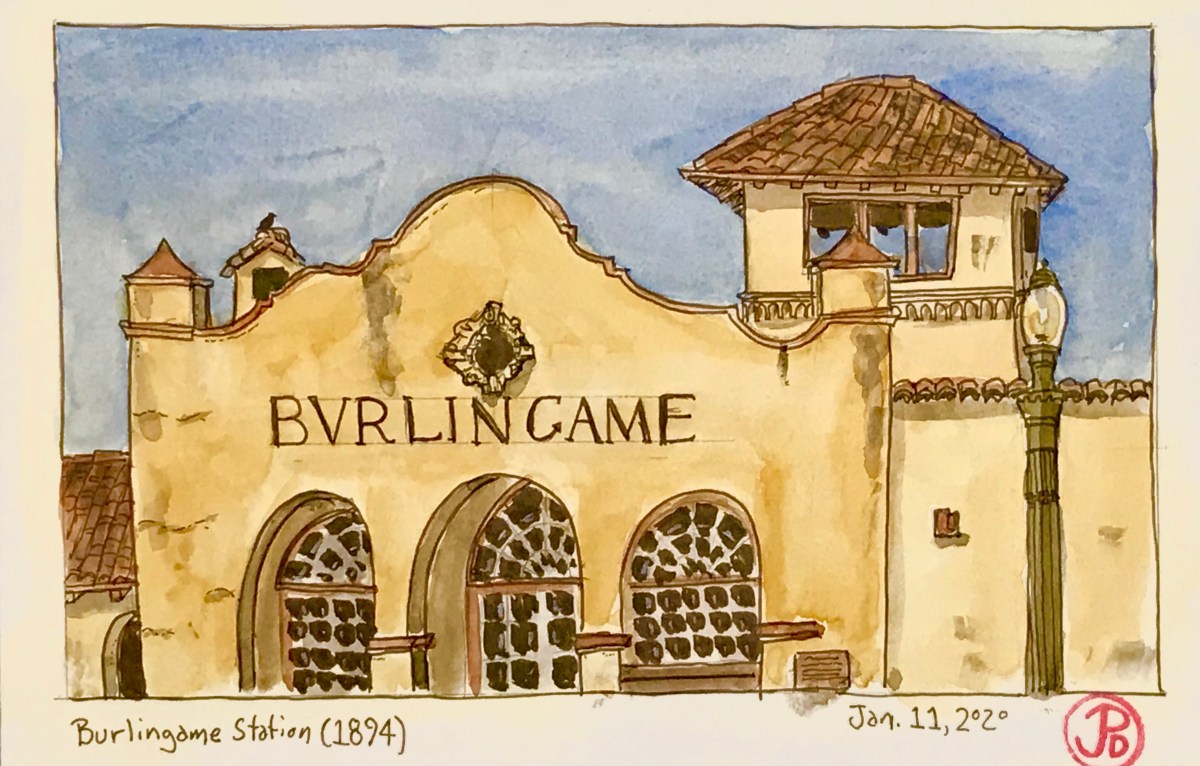

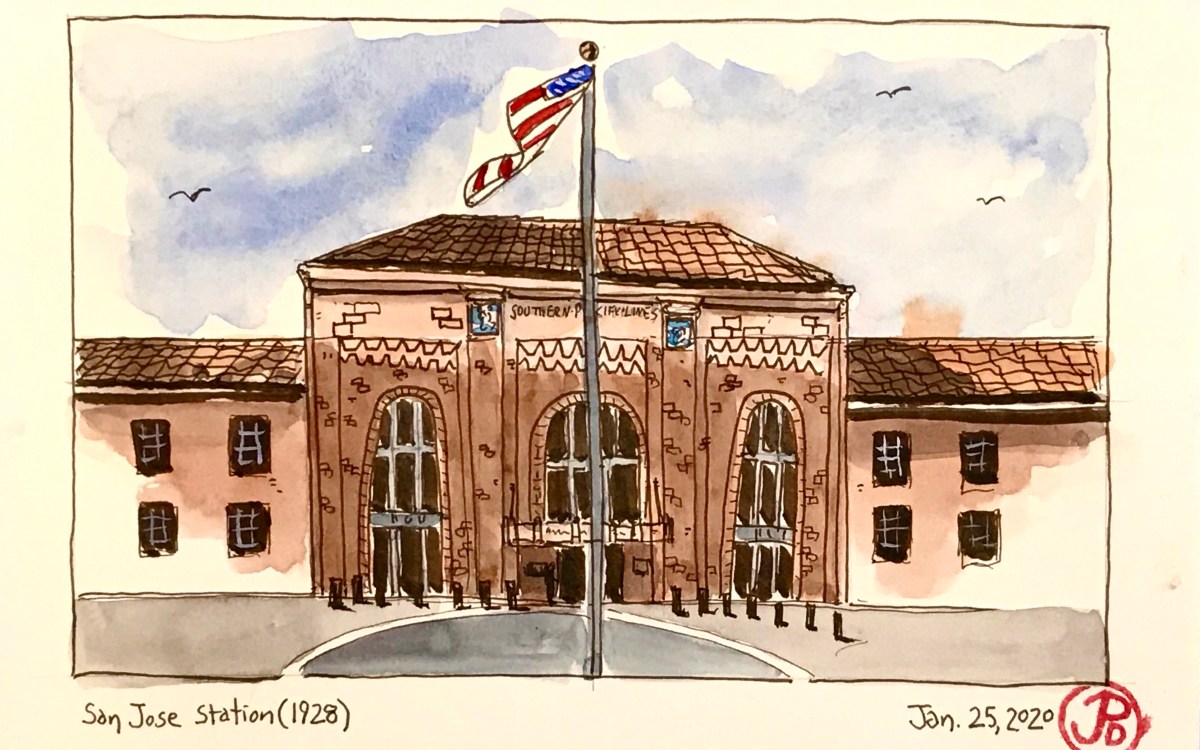

The passenger depot in January of 2020, looks in great shape compared to other historic depots I have sketched on the line. This is due to the hard work of the volunteer labor of the South Bay Historical Railroad Society.

