I was meeting a friend in the East Bay city of Martinez and I had a little time to sketch before lunch.

Martinez is a hotbed of railroading with both the Union Pacific and BNSF passing through as well as some marquee passenger trains such as the Coast Starlight and the California Zephyr making stops at the Martinez AMTRAK station. And the Capitol Corridor commuter takes on passengers traveling north and south on shorter journeys.

There would certainly be something to sketch here and I was going to start with a historic train trestle.

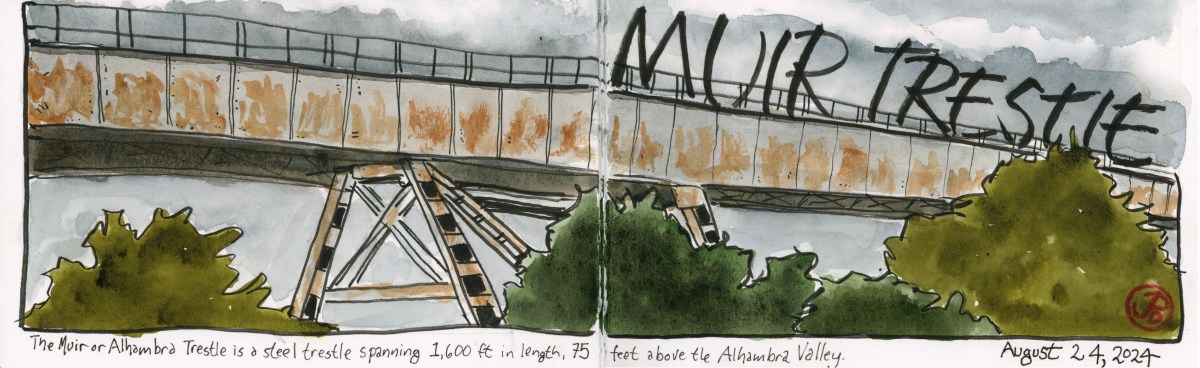

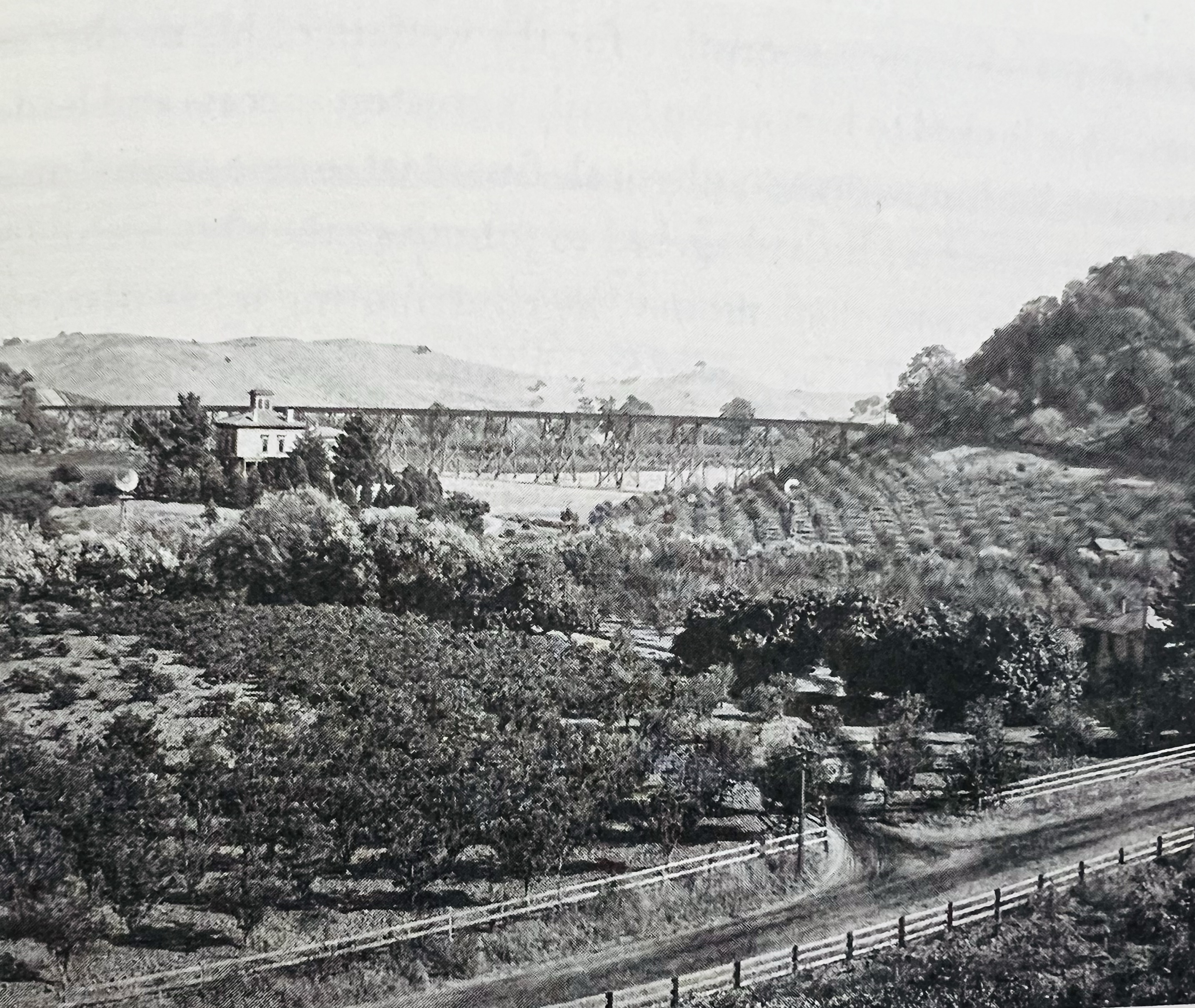

I parked at the Mount Walda Trailhead. Soaring above me was the 1,600 foot long steel Muir Trestle (aka the Alhambra Trestle). The single track trestle was so long that I could only see and sketch one section of it before it disappeared into the trees to the east. The trestle rises 75 feet above the roads, trees, and houses it crosses over.

The trestle is within the John Muir National Historic Site. To the north is Muir’s Martinez home. Muir and his wife Wanda sold the land for the trestle for $10 and a lifetime rail pass to the San Francisco and San Joaquin Valley Railway. The original wooden trestle was built through a pear orchard and completed in 1897.

At the eastern end of the trestle there was a passenger and freight station named Muir Station. The station is now long gone but is immortalized in a street that parallels the rails named Muir Station Road.

From this station Muir could ship his produce to Oakland or to the port in Martinez.

One of Muir’s neighbors in the Alhambra Valley was John Swett, Muir close friend. Swett was the State Superintendent of Public Education and is known as the “Father of California Public School”.

In 1898, Santa Fe purchased the line and it became their Valley Division. This division still exists as BNSF’s route from Richmond to Fresno.

I took up a sketching position near the trailhead and started my drawing. The trestle above me is on the Stockton subdivision and is used by BNSF intermodal freight. There was no train crossing during my sketch.