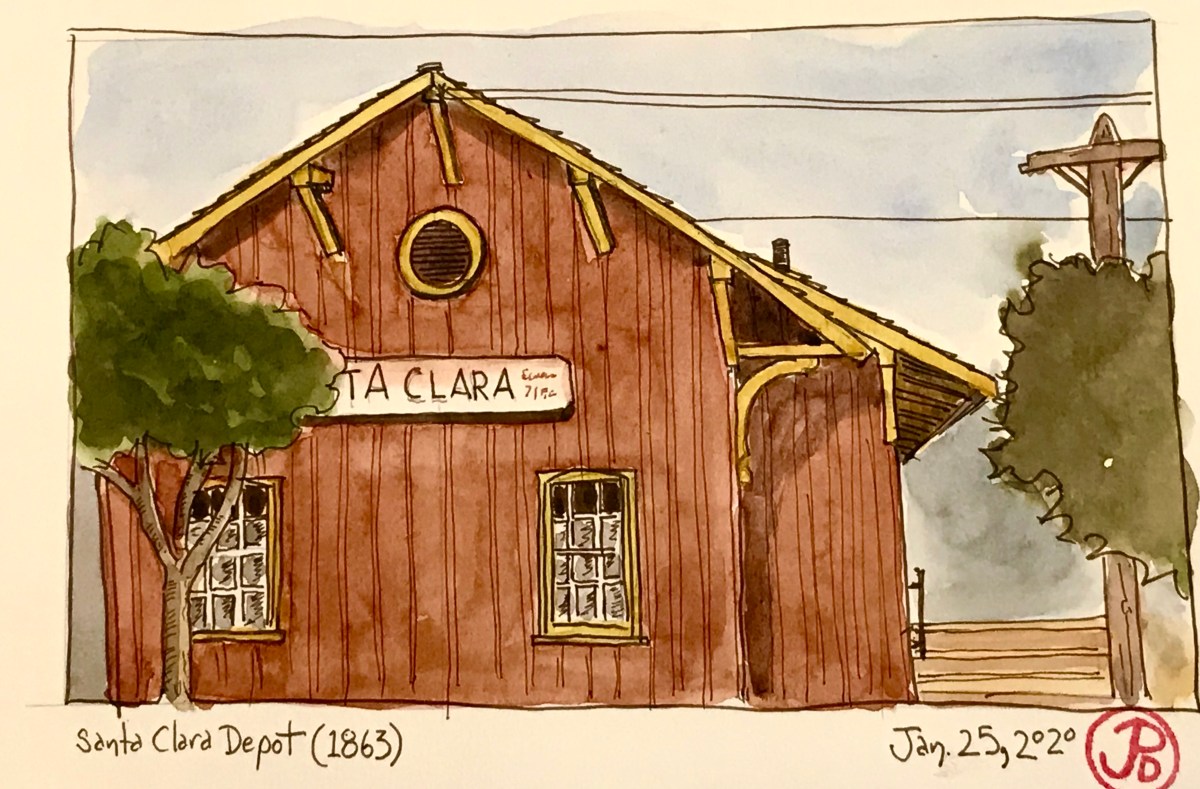

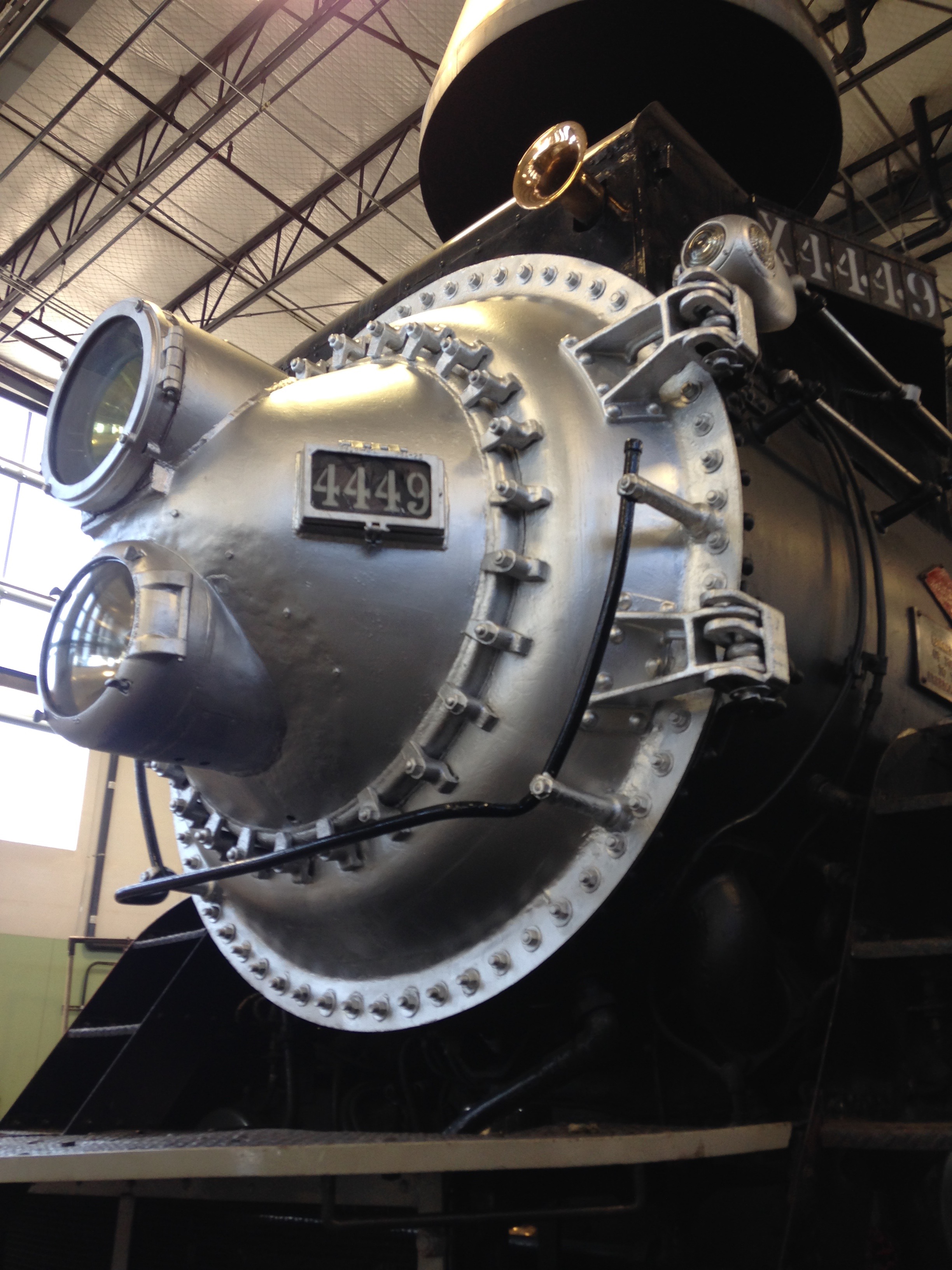

The passenger depot in January of 2020, looks in great shape compared to other historic depots I have sketched on the line. This is due to the hard work of the volunteer labor of the South Bay Historical Railroad Society.  One of the few places you can still see Southern Pacific in action, although in HO scale, is at the South Bay Historical Railroad Society. I had a model railroad when I was a kid. My HO gauge railway ran in an oval with a small town in the center. I had a Santa Fe “Super Chief” locomotive but my favorite was a Daylight GS-4 number 4449. The full scale locomotive pulled its passenger consist past Santa Clara Station but did not stop. Passengers wishing to board the Daylight had to go to San Jose.

One of the few places you can still see Southern Pacific in action, although in HO scale, is at the South Bay Historical Railroad Society. I had a model railroad when I was a kid. My HO gauge railway ran in an oval with a small town in the center. I had a Santa Fe “Super Chief” locomotive but my favorite was a Daylight GS-4 number 4449. The full scale locomotive pulled its passenger consist past Santa Clara Station but did not stop. Passengers wishing to board the Daylight had to go to San Jose. This an original bench in the passenger waiting room of Santa Clara Station.

This an original bench in the passenger waiting room of Santa Clara Station. This control tower was built in 1926 and was in continuous use until July 17, 1993. The tower was built at the junction of Southern Pacific’s Coast and Western Divisions.

This control tower was built in 1926 and was in continuous use until July 17, 1993. The tower was built at the junction of Southern Pacific’s Coast and Western Divisions.

The mural stretches above the wall where the ticket counter is. It depicts the past and future of transportation. A stream of men on horses, Indians with travois, wagons, stage coach, and men and women walking on foot, head to the right with the quad of Stanford University in the background. In the lower left corner the profile of Leland Stanford looks on towards the future of transportation (circa 1940). The future seems to come out from behind the trees as a Daylight GS-3 locomotive proclaims it’s entrance into the mural. This certainly a synthesis between a beautiful and functional form of transportation and a building that does the same.

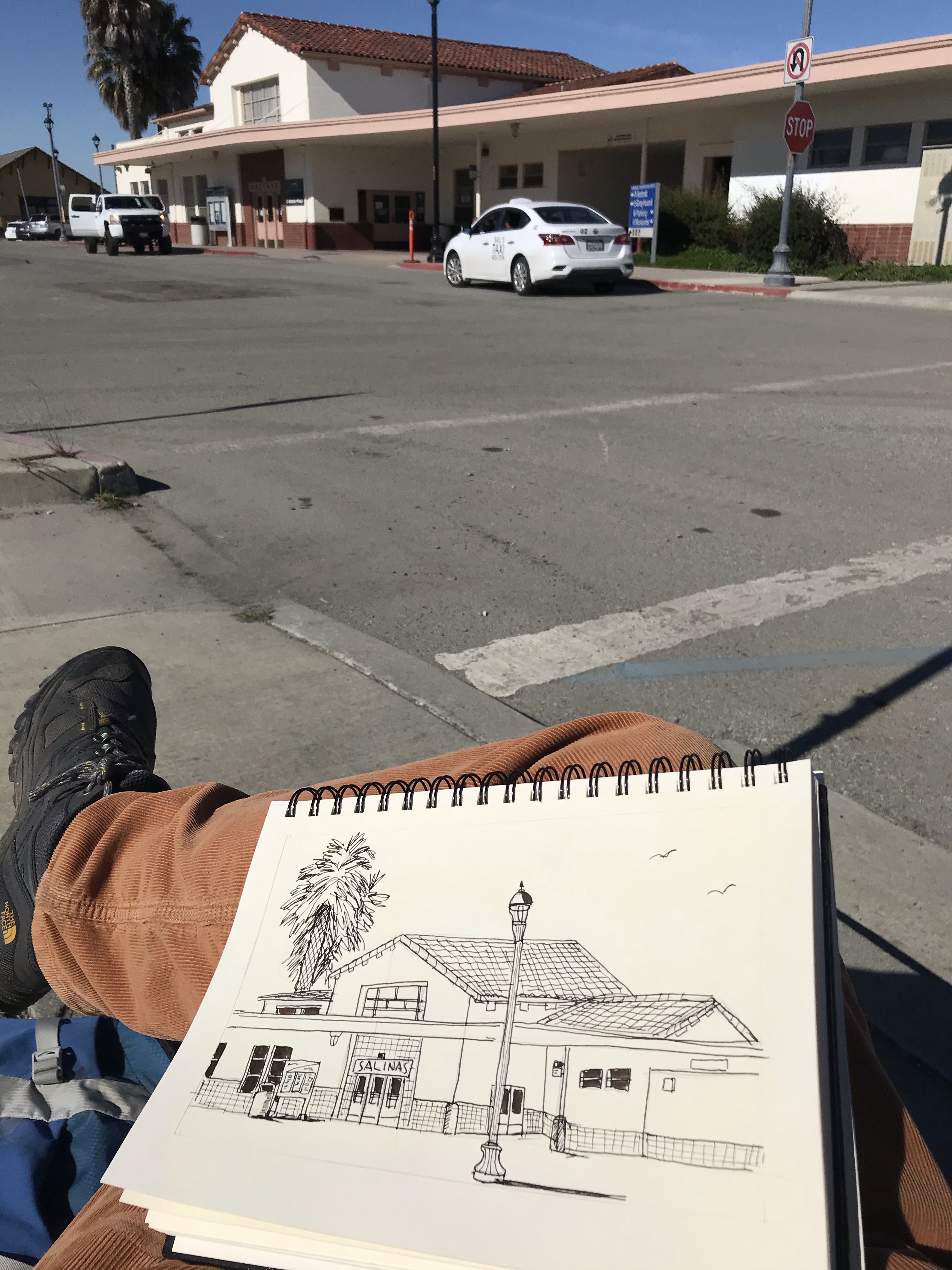

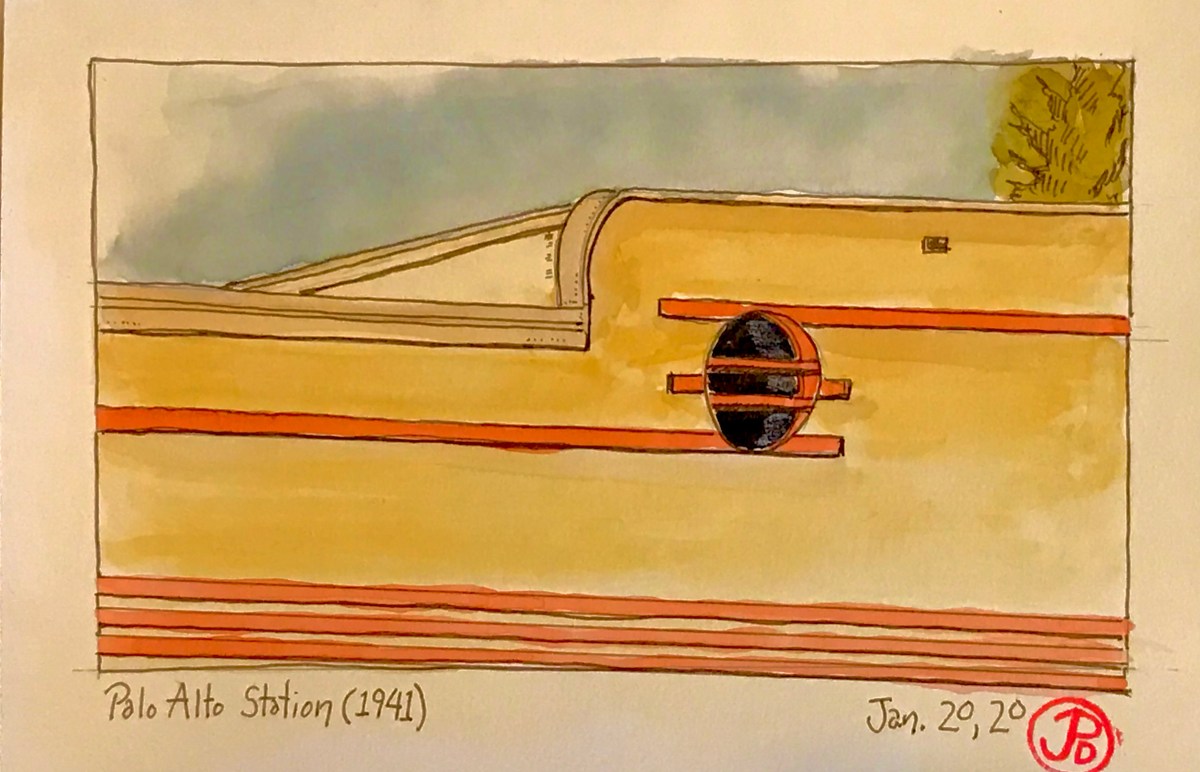

The mural stretches above the wall where the ticket counter is. It depicts the past and future of transportation. A stream of men on horses, Indians with travois, wagons, stage coach, and men and women walking on foot, head to the right with the quad of Stanford University in the background. In the lower left corner the profile of Leland Stanford looks on towards the future of transportation (circa 1940). The future seems to come out from behind the trees as a Daylight GS-3 locomotive proclaims it’s entrance into the mural. This certainly a synthesis between a beautiful and functional form of transportation and a building that does the same. Here is my quick sketch of Caltrain’s most “modern” historic station. I left details out, like the door into the station. I was really trying to get the shapes of the building.

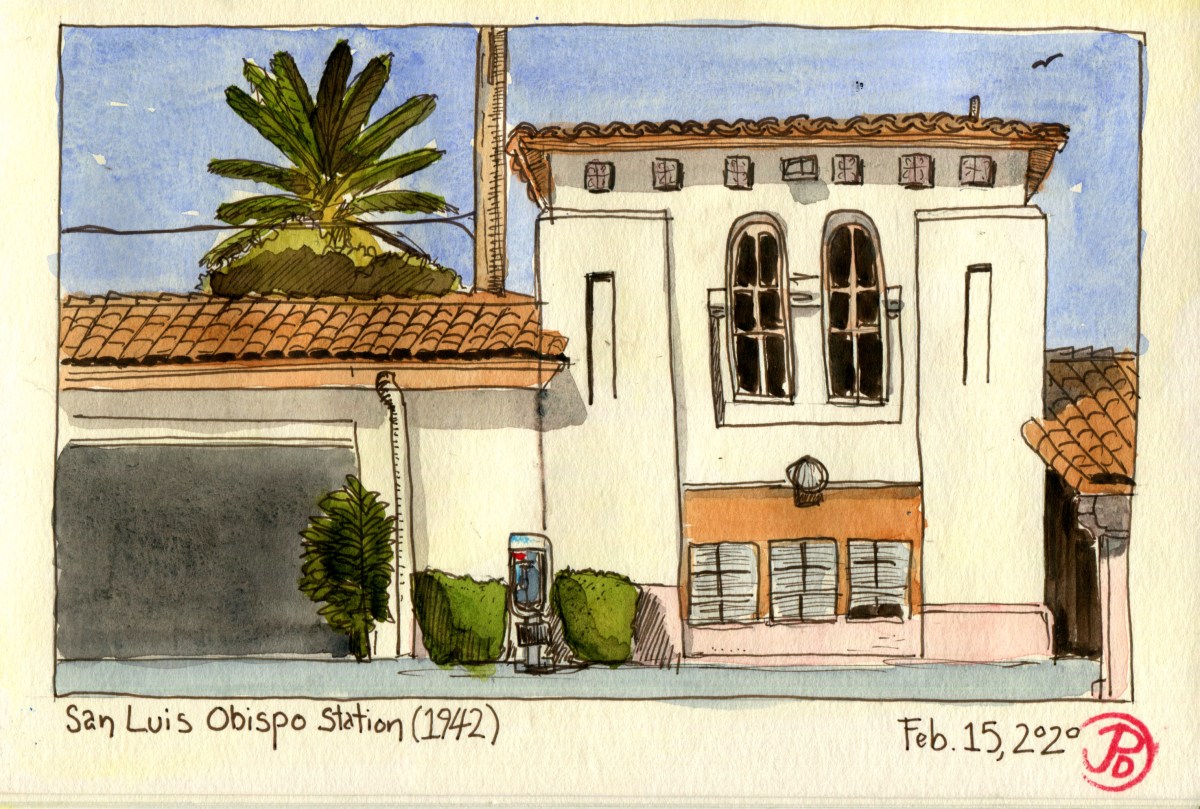

Here is my quick sketch of Caltrain’s most “modern” historic station. I left details out, like the door into the station. I was really trying to get the shapes of the building.

A field sketch of the “Queen of Steam”, GS-4 locomotive number 4449 in Portland, Oregon. This is the only operational engine still in existence that worked the Daylight route.

A field sketch of the “Queen of Steam”, GS-4 locomotive number 4449 in Portland, Oregon. This is the only operational engine still in existence that worked the Daylight route.

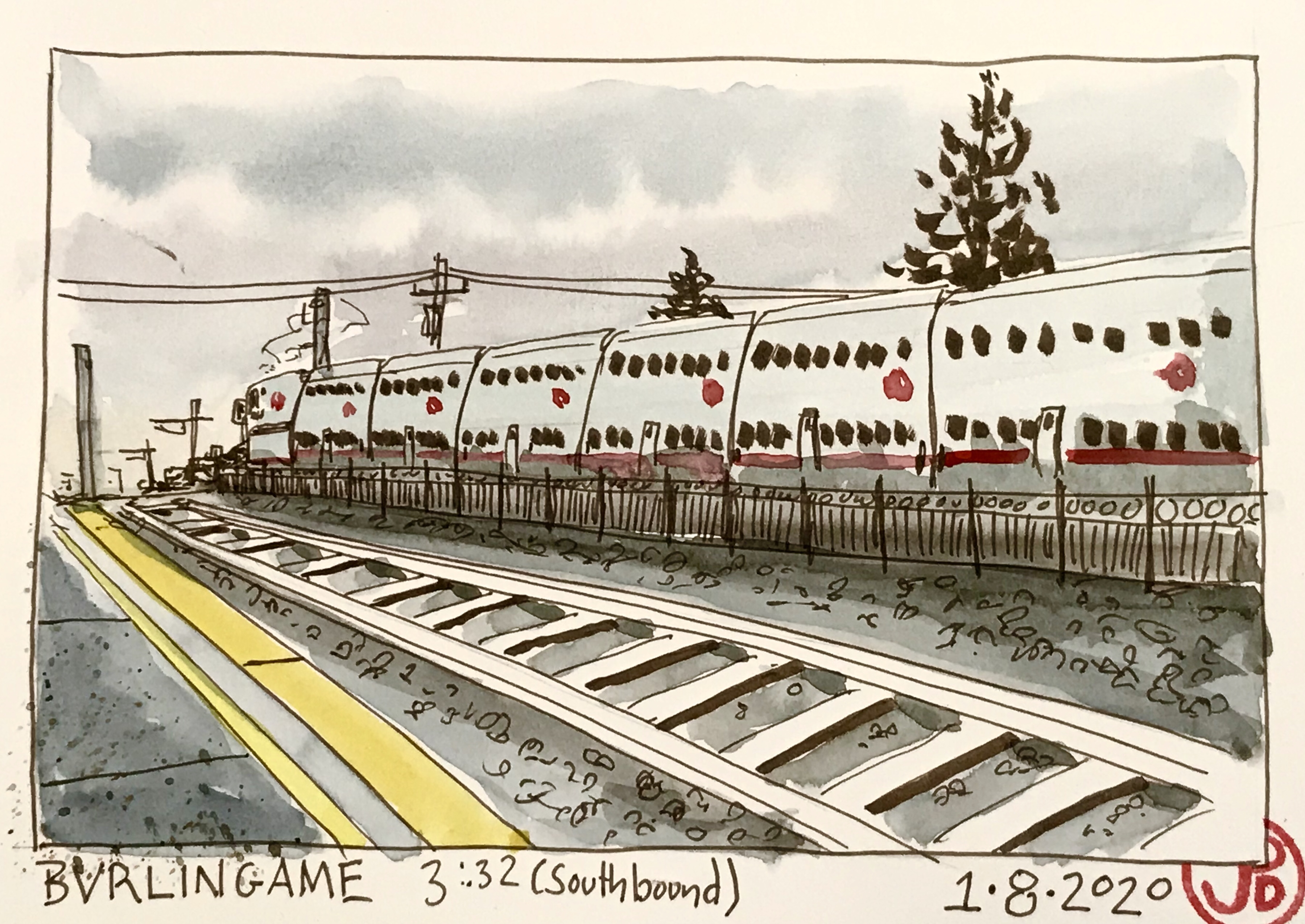

Engine Number 905 “Sunnyvale ” is on the point of a southbound train to San Jose. This engine is named after my hometown.

Engine Number 905 “Sunnyvale ” is on the point of a southbound train to San Jose. This engine is named after my hometown. The train station at Sunnyvale is long gone. I never remember it as being an amazing piece of Southern Pacific architecture. The station has been replaced with a ticket shelter that connected to a parking shelter.

The train station at Sunnyvale is long gone. I never remember it as being an amazing piece of Southern Pacific architecture. The station has been replaced with a ticket shelter that connected to a parking shelter